Story Summary:

The Independent Wizner Society, founded in New York in 1901 by immigrants from Wizna, Poland, began as a mutual aid and burial society but became a keeper of memory after the Holocaust. Wizna's once vibrant Jewish community was destroyed in 1941 through bombings, massacres, and deportations, with many perishing in Jedwabne, the Lomza Ghetto, and Auschwitz. Survivor testimonies recall the terror of those days and the betrayal by neighbors. Today, the society's gate at Mount Hebron Cemetery stands as one of the only surviving monuments to the town, a threshold between past and present that affirms Wizna's memory endures. ~Blog by Deirdre Mooney Poulos

"From Wizna to Queens: Memory, Exile, and the Independent Wizner Society"

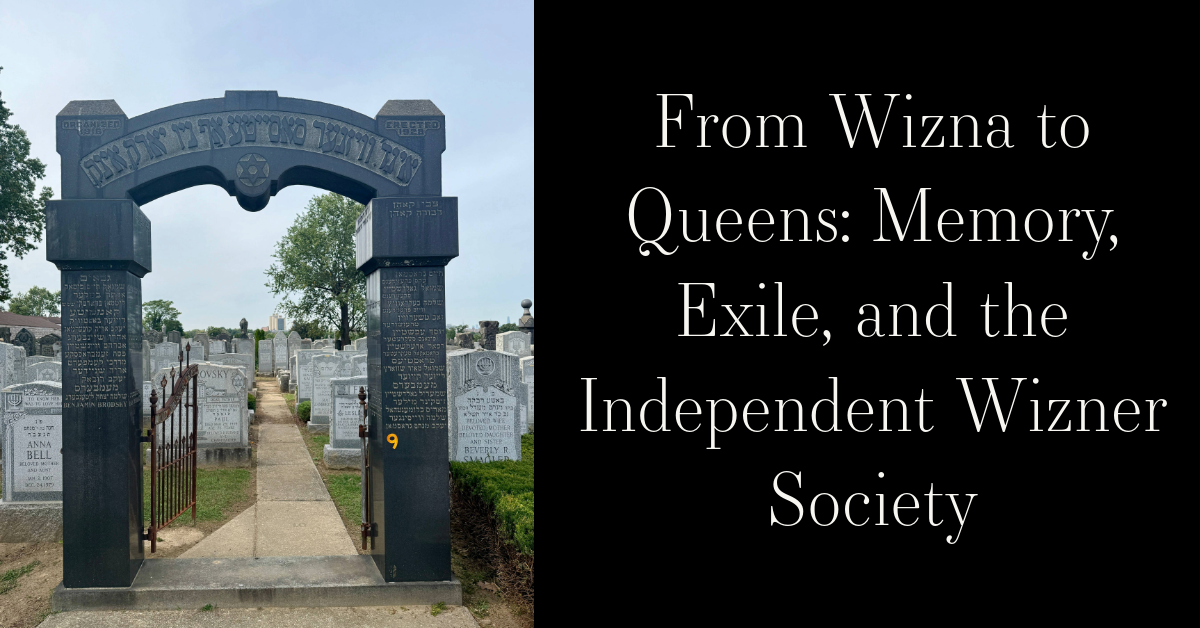

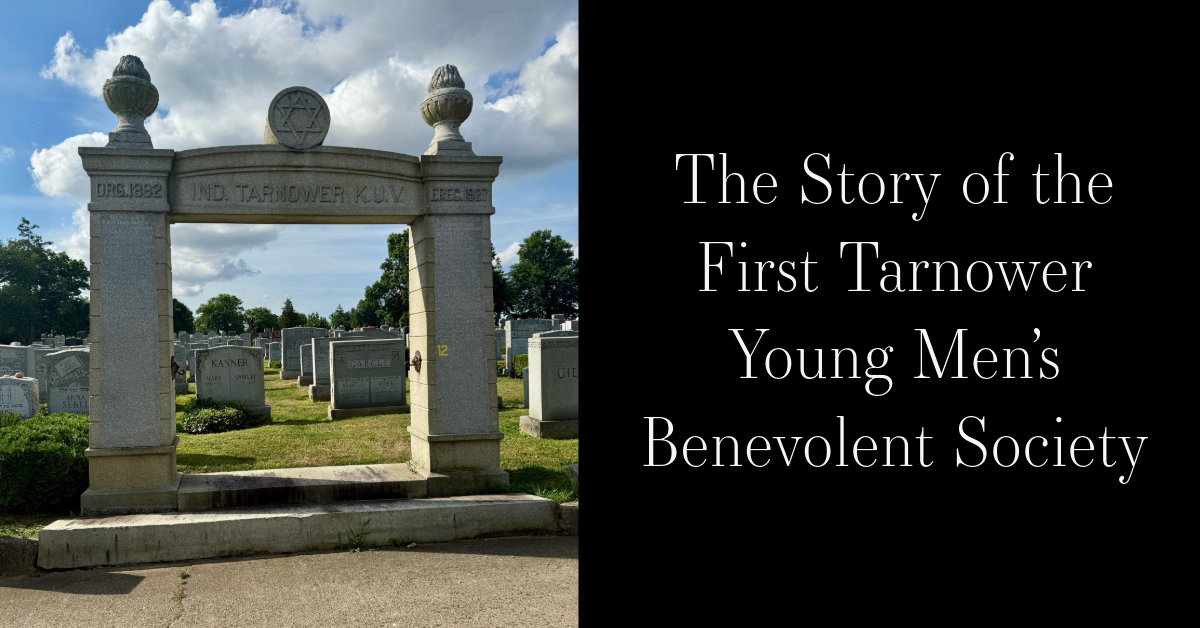

If you walk through Mount Hebron Cemetery and stop at the gate of the Independent Wizner Society, you will find yourself standing before more than iron and stone. You will be facing a link between a vanished town in northeastern Poland and the community that rebuilt its presence in New York. The Independent Wizner Society, created in 1901 by immigrants from Wizna, gave its members a way to carry their hometown with them across the ocean. It began as a mutual aid group, one of the many landsmanshaftn that flourished in the immigrant neighborhoods of the city. For the first generation, the society meant support in sickness and in need, and the assurance of burial among their own people. For the next generation, after the war, it became something even heavier. It became the keeper of memory.

Wizna before the Second World War was a small town but its Jewish community was full of life. Families owned small shops, worked as blacksmiths and tailors, studied in schools, and filled the synagogue on the Sabbath. Children learned prayers and Hebrew letters, women shopped in the market, and men debated politics in the evenings. There were struggles with poverty and anti-Jewish prejudice, but Wizna’s Jews had lived there for centuries and thought of it as home.

By the early 1900s, some families began leaving Wizna for America. They were driven by the same forces that carried so many Jews across the Atlantic: poverty, pogroms, and the hope for better opportunities. In New York, these immigrants crowded into tenements, worked long days in sweatshops or pushed carts through the streets, and saved what they could. But they also longed for the familiar ties of the shtetl. Out of this longing, the Independent Wizner Society was born. It gave them a circle of belonging, a way to preserve their town’s identity, and a place to secure graves so that in death they could still be near one another.

The ties across the ocean held until the summer of 1941, when Germany invaded the Soviet-held territories of Poland. Wizna was among the first places to suffer. On June 22, German planes dropped bombs that set fire to the Jewish quarter, destroying hundreds of homes. Families who had lived there for generations stood watching their houses reduced to ashes. Two days later, German soldiers arrived and violence against Jews began at once. Local collaborators joined in, murdering three people in the streets and chasing others into the countryside. Those who tried to hide were dragged out, beaten, and handed over to the Germans.

On June 26, one of the most terrifying events took place. Around twenty Jews were forced into a smithy by local Poles. A German soldier threw grenades inside, blowing apart the building and killing everyone within. For decades this story was known only from survivor accounts, until 2019 when a mass grave was uncovered near Wizna, believed to contain some of these victims. The horror of that day was carved into the memory of the few who lived through it.

In July, the town’s mayor ordered the remaining Jews to leave Wizna. A group of more than two hundred walked to Jedwabne, a neighboring town, hoping for safety. There they met an even greater tragedy. On July 10, 1941, in one of the most infamous pogroms of the Holocaust, hundreds of Jews were locked inside a barn and set on fire. Among them were the men, women, and children who had fled from Wizna only days earlier. Their cries were heard across the town before the roof collapsed.

Others from Wizna were driven into the Łomża Ghetto. Conditions there were grim. People traded their last possessions for a crust of bread. Survivors later spoke of streets where bodies lay unburied because no one had the strength to carry them. In November 1942, the ghetto was emptied. The people were pushed into trains and sent to Auschwitz. Almost none returned.

The voice of Awigdor Nelawitzky, a survivor who gave testimony after the war, describes the panic of those days. He remembered the bombing, the gangs that hunted Jews, the executions carried out at the edge of town, and the sight of neighbors being taken away. Another witness, Shmuel Wassersztejn, spoke of the cruelty that continued even after the Germans had left, recalling the betrayals by neighbors and the constant fear of death. Their words make clear that Wizna was not simply destroyed by distant soldiers but by the hands of those who had once lived alongside its Jews.

For the immigrants who had built the Independent Wizner Society in New York decades earlier, news of Wizna’s destruction must have landed like a wound that would not heal. They had created their society to hold onto memory, but now memory was all that remained. The gate of their plot at Mount Hebron became more than a marker of burial rights. It became the only surviving monument to an entire town.

When you stand before that gate today, you see more than metalwork. You see a threshold between the living and the dead, between Old World and New. You see a reminder of the families who once wrote letters across the ocean, telling of weddings and births, until the letters stopped. You see the trace of a town where children studied and merchants sold their goods, and you feel the silence left after its destruction.

The Independent Wizner Society is one of more than a thousand landsmanshaftn represented at Mount Hebron, but its meaning is profound. It speaks for a community that is gone, and yet it proves that Wizna was here. Through its gate, through its presence, memory survives.

~Blog by Deirdre Mooney Poulos

Work Cited:

Museum of Family History, “Independent Wizner Society”

https://www.museumoffamilyhistory.com/lia-sg-wizna.htm

Yahad-In Unum, “Wizna, Podlaskie Voivodship, Poland”

https://www.yahadmap.org/wizna-podlaskie-voivodship-poland/village-933

Wikipedia, “Jedwabne Pogrom”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jedwabne_pogrom

Oxford University Press, discussion of the Łomża Ghetto and deportations

https://academic.oup.com/liverpool-scholarship-online/book/37850/chapter/332333553

Testimonies of Awigdor Nelawitzky and Shmuel Wassersztejn (Yad Vashem and EHRI collections)

https://portal.ehri-project.eu

https://www.yadvashem.org