Story Summary:

From a small Galician town once alive with prayer and learning to a brotherhood forged in the tenements of New York, this story traces the remarkable journey of Magierow's Jews across continents and generations. It is a story of loss and survival, of a community destroyed in Europe but rebuilt through mutual aid, faith, and memory in America and Israel. Beginning with a borrowed Torah and a few dollars, the Erste Magierower Society became a living bridge between past and present, ensuring that the spirit of Magierow would endure long after the town itself was silenced.~Blog Written by Deirdre Mooney Poulos & Matthew Brown

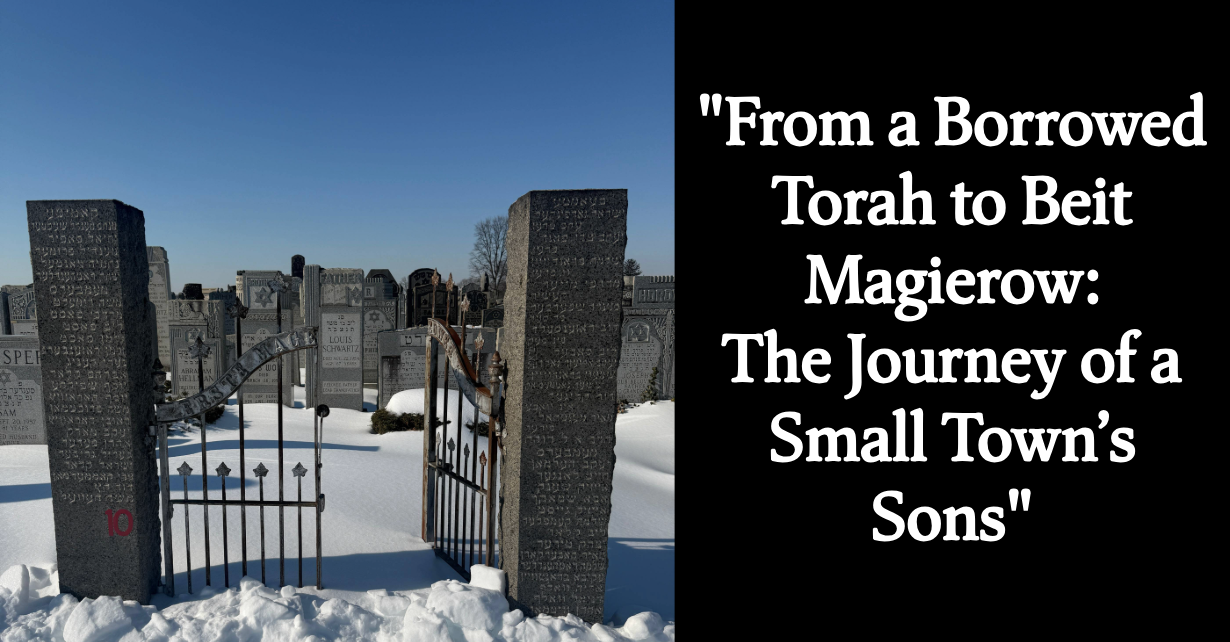

"From a Borrowed Torah to Beit Magierow: The Journey of a Small Town’s Sons"

Magierow, known today as Maheriv, is a small town about thirty kilometers northeast of Lviv. Before the Second World War it was home to a lively Jewish community, one of many that dotted the landscape of eastern Galicia. The town was founded in 1591 by a Polish noble who originally forbade Jews from settling there, yet within a few decades Jewish families had arrived and slowly built a presence through trade and craftsmanship. By the late nineteenth century more than forty percent of the town’s residents were Jewish. They worked as tailors, shoemakers, and small merchants, and their days revolved around a sturdy stone synagogue and nearby study houses. The sound of prayer and song filled its narrow streets, especially on Fridays as families prepared for Shabbos.

Rabbis of the Epstein and Rappaport families guided the community. Belz Hasidic influence was strong, and the piety of Magierow’s Jews became well known in surrounding towns. After the devastation of World War I, when Russian and Austrian armies fought across Galicia and burned much of the town, help came from Jewish relief organizations in America. They sent money to rebuild homes and restore the synagogue. In the 1920s and 1930s Magierow once again became a place of learning and faith. Children attended Hebrew schools and Beit Yaakov classes. There were Zionist youth groups, a library, and even a sports club. But beneath this renewal there was tension. In 1936 a Jewish family in a nearby village was attacked, a grim warning of the hatred gathering strength in Europe.

In September 1939 the Germans invaded Poland. Magierow fell briefly under German control and then was taken by the Soviets, who closed many Jewish businesses and arrested several men. Two years later the Germans returned and within months began rounding up the Jews. In the spring of 1942, on Passover, German and local police seized many of the town’s Jews, shooting some on the spot and sending others to nearby Rawa Ruska. From there they were transported to the Belzec death camp. A few skilled workers were spared for a time but were soon deported as well. By autumn Magierow’s Jewish life was gone. Only fragments of tombstones remain in the overgrown cemetery, the last witnesses to centuries of presence.

Although the town’s Jewish community was destroyed, its spirit lived on in New York City through the Erste Magierower Society, a group founded in 1908 by immigrants from the town. They were young men then, recent arrivals to America who worked in shops and factories on the Lower East Side. Around twenty Magierower landsleit were living there, most of them in the streets around Rivington, Attorney, and Willett. They prayed in other people’s synagogues, often as guests. One Yom Kippur, the story goes, their friend Yankev Fond, who served as a gabbai in the Gross Moster Shul, honored his fellow Magierowers with Torah readings. Some congregants objected. Fond turned to his landsleit and said, “We are strangers here. We need our own home.”

After the fast they met in the apartment of Shloyme Rothendler on Rivington Street. Each man contributed a dollar and together they created the Magierower Society. The first names on the list were Isaac Tirer, Yankev Fond, Chaskel Rothendler, Ikhl Sapir, Moishe Rumelt, Shimon Brandwein, and others. Within days they borrowed a Torah from the Zholkiewer congregation, held their first prayer service, and soon rented a small meeting room on Delancey Street. That room became their synagogue and community center. They gathered for Shabbos services, holidays, and meetings, speaking in their familiar Yiddish and easing the homesickness of new arrivals who missed the life they had left behind in Galicia.

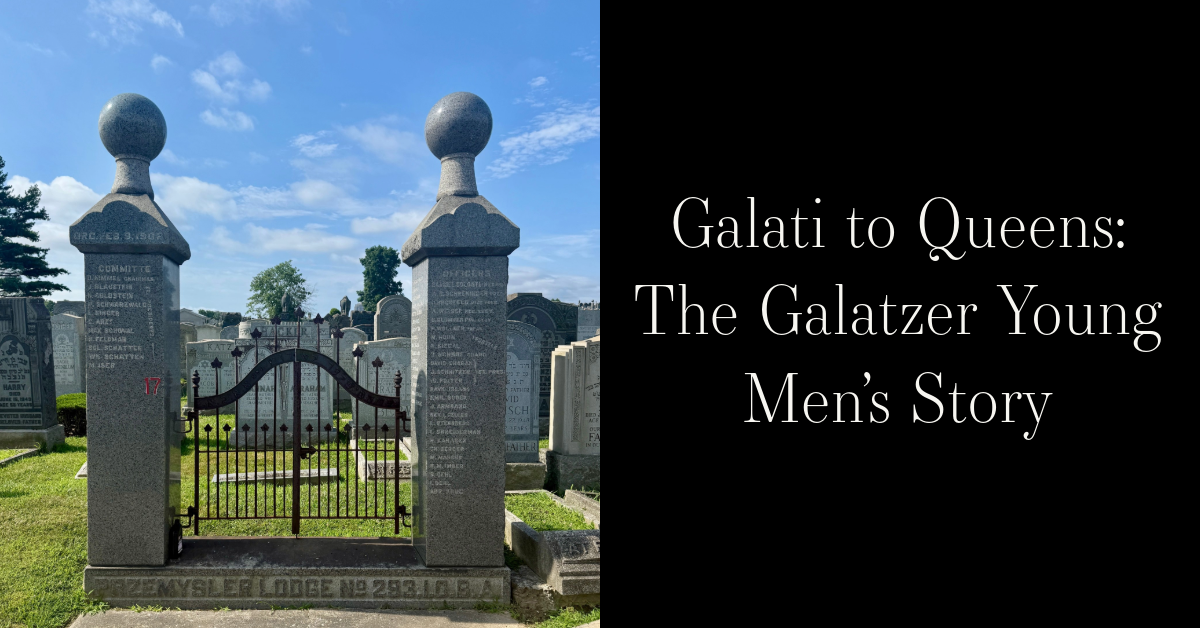

The society quickly took on practical purposes. It created a sick benefit fund, provided small loans, and established a burial plan. When a member fell ill, a committee visited him and quietly left money for his family. They raised enough to buy cemetery land at Mount Hebron in Queens, which became sacred ground for generations of Magierowers in America. Membership meant more than social belonging. It meant protection from eviction and the comfort of knowing that in illness or death, one would not be alone.

When the First World War broke out in Europe, the Magierower Society came into its own. News arrived that Magierow had been devastated by fighting and that even the cemetery wall had been torn apart for road construction. The society raised funds to rebuild it, to repair the synagogue and heat the study house through winter. They sent a delegate back to the old town with cash to distribute among needy families. The connection between New York and Magierow remained strong through the 1920s and 1930s. Members of the society also helped new immigrants from neighboring towns, finding them lodgings and jobs. Their names—Fond, Brandwein, Yaner, König, Scheinert, Rumelt, Methal, became known for kindness.

As the Second World War approached, the society continued its charitable work, supporting Jewish hospitals, yeshivas, and homes for the aged. During the war they raised funds for the Vaad Hatzalah and celebrated when their sons who served in the American military all returned safely. When the full horror of the Holocaust reached them, they grieved together. In the years that followed they turned their hearts toward helping survivors and supporting the newly established State of Israel. They bought Israel Bonds and financed the building of a house in Israel called Beit Magierow, a memorial to their destroyed hometown. They also sent two Torah scrolls to new kibbutzim, ensuring that Magierow’s spiritual legacy would live on.

By 1958, when the society marked its fiftieth anniversary, it had become one of the respected landsmanshaft organizations in New York. The founding generation had grown old, but their children had become professionals and community leaders. The anniversary booklet listed names that still echoed the founding generation: President William Yaner, Vice President Joey Meritz, Finance Secretary Max Rumelt, Recording Secretary Shloyme Sheynert, and Trustee Dr. Sol Brandwein. These younger leaders carried on the work their fathers had begun half a century earlier. “Here in the Magierower Society,” said Rumelt, “that my father and your father built, this is where I feel at home.”

The 50th anniversary booklet spoke warmly of the society’s founders, men who once lived in cold-water flats and worked long hours but still found time to help others. It remembered how they visited the sick, raised money for the poor, and offered guidance to new arrivals from Europe. It praised those who served as presidents, secretaries, and treasurers, often for decades, and recalled the faithful caretakers of the Magierower Synagogue on the Lower East Side, including the beloved shames, Yankel Landes, who served for nearly forty years. The article reflected pride in the younger generation’s education and achievements but also a deep sense of continuity. The founders’ children had not forgotten who they were or where they came from.

As the society looked to the future, its members saw themselves as part of a larger story. They understood that the Jewish people in America had become a vessel for the survival of traditions lost in Europe. Their society was no longer just a mutual aid club but a link between worlds, a small bridge connecting theMagierow of Galicia with the living Jewish life of New York, America, and Israel.

Today, the graves of the Erste Magierower Society members at Mount Hebron Cemetery stand quietly among the rows of other landsmanshaft plots. The stones bear familiar names in Hebrew and English, testifying to lives shaped by faith, labor, and loyalty to one another. The town of Magierow may have been destroyed, but through the society its memory endured. The immigrants who once crowded the tenements of the Lower East Side left behind something lasting, a brotherhood that began with a few dollars and a borrowed Torah and grew into a legacy of care and remembrance that still speaks to the strength of community and the power of memory.

Special thanks to Matt Brown for providing the souvenir brochure, translations, and photos. His ancestors are from Magierow, and he has spent twenty years researching his family and this landsmanshaft.

~Blog Written by Deirdre Mooney Poulos & Matthew Brown

Sources and References:

- Pinkas Hakehillot – Yad Vashem: https://www.yadvashem.org

- ESJF European Jewish Cemeteries Initiative: https://www.esjf-survey.org

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum: https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org

- Erste Magierower Society Golden Jubilee Book (1908–1958): New York Public Library Digital Collections https://digitalcollections.nypl.org

- YIVO Institute for Jewish Research: https://yivo.org

- POLIN Museum Virtual Shtetl: https://sztetl.org.pl

- Mount Hebron Cemetery: https://www.mounthebroncemetery.com

- Fordham University Jewish Studies: https://jewishstudies.ace.fordham.edu

- New York Public Library – Dorot Jewish Division: https://www.nypl.org/locations/divisions/dorot-jewish-division