Armand’s testimony of his experiences during WW II as a 15-year-old in Menilmontant, Paris, is recorded in a video interview for the Museum of Jewish Heritage. His mother, Ita, and young brother, Robert, aged eight, perished in Auschwitz-Birkenau. His father, Max, older brother Daniel, and Armand survived by hiding in a secret room inside their apartment, devised by Max.

The following accounts are drawn from Armand’s testimony. You can view the full interview live on YouTube (search on YouTube for “Armand Handfus, Holocaust Survivor”).

Armand was born in Paris at the Rue de Santerre hospital. He lived with his family at 17 Rue Henri Chevreau in the 20th Arrondissement, a working-class immigrant neighborhood.

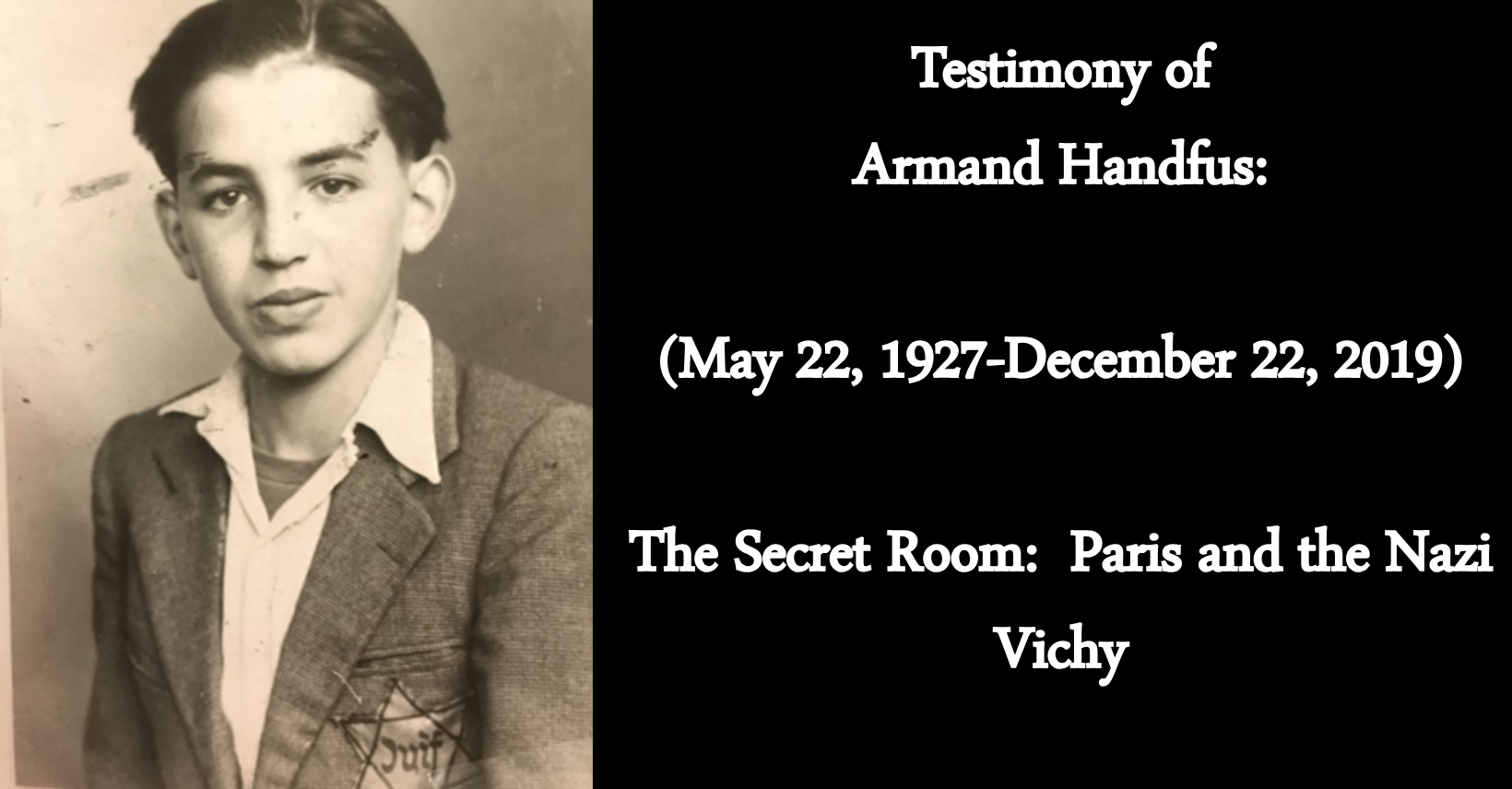

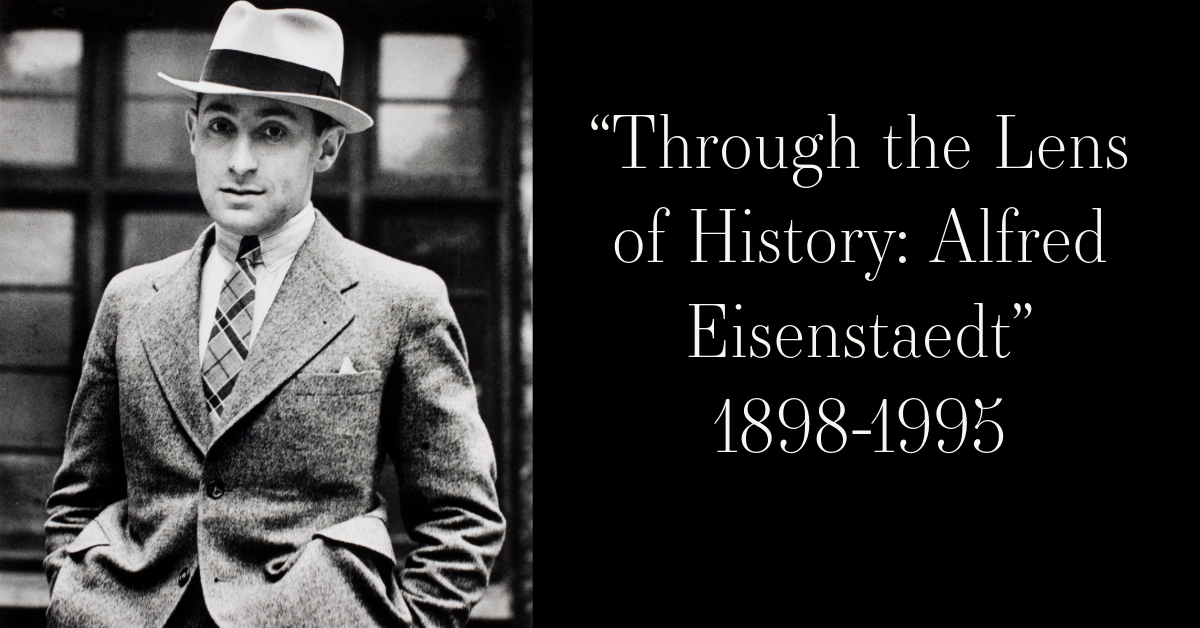

Armand, age 15, during Occupation of Paris

Menilmontant was, in Armand’s recollection an integrated working-class neighborhood where Jews and non-Jews lived and worked together. Jewish life was active and robust. Daniel, Armand’s older brother, celebrated his Bar Mitzvah, youngest child Robert’s bris was a happy gathering of friends for cake and coffee. Armand, his Hebrew studies interrupted by the war, would in 2007 be Bar Mitzvah at age 80! (Photos of the occasion are in the Permanent Collection of the Museum of Jewish Heritage.)

Parents Max and Ita, newly arrived immigrants from Warsaw, Poland, in 1925 settled at first with infant son Daniel, in a single room in Menilmontant. Armand was born two years later, in 1927, and in 1934 with the advent of the birth of young Robert, they were forced by necessity to expand the family’s living quarters.

This decision, in the early 1930’s to expand the apartment would prove crucial in the survival of three family members.

By the late 1930s, antisemitism became widespread and virulent.

In Armand’s words:

“…Antisemitism was felt at every level. Kids would tell me, “if you don’t like it, go back to your own country, or “dirty Jew” or derogatory remarks even from little children. And when we spoke Yiddish in public places, people would look at you and make remarks…right wing movements became very strong and..in 1938 came the Munich Agreement...” (following which Hitler, granted part of Czechoslovakia, began his invasion of Western Europe).

When France became occupied in 1940, the armistice signed by Philippe Pétain in collaboration with the Nazi regime divided France into two regions, the unoccupied south and the occupied north, which included Paris. In time the entire country would be occupied.

Life for Jews under the Vichy regime was harsh. Every aspect of daily existence was controlled by regulations.

“…they took away the shops. You were not allowed to own a business…and you had to surrender all your assets… shopping for food was limited for Jews to between three and four in the afternoon when there was no food left…you had to take the last car of the metro and ride at the back of the bus…”

In process of liquidation by Nazi decree, the small jewelry store owned by Armand’s great-uncle Turyn (on mother’s side), here with wife Rose. Note: Jewish star worn by Turyn.

“…Anti-Jewish propaganda increased tremendously. There were exhibits in which Jews were portrayed in (stereotypical caricatures), as greedy and trying to profiteer...” The Jew Suss,” a movie played throughout Europe, demonized Jews…And you could see a change in the population subjected to this kind of propaganda day after day, in the newspapers, on the radio…”

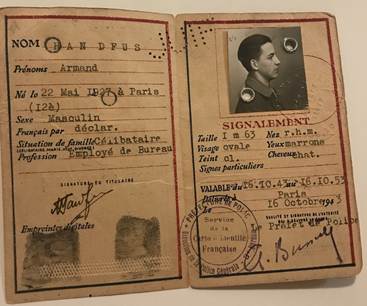

Armand describes how in 1941 you had to register as Jewish if you had any Jewish parentage. Armand’s parents registered, and in this way the authorities learned exactly who was Jewish and who was not.

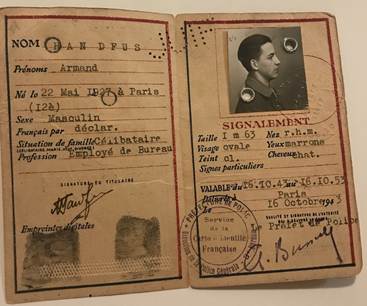

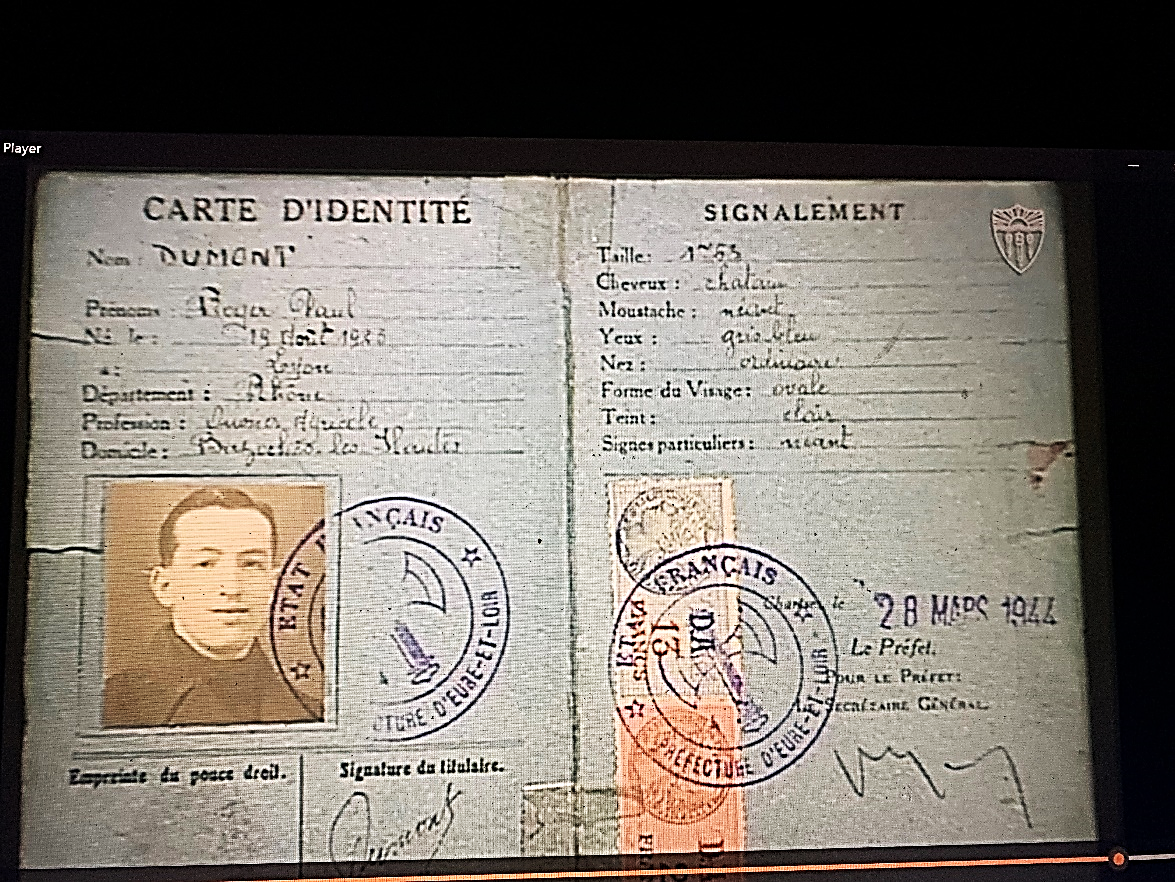

Armand’s identity card (JUIF), 1943. Note: perforation of word “Jew”, system established in 1943. It was formerly stamped in red. which could be erased by various methods.

In May 1942, a decree declared that all Jews six years and older had to wear a Jewish star. Armand wore it, everyone in his family wore it, his young brother, aged eight, wore it.

(Armand later donated two of his four stars to the Museum of Jewish Heritage, where they have been on display).

Uncut Jewish Star, Collection. Museum of Jewish Heritage

“…you had to buy them and even had to give textile points…”(the star had to be sewed because people pinned it and removed it quickly in case of a raid. It had to be tightly sewn. Otherwise you could be arrested, under suspicion of doing something illegal).

Meanwhile, the family was living in their renovated quarters which had been expanded to accommodate the growing family, the birth of young Robert.

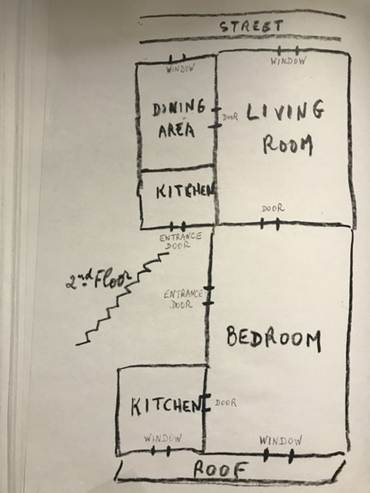

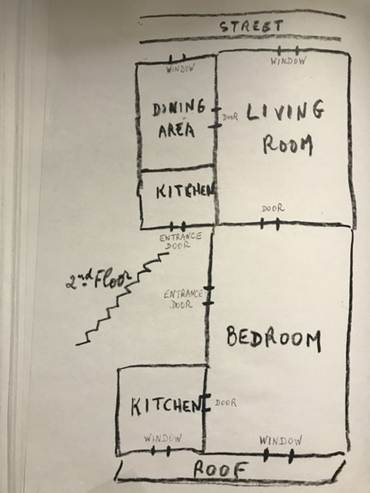

In 1934, a second, adjoining apartment had become available. It entailed breaking down a wall to form a single, conjoined five-room apartment with two kitchens and two entrances. One entrance was sealed and condemned.

Here is the event, born of desperation, which inspired Armand’s father to devise a hiding place for the family.

In mid-July 1942, rumors of a major round-up were circulating, just prior to the infamous Vel d’hiv roundup of July 16-17, in which 13,000 French Jews were arrested and deported by the French police.

In Armand’s words:

He (Max) said: “Since we have two kitchens, we are going to close-up one kitchen… he took out the doorknob and we pushed the wardrobe to block the door. Although you could see on the top of the wardrobe a little opening of the door, we placed some books on top to hide the opening and you could not see anything. And he said, “if they come, we will go out through the window (along the ledge) onto the little roof… and hide there in the little kitchen”

Armand’s sketch of the (enlarged) apartment.

Note: bedroom adjacent to kitchen, access through bedroom window onto ledge and into second (kitchen) window.

On the night of the roundup, July 16, Armand, his father, and Daniel slept fully dressed. At dawn the police knocked on the door. The three fled through the window (and along the outside ledge) and hid in the concealed kitchen space. Armand’s mother and young brother remained in the apartment because the family still believed that women and children were safe.

“…Two cops came in…they had an index card for each of us… …they asked (for each of us)…and they asked my mother to get dressed and follow them…and she started screaming…my mother was screaming, my brother was crying… because of the screams at six o’clock in the morning, the cops felt embarrassed and they said they said “ok, we will come back with a squad...”

From their hiding place Armand and his father looked out over a small neighborhood bridge and saw people being dragged away with bedding, suitcases. There were children, women, baby carriages. Only then did they understand that everyone was being arrested, including women and children.

Pedestrian bridge, holding area for Jews, night of Vel d’hiv round-up, July 16, 1942.

Then, on August 3, 1942, a few weeks later, the event occurred that would change Armand’s life forever:

On a visit to a neighbor, Armand’s mother Ita and young brother Robert (eight) would be arrested; they, with the other family, husband, wife and five children, a net of five Jews would be sent to Drancy and from there to Auschwitz where they would be murdered. Armand was present at his mother’s arrest. In Armand’s memory, the moment the doorbell (at the neighbor’s apartment) rang and two cops entered the neighbor’s apartment, for him, ...“time stopped...that particular fraction of time when the cops came in… I knew that everything would be different….”

A few days following this devastating event, Armand received a postcard he had written to his mother. It had been stamped “return to sender.” It was dated August 14, the day his mother and brother were deported. By the time he received it, they were on their way to Auschwitz. The postcard is in the Permanent Collection of the Museum of Jewish Heritage.

Postcard from Armand Handfus to his mother, Ita Handfus, and brother Robert in Drancy, in French, with some printed text in German, August 14, 1942.

Translation from French:

Paris, August 14th.

Dear Mother and dear Robert: I hope that you received the package of clothing as well as the two food packages which I sent you. I will send you on Monday a new food package. Everything goes well here. I am taking care of the house and I am in good health. I hope you are also in good health. Send me the food ration cards and respond to me right away. I hope to see you soon. A thousand kisses for you and for Robert.

A. Handfus

(Collection, Museum of Jewish Heritage)

Their apartment , in the course of the war, would be raided ten times.

The secret room narrowly escaped discovery. A few days following the arrest:

“…a quiet evening, sunny, peaceful, summer evening. All of a sudden you hear boots banging on the door. You don’t hear them going up the stairs. They tiptoe going up. On the table were two plates of soup. While my father was running to hide, I take one plate of soup and put it under a cabinet, then run into the other room and close the window behind him. And the venetian blind is still shaking from the movement…”

“…five cops come in and they push me…they run into the bedroom and see the blind still shaking. One of the cops opens the window, looks out and cannot imagine that the other window on the roof is part of the same apartment. He tells me, “Don’t worry, we’ll get your father, we know you are hiding him somewhere…and they leave.”

Now, a brief transgression:

Max and Ita were legal residents of France but remained Polish citizens. Their 1935 or 1936 application for French citizenship had been interrupted by the war. Max had legal work papers. There had been no problems, ever with the police. Armand, born in France, had been registered as a French citizen, which offered him limited immunity from arrest. Daniel, born in Poland and considered stateless, was the most vulnerable.

This by way of illustrating that there were no legal grounds for arrest, except for fabricated racial laws.

Still, In July, 1943, Max and Armand were about to be arrested.

Here is Armand’s account of the incident:

Armand’s father, Max, an artisan in the leather trade, delivering a piece of work to his Aryan employee (Jews had to be employed exclusively by non-Jews), on the staircase hears “Halt!”. The SS approaches Max and slaps him and demands to see his legal papers, which are at home, with Armand. He asks that they both return to the employer at 3:00 pm the next day, with their papers, to which request, Max, confident his papers are in order, acquiesces. A brief summary, as Armand describes it:

The next day Max and Armand return at 3:00 to the employer. The SS arrives at 3:30 (with a parked, chauffeured limousine waiting downstairs). He takes one look at the legal papers and declares, “…you are both arrested. I have received orders…this card is worthless…you are coming with us…let’s go back to your apartment for you to pack and that’s it…”

Meanwhile, Daniel, in grave danger of arrest, remains hidden in the kitchen when they return. He hears them pack, listens in terror to the conversation. Suddenly, the SS looks up at the books which are hiding the space behind the wardrobe.

“What is up there?” he asks.

“Nothing. Those are my school textbooks….”

Had he removed the books, he would have seen the door behind it. Armand’s heart at that point stopped beating. The SS simply said, “You pack.”

And so they packed, whatever they could fit in two suitcases. They went downstairs and entered the beautiful, chauffeured limousine.

“I am going to give you a tour of Paris because it is the last time you see Paris. He gave them the Grand Tour, showed them the Champs- Élysées, and said “Look around, you will never see Paris again, you better look around, nice…” And they stop, rue des Saussaies, which is Gestapo headquarters.

Following his mother’s and brother’s arrest, Armand, bringing a packet of food and clothing to the Jewish Committee (also known as UGIF) received an offer to work for them. A kindly clerk (subsequently deported), upon questioning the frightened, traumatized 15-year-old about his family situation, acted on his behalf to find him a place in the mail room, which would also to a limited degree afford him and Max immunity from arrest.

Raids occurred at the Jewish Committee, remembered in particular, when one of the leaders, a prominent Jewish banker refusing to reveal the whereabouts of a list of children to the SS, was with his four children and top leaders of the Jewish Committee arrested. Armand and a friend had devised an escape route across the roofs which they employed to avoid arrest, although the SS at the time, which they did not know, was arresting only leaders.

Before the Liberation of August 25, 1944, there was fierce street fighting and barricades everywhere. German soldiers were seen loading trucks and trains as they fled. Everyone sensed the war was ending. On Liberation Day, his brother Daniel, who had been hiding in the countryside under an assumed non-Jewish name, returned to the family, hitch-hiking home by jeep. It was after the war that they learned of the fate of Ita and Robert.

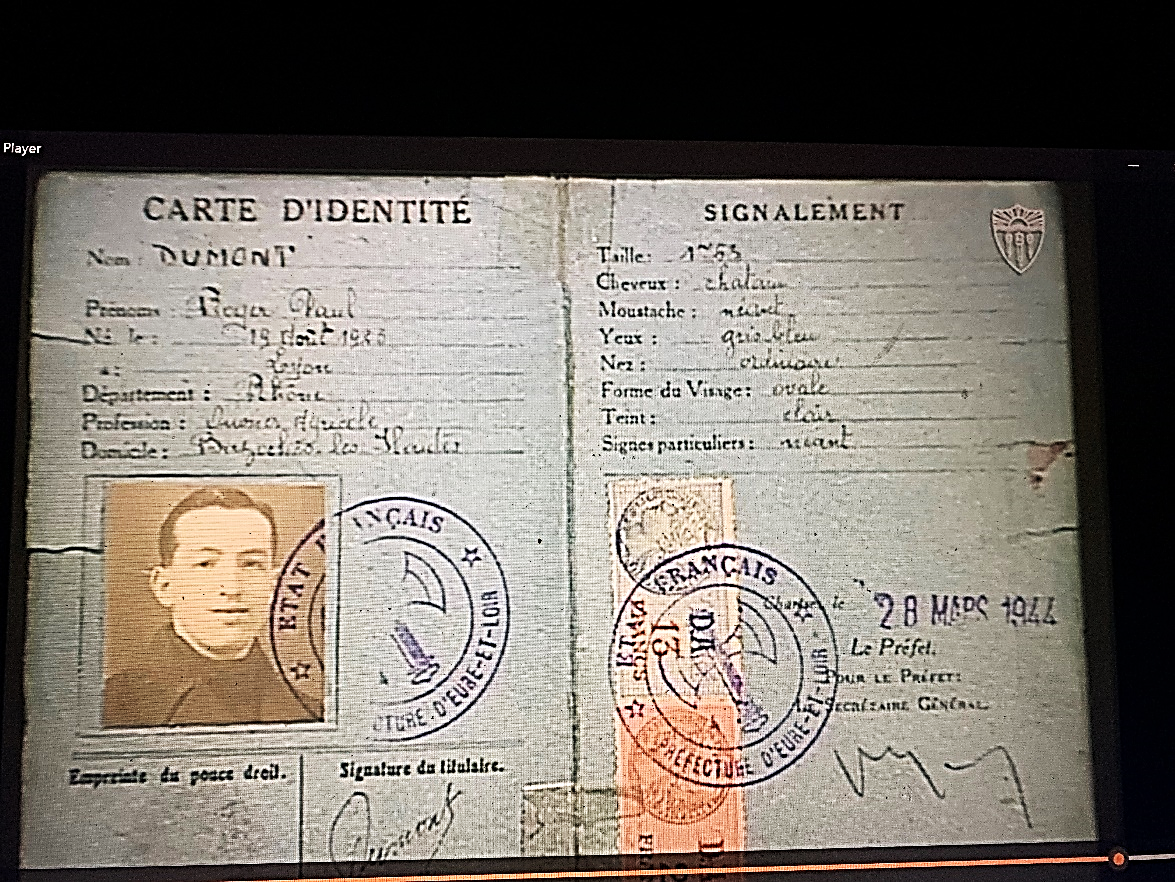

Daniel’s fake ID card with a non-Jewish name; it enabled him to flee Paris

and avoid arrest.

Photo, USC Shoah Foundation Videotape, Daniel Handfus

At the office, a group of Americans walked in and said, “We are the Joint Distribution Committee and you are hired and you will be part of the staff. The mad joy of experiencing all these events, the offer to work, the Liberation, cannot be imagined.

In 1946 Armand immigrated to the United States. While boarding the ship, his documents, due to a misunderstanding, were left behind on the tender and Armand, panicked that they were not on his person, rushed to the tender just as it was about to leave; there, high on the top of a mound of suitcases, his packet of documents. He almost missed the boat!

In America, after several unsatisfying jobs, he found work at the newly established United Nations. He remained, thriving and successful, eventually becoming supervisor of a large French proofreading department until retiring after 41 years, in 1987.

In his early years of retirement, he worked as a French translator for the Museum of Jewish Heritage. He was a member, volunteer, donor, and benefactor. The museum was a special place for him.

Armand died at the age of 92, beloved by wife Caroline, daughter Janine, and twin grandchildren, Josh and Eve. May his memory be a blessing.

Armand’s Bar Mitzvah, May 12, 2007. He was 80.

~By Handfus family, with special thanks to Deirdre Mooney Poulos