Story Summary:

Nathan Wasserberger (1928-2012) was a Polish-born Jewish American painter and Holocaust survivor whose art journey led from the trauma of Buchenwald to luminous portraits of women in kimonos and serene nudes. After emigrating to the U.S. in the late 1940's, he studied at renowned art institutions in New York and Paris, eventually shifting from dark Holocaust themes to vibrant, introspective figure painting. His work, celebrated for its sensuality and emotional depth, became a means of healing and reclaiming beauty in the face of past horrors. Today, Wasserberger's legacy lives on in the Smithsonian's archives, reflecting his transformation from survivor to celebrated artist. ~Blog by Deirdre Mooney Poulos

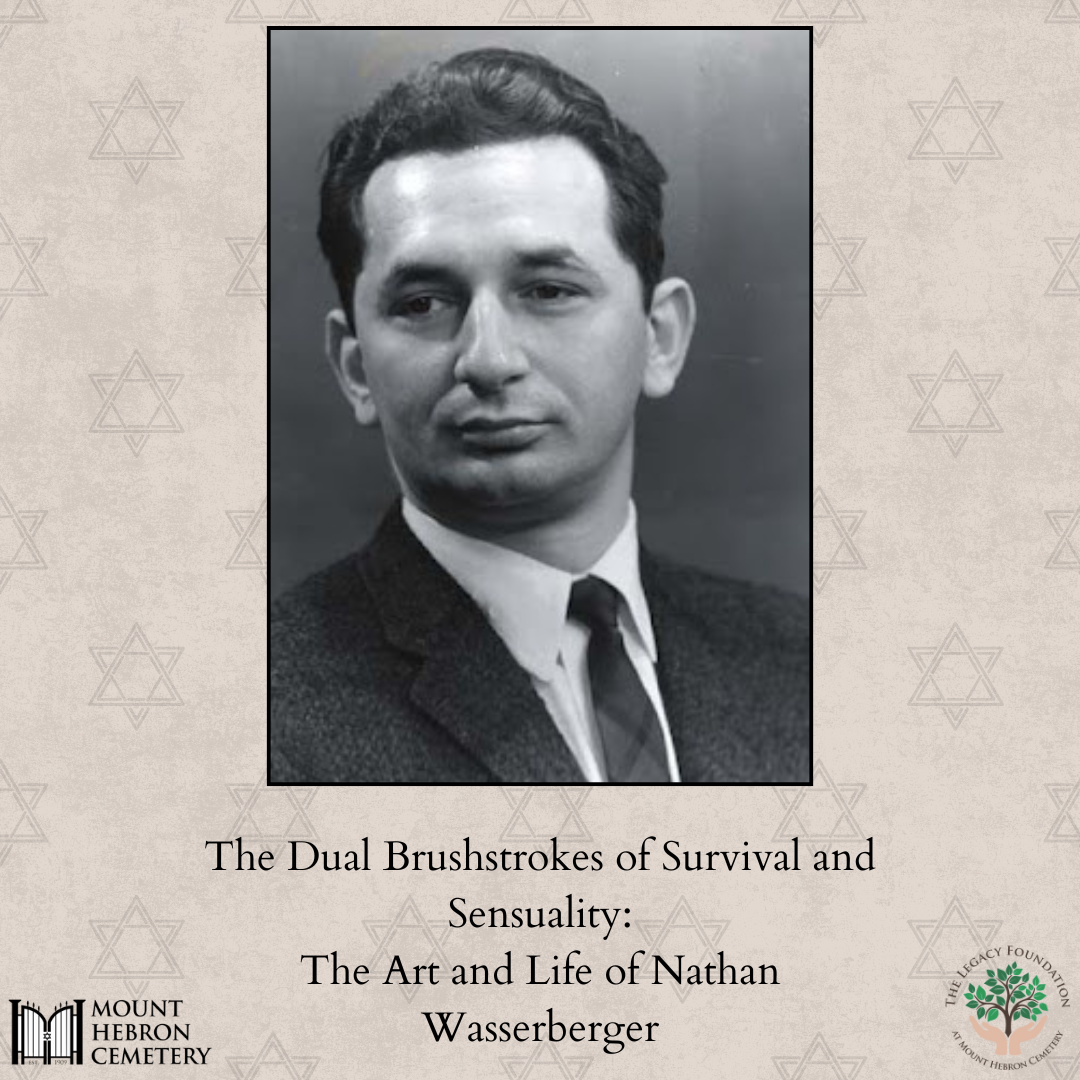

Nathan Wasserberger:

From Survival to Serenity in Brushstrokes

Nathan Wasserberger (1928 to 2012) was not only an acclaimed painter of women in luminous kimonos and ethereal nudes. He was also a Holocaust survivor whose art bore the silent weight of his past. His life stands as a testament to the transformative power of beauty, the resilience of memory, and the ability to rebuild a fractured identity through creative expression.

Born in Chrzanów, Poland, Wasserberger came of age in the shadow of the Holocaust. His childhood was interrupted by the Nazi invasion of Poland in 1939, when he was just 11 years old. Like many Jews from southern Poland, he was swept up into the machinery of the Holocaust, possibly surviving ghettos, forced labor, or even concentration camps. While specific details of his wartime experiences remain elusive, perhaps intentionally so, his survival alone speaks volumes. After the war, like many displaced Jews, he found himself in a broken Europe, searching for family, identity, and stability in the aftermath of genocide.

In 1946 or 1947, still in his teens, Wasserberger emigrated to the United States. He was part of a wave of Jewish refugees who arrived in America after surviving unimaginable loss. Here, in a new land, he not only found safety but also the conditions to nurture his voice as an artist.

Wasserberger threw himself into formal art training, studying at the Art Students League of New York and later at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. He combined the precision and discipline of classical European training with a distinctly modernist sensuality. His canvases would become known for their remarkable technical mastery, opulent textures, delicate light, and above all, the rich emotional subtext hidden beneath poised figures.

Wasserberger’s work is best known for its portrayal of the human form, particularly women, either nude or draped in intricately patterned kimonos. These figures, however, were not merely erotic muses or decorative studies. They were enigmatic presences—serene, introspective, and often emotionally distant. Their gazes averted, their postures composed, these women seemed suspended in time, as if reflecting an inner world we are only allowed to glimpse.

The kimono became a recurring motif, exotic, elegant, and full of symbolism. In Wasserberger’s hands, the garment became a second canvas—richly colored, full of folds and texture, a surface for emotional projection. The interplay between the vibrant garment and the quiet stillness of the subject created a kind of psychological tension. For a man who had seen humanity’s worst, these paintings may have represented a private meditation on identity, fragility, and survival.

The choice to paint beauty, not horror, was no accident. For Wasserberger, art was not a place to relive trauma. It was a space for reclamation. The dignity he gave his subjects, the grace he coaxed out of posture and light, was perhaps his way of restoring humanity in a world that once stripped it away.

Unlike many survivors who chose to share their stories in oral testimonies or memoirs, Wasserberger’s past remained largely private. There is no widely published firsthand account of his Holocaust experiences. And perhaps that silence was itself part of his artistic ethos. Instead of speaking of horrors, he painted serenity. Instead of recalling death, he captured life, delicate, stylized, and profound.

Yet the shadow of his past can be felt in the emotional undercurrents of his work. The women he painted seem both intimate and remote, inviting the viewer to look but not enter. There is a duality here—a desire for connection and the preservation of emotional distance, a dynamic familiar to many survivors.

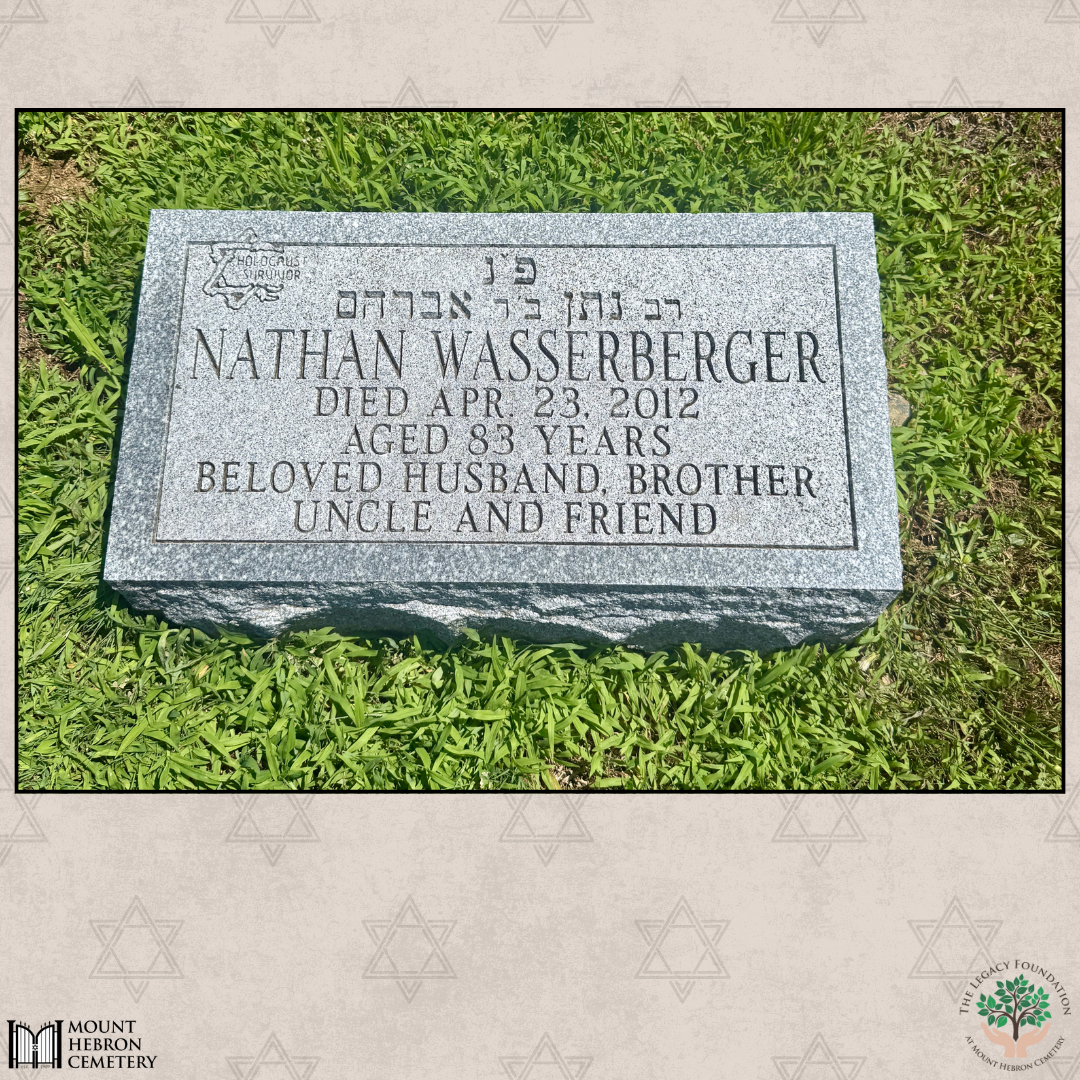

Though Wasserberger passed away in 2012, his work continues to resonate. The Archives and Special Collections of the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C. now house seven photographs of the artist and 67 photographs of his paintings. These archival materials allow future generations to trace his visual evolution, his mastery of the human figure, and his unique ability to merge pain with beauty.

His presence also enriches the broader tapestry of Jewish-American cultural history, a lineage of artists, writers, and thinkers who emerged from the ruins of Europe and helped shape postwar identity in the United States.

Nathan Wasserberger’s life was marked by profound contradiction. He was a survivor who painted serenity, a man whose early life was defined by chaos and dehumanization, who later chose to depict grace, poise, and mystery. His work is not merely beautiful—it is resilient. It reminds us that memory can take many forms. For Wasserberger, it emerged not in words, but in brushstrokes. And through those strokes, we see not just his subjects, but the deep human longing to reclaim dignity, meaning, and connection after loss. May his memory be a blessing.

~Blog by Deirdre Mooney Poulos

Work Cited:

Smithsonian American Art Museum – Archives of American Art

https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/nathan-wasserberger-papers-10513

AskART – Nathan Wasserberger Biography

https://www.askart.com/artist/Nathan_Wasserberger/106408/Nathan_Wasserberger.aspx

RoGallery – Nathan Wasserberger Artist Page

https://www.rogallery.com/wasserberger_nathan/wasserberger-biography.html

Wikipedia – Nathan Wasserberger

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nathan_Wasserberger

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM)

https://www.ushmm.org