Story Summary:

The Kishinever Sick Benevolent Society, founded in New York in 1903 by Jewish immigrants from Kishinev (now Chișinău, Moldova), was established in the wake of the brutal Kishinev pogrom, a violent anti-Jewish riot that spurred mass emigration from the Russian Empire. The society, along with affiliated groups like the Kishinever Relief and Charity Society and the Kishinever Independent Ladies' Society, provided critical support including sickness and burial benefits, community gatherings, and cemetery plots at sites like Mount Hebron and Acacia. These organizations recreated the close-knit communal support of Eastern European shtetls and preserved the memory of a devastated Jewish community. Much of that community was later annihilated during the Holocaust. ~Blog by Deirdre Mooney Poulos

“The Kishinever Society: From Pogrom to Preservation in Stone”

Congregation Kishinever, also known as the Kishinever Sick Benevolent Society, was founded on December 23, 1903, in New York City by Jewish immigrants from Kishinev, now Chișinău, the capital of Moldova. The society was established in direct response to the devastating Kishinev pogrom, which occurred earlier that year in April and marked a grim turning point in modern Jewish history. Over the course of three days, anti-Jewish rioters killed at least 47 Jews, injured hundreds, and destroyed over 1,500 homes and businesses. The brutality of the pogrom was widely reported across the globe, prompting international condemnation and a surge of Jewish emigration from the Russian Empire. Many Kishinev survivors and their relatives fled to the United States, and those who settled in New York immediately organized for survival and cultural continuity. The Kishinever Sick Benevolent Society functioned not just as a burial and insurance group. It offered a lifeline, preserving the memory of their hometown while helping new immigrants navigate American life (Katzman, 2025).

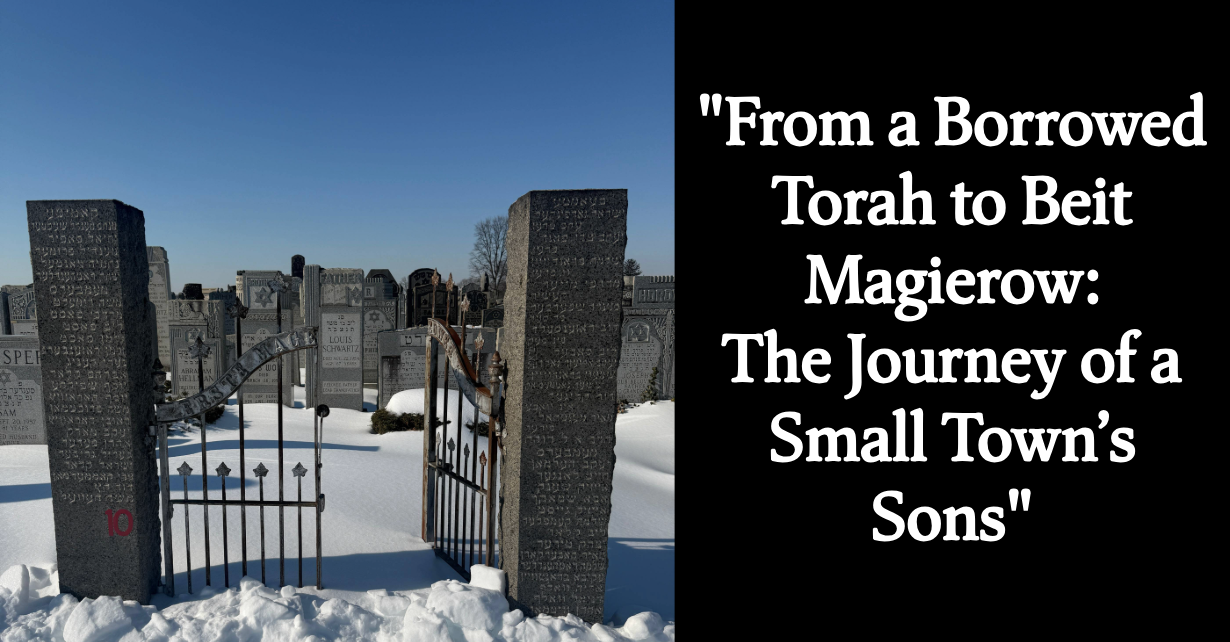

The society quickly became one of several Kishinev-based landsmanshaftn, or mutual aid societies, in the city. It later incorporated officially in 1913 and expanded to include affiliated groups like the First Kishinever Progressive Society (1907), the Kishinever Relief and Charity Society (1914), the Young Kishinever Benefit & Benevolent Society (1891), and the Kishinever Independent Ladies’ Society. Together, these organizations exemplified the model of grassroots immigrant support, providing sickness and death benefits, organizing holiday events, maintaining burial grounds, and offering communal support to members in times of crisis. In this way, they recreated the shtetl-style support networks of Eastern Europe in the urban setting of New York. Their cemetery plots at places like Mt. Zion, Mount Hebron, and Acacia Cemeteries served not just as burial grounds but as sacred sites where memory, tradition, and kinship were physically inscribed. These headstones, often marked with “Kishinever” identifiers, remain invaluable records of both individual lives and collective belonging (JewishGen).

Kishinev itself had been home to one of the most vibrant Jewish communities in the Russian Empire. At the dawn of the 20th century, Jews comprised nearly half of the city’s 125,000 residents, and the community boasted synagogues, schools, publishers, and civic leaders. Yet the pogrom of 1903, followed by a second in 1905, shattered this relative prosperity and marked the beginning of a long decline. These attacks were not spontaneous but facilitated by the tsarist authorities, and they catalyzed new movements for Jewish self-defense, immigration, and Zionism. The Kishinev pogrom became a symbol of modern antisemitism and featured prominently in Jewish advocacy and literature, influencing figures from Hayim Nahman Bialik to American reformers like Jacob Schiff and Emma Lazarus. For the immigrants who founded the Kishinever societies in New York, the trauma of the pogrom was inseparable from their identity. They were not just starting new lives. They were bearing witness to those who could not. These societies enshrined that history in ritual, record-keeping, and mutual responsibility.

The Holocaust would later annihilate what little remained of Kishinev’s Jewish life. Under Romanian and German occupation during World War II, tens of thousands of Jews from Bessarabia and Bukovina were deported to ghettos and concentration camps in Transnistria, where most perished. Although Kishinev had already lost much of its Jewish population to immigration before the war, those who remained suffered devastating losses. Today, there is no significant Jewish population in Chișinău, but remnants of synagogues and cemeteries remain, along with online archives and memorial projects that strive to reconstruct the town’s lost Jewish heritage. In the United States, organizations like the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, YIVO, and JewishGen continue to preserve these records, and cemetery plots maintained by the Kishinever societies stand as lasting monuments to a vanished community. For descendants and researchers alike, these societies and the stones they left behind offer a profound reminder of resilience, solidarity, and historical memory.

~Blog by Deirdre Mooney Poulos

Work Cited:

Abe Katzman: Kishinever Sick Benevolent Society History

https://alte.klezmor.im/2025/02/15/abe-katzman-and-the-kishinever-sick-benevolent-society-of-new-york-inc

Jewish Genealogical Society of New York – Landsmanshaftn Archives (via YIVO)

https://jgsny.org/?catid=34&id=135%3Ayivo-landsman-archive&view=article

Wikipedia – Kishinev Pogrom

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kishinev_pogrom

Jewish History Timeline – Kishinev Pogrom

https://www.jewishhistorytimeline.com/timeline/1903-ce-the-kishinev-pogrom