Story Summary:

Marian Boykan Pour-El was a trailblazing mathematician whose work reshaped the understanding of logic, computation, and physics. Born in New York City in 1928, she earned her Ph.D. from Harvard at a time when few women pursued advanced mathematics and went on to become a respected professor at the University of Minnesota. Her research revealed that even simple physical systems can behave in ways that defy computation, challenging ideas about predictability in science. Beyond her groundbreaking discoveries, she also broke barriers for women and Jewish scholars in academia, leaving behind a legacy of intellect, resilience, and inspiration. ~Blog by Deirdre Mooney Poulos

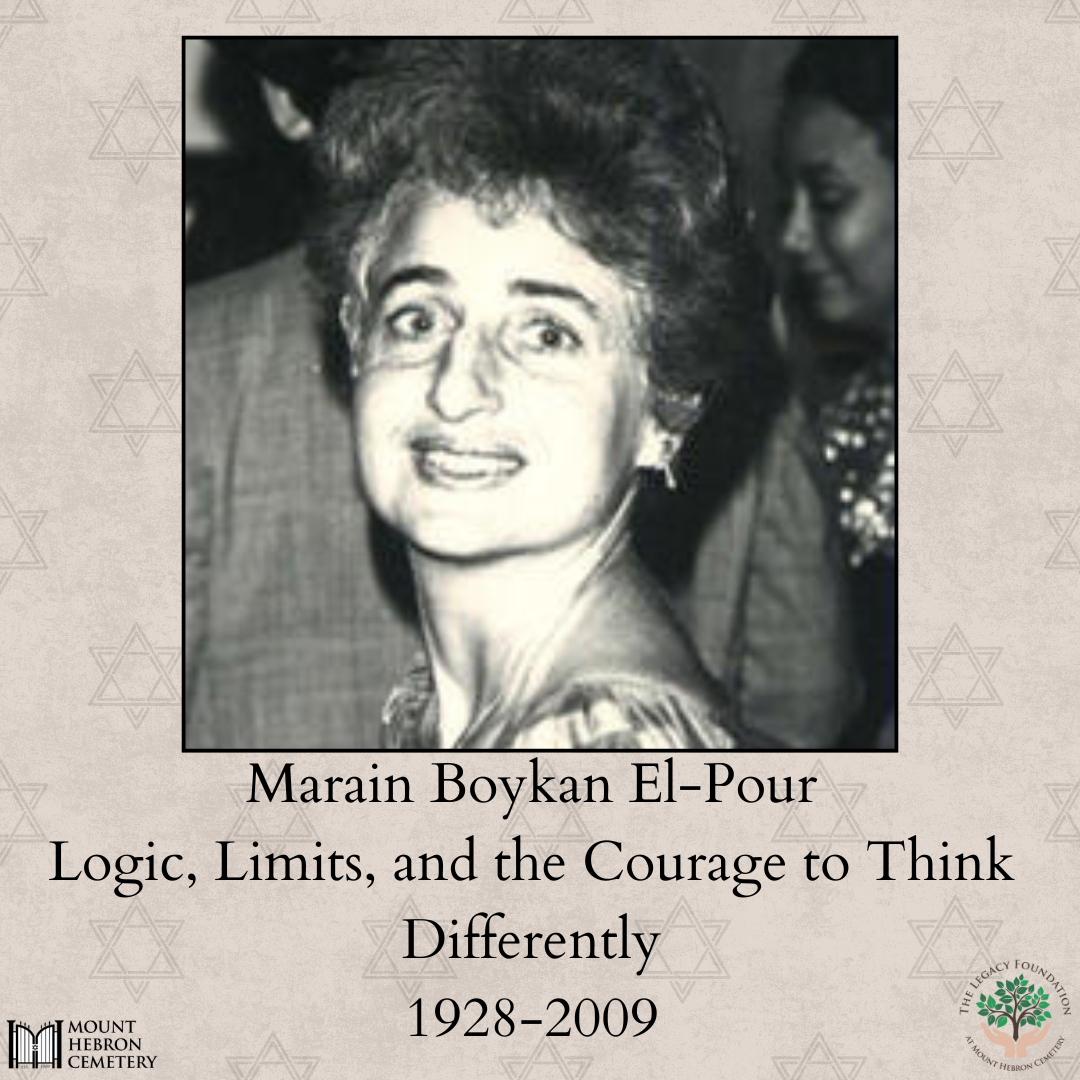

Marian Boykan Pour-El: Logic, Limits, and the Courage to Think Differently

In the story of twentieth-century mathematics, there are people whose names quietly changed how we understand the world. One of them is Marian Boykan Pour-El, a mathematician whose work in logic and computability opened new doors in science and whose life showed how courage and intellect can overcome barriers of gender and faith.

Marian was born in New York City in 1928 to Joseph and Matilda Boykan. She grew up in a time when very few women were encouraged to study advanced mathematics. During the 1930s and 1940s, women were expected to choose fields such as teaching or literature. Mathematics was considered a man’s pursuit, and women who entered it often faced skepticism or open hostility.

Marian attended Hunter College, where she studied physics and graduated in 1949. She had also taken enough mathematics courses for a second major, but the college did not allow women to earn a double major at that time. It was a small but telling sign of how institutions quietly limited women’s ambitions. For Marian, such limits were never acceptable.

After college she went to Harvard University, where she was often the only woman in her department. Harvard in the 1950s was not a welcoming place for women in science. They could not join the same clubs or attend the same discussions as men, and many faculty members treated them as curiosities rather than colleagues. Marian chose to specialize in mathematical logic, a field that straddled mathematics, philosophy, and the emerging ideas of computer science. There were no logicians at Harvard to advise her, so she traveled across the country to the University of California at Berkeley to finish her doctoral work. She earned her Ph.D. in 1958.

That year was a time of great excitement in science. The United States had just launched its space program, and computers were beginning to change research and industry. Marian’s choice of field could not have been timelier. She was asking questions about what it truly means for something to be “computable.”

After completing her doctorate, she joined Pennsylvania State University, where she advanced from assistant professor to associate professor and received tenure in 1962. At a time when very few women held tenure in mathematics, this was a remarkable accomplishment. She later spent two years at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, where she worked near the great logician Kurt Gödel. Gödel had shown that there are mathematical truths that cannot be proven within any formal system. Marian was inspired by this kind of thinking, which explored the boundaries of what the human mind can know.

In 1964, she joined the University of Minnesota, where she taught and researched for the rest of her career. She became a full professor in 1968 and remained an active scholar and mentor until her retirement in 2000. Students remember her as demanding but fair, a teacher who expected precision yet encouraged creativity.

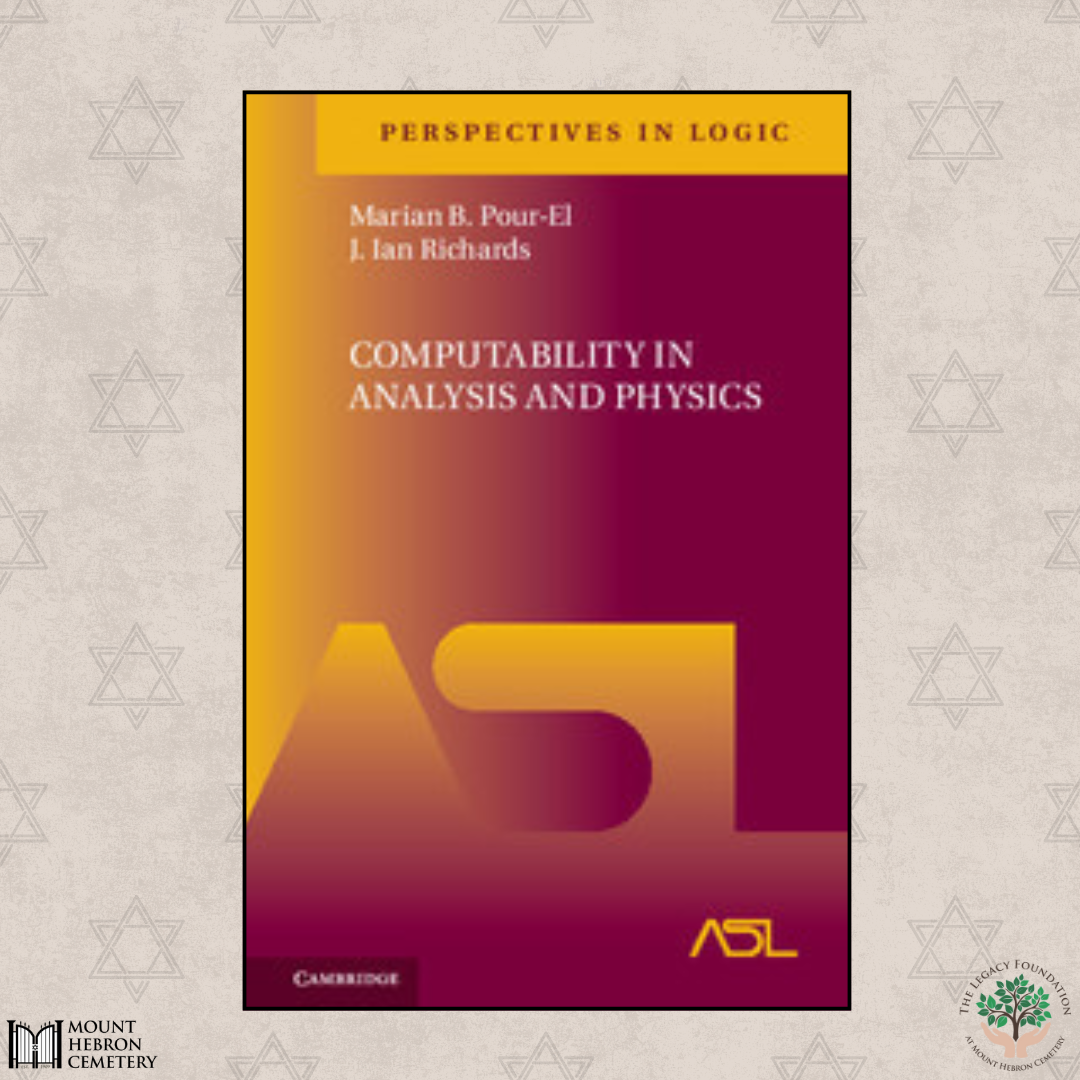

Marian’s most famous work, written with her colleague J. Ian Richards, dealt with the mathematics of computability in physics. They studied the wave equation, a fundamental equation of motion used in physics, and made a discovery that startled the scientific world. They proved that there are cases where the starting data for the equation can be fully computable, yet the resulting solution is not computable at all. This means that even when you know everything about how a system begins, it may still evolve in a way that no algorithm can predict.

This idea reshaped how mathematicians think about the limits of computation. It showed that mathematics and physics are not only about finding solutions but also about understanding the boundaries of what can be known. Marian and Richards later wrote a book called Computability in Analysis and Physics, which became a landmark in the field.

Marian’s achievements were remarkable, but her journey was far from easy. In the 1950s and 1960s, women who pursued advanced degrees in mathematics faced constant challenges. During that decade, fewer than two hundred women in the entire United States earned doctorates in mathematics. Many universities refused to hire married women as faculty members, believing they would soon leave to raise families. Those who did secure positions often found themselves excluded from research groups or denied promotions.

Marian balanced her work with her responsibilities as a wife and mother, something almost unheard of at the time. She spoke candidly about how difficult it was to combine family life with a research career when there were no examples to follow. Her experiences were later featured in Claudia Henrion’s book Women in Mathematics, which profiles women who broke barriers in their fields.

Her struggles were not only about gender. As a Jewish scholar coming of age in mid-century America, she belonged to a community that had long faced exclusion in higher education. From the 1920s through the 1940s, elite universities such as Harvard, Yale, and Princeton used quotas to limit Jewish enrollment. Even after those policies disappeared, antisemitism continued in more subtle ways. Jewish faculty members were often denied housing in certain neighborhoods, and some social clubs quietly barred them from joining.

By the time Marian began teaching, the most blatant forms of discrimination had started to fade, but bias still lingered in university culture. That context makes her achievements even more significant. She not only entered a field that excluded women, she also rose to prominence in institutions that had only recently begun to welcome Jewish scholars as equals.

Throughout her life, Marian believed that intellectual curiosity should be stronger than social convention. She mentored countless students, encouraging them to ask hard questions and to think deeply about the nature of truth and computation. She once wrote that mathematics was not just about solving problems but about discovering where the limits of understanding begin.

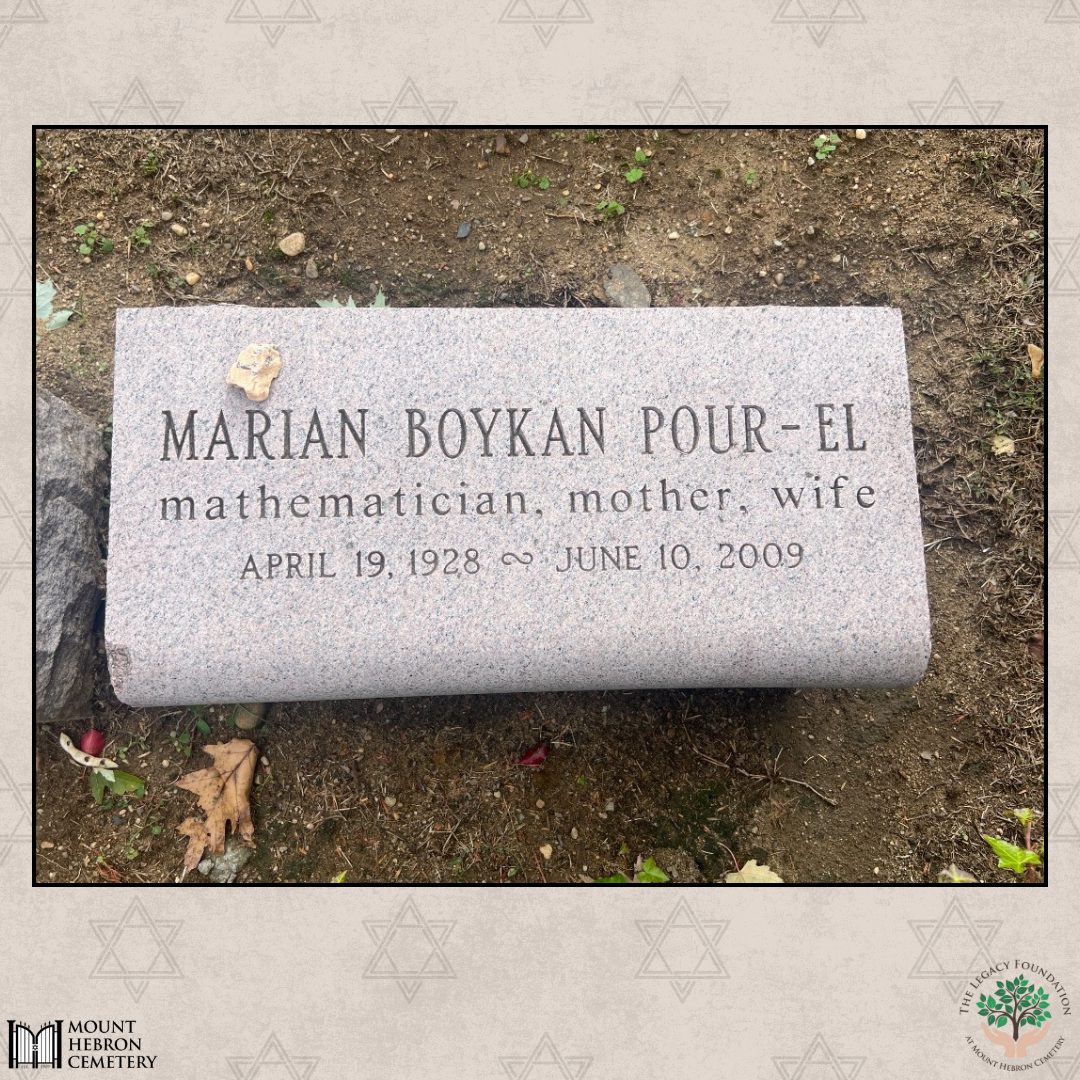

She retired in 2000 after more than three decades at the University of Minnesota. Even in retirement she continued to follow new research and stayed in touch with former students and colleagues. Marian Boykan Pour-El passed away in 2009 at the age of eighty-one. Her colleagues remembered her not only as a brilliant logician but as someone who brought warmth and humanity into a field that could easily feel cold and abstract.

Today, her work remains a cornerstone of computable analysis, the study of what can and cannot be calculated within the laws of mathematics and physics. Her book and papers are still cited by researchers exploring the limits of artificial intelligence and the theory of information. Yet her personal story may be her most enduring legacy.

When Marian began her career, women made up only a few percent of all mathematics Ph.D. holders. Today, about one third of doctorates in the field go to women. That progress owes much to the persistence of people like her, who worked in isolation but refused to give up. She showed that it is possible to be both rigorous and compassionate, both ambitious and humane.

Her life reminds us that progress in science is not only about discoveries or theorems. It is also about opening doors. Marian Boykan Pour-El lived at a time when those doors were often closed to women and to Jewish scholars. She opened them quietly, with patience and brilliance, so that others could follow. In doing so, she left a mark that continues to grow long after her equations have faded from the blackboard. ~Blog by Deirdre Mooney Poulos