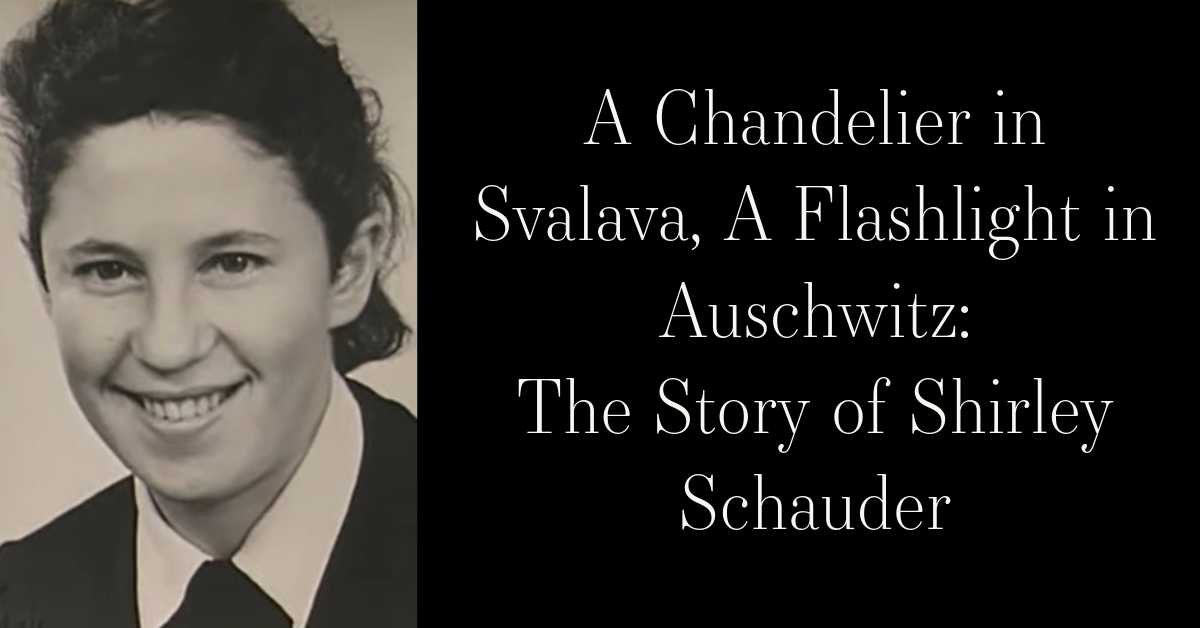

Shirley Schauder (1930 - 2025)

“I wanted them to know why I paid such a high price for being a Jew.”

Shirley Schauder, 1998

Intro

Shirley Schauder (nee Ackerman) was born on October 28th, 1930, in Svalava, Czechoslovakia, now Svalyava, Ukraine (As of March 2025). Shirley’s life can be described in three stages: It started with a somewhat pastoral childhood, followed by survival against insurmountable odds, and finally recovering by moving to the United States and reckoning with her trauma for the rest of her life. Shirley passed away on January 2nd, 2025, at the age of 94. Her passing came shortly after the lighting of the last candle of Hanukkah, a Jewish holiday that celebrates the perseverance of the human spirit. Shirley is remembered by her family for her strength, kindness, wit, and her love of poetry and painting. This post will immortalize Shirley’s life story.

Shirley Schauder, pictured with her sons Steven (Left) and Edward (Right)

Early Life in Svalava

“If you had a chandelier, you had it made.”

Shirley Ackerman at the age of 6 on her first day of school, circa 1936

Svalava, Czechoslovakia

In a 1998 testimony to the USC Shoah Foundation, Shirley described her hometown as having a Jewish community of about 3,000 Jews, which included her parents Joseph and Esther Ackerman, along with her three siblings - Helen, Oscar, and Tibor. Most of the Jewish residents of her small town were Hasidic or Orthodox, with a minority being secular. Through some research, I found that Svalava’s population in 1941 was about 8,400 total residents, many of which weren’t Jewish. As a child, Shirley loved ice skating. She recalled how her mother took her to buy ice skates one day so she could spend time with the local pharmacist's daughter, who had her father build one in their backyard. Upon seeing that homemade ice rink, Joseph Ackerman said “I can build one too”, which he promptly did with his bare hands. It’s unclear whether Joseph did it to make his daughter happy, prove he can provide for his family, or both reasons. Regardless, Shirley now had her own ice rink in the backyard, where she spent a lot of her free time.

Shirley grew up with her family in a green and white painted house, living a middle class life with five rooms, an attic, and three gardens (one of which hosted the previously mentioned ice skating rink). In her words, Shirley’s house was considered a nice one, a fact she said was cemented in the community thanks to having a chandelier. Joseph possibly worked at one of the two local shuls in their community, since Shirley remembers him counting proceeds from that week’s service. Shul, which means “school” in Yiddish, is another name for a Synagogue or a Jewish house of worship. Joseph was a dedicated Zionist and observing Jewish man, who placed an emphasis for his children to go to Hebrew school and services so they could learn Hebrew and develop their own Jewish identity.

Esther, Shirley’s mother, had three great loves in her life: Her family, needle work, and poetry. Esther especially enjoyed making unique Belgian lace designs with her needle skills. Additionally, Shirley gained her life-long love of poetry when her mother would read poems to her from a young age. Shirley recalled a funny memory of a time she performed for her community at the age of four years old. Shirly got on stage at the local community center to recite a poem Esther taught her. At the end of a, it was customary to throw chocolates on stage. Shirley, excited at being showered with applause and sweets, started collecting the chocolates, refusing to get off the stage. Joseph eventually intervened when he got on stage, picked Shirley up, and carried her off stage while shouting “The curtain didn’t close, daddy!”.

While Shirley’s childhood was mostly filled with happy memories, it also had its fair share of sad ones. In 1938, Shirley’s younger sister Helen passed away from post-surgery complications that occurred due to a burst appendix. Shirley said of her mother that despite having two young boys, Oscar and Tibor, after Helen died, she never stopped crying about her for the rest of her life. This event was the first of many tragic events that would follow for Shirley and her family.

The First Taste of the Holocaust

“You speak of identity? I never questioned my Jewishness, I questioned their sanity.”

Joseph (Right) and Esther (Left) Ackerman’s engagement photograph, circa 1927

In the same year Helen died, the Munich Agreement was signed. To appease the demands of Adolf Hitler to annex the Sudetenland or face his threats of total war, France and Great Britain elected to sign this agreement with Germany and Italy. The agreement made it so the Sudetenland, a region within Czechoslovakia with a majority of ethnic German residents, would become part of the growing Third Reich, the name designated for Germany following the rise of the Nazi Party to power. Czechoslovakia, which was not part of the agreement negotiations or signing, was pressured into accepting it by Great Britain and France. Following the devastating outcomes of World War I, including the deaths of millions of their own soldiers, Great Britain and France were terrified of the prospect of another world war, and thus wanted to do anything in their power to avoid it. After the agreement was signed, Czechoslovakia would be later divided up, with the part of it that had Svalava (Shirley’s hometown) getting absorbed into Hungary, who changed its name to the Hungarian pronunciation Svalyava. At the time, the Hungarian government was aligned with Nazi Germany, and as a result, Jews in Hungary were subjected to similar treatment as those in Germany. In her testimony to the Shoah Foundation, Shirley told a story of an encounter Joseph had with a Hungarian soldier.

While out on debt collecting errands with his sister, Joseph was approached by a Hungarian soldier, who noticed his stuffed pockets. Joseph was asked about their contents, to which he replied that they were full of money. The soldier, armed with a gun, told Joseph to “Give it to me”. Joseph, being the proud, brave, and strong man that he was, declined and asked the soldier why he should fork over his hard-earned cash. “Taxes”, the soldier said. When Joseph pointed out he didn’t owe him any, the soldier clarified the money was for “future taxes” he might owe to the Hungarian government. Joseph stood his ground, unrelenting in the presence of the armed soldier who was trying to steal his money, until his sister begged him to do so or else he’ll get shot. Joseph reluctantly gave the money to the soldier, who walked away laughing.

To Shirley’s recollection, the Czechs were nice to the Jews until 1939. Following the growing presence of Hungarian soldiers in Czechoslovakia, Jews faced persecution. Shirley remembers how Jews had to get permits to go anywhere, had to prove they were actually born in Czechoslovakia, and were regularly punished for crimes that often came from baseless rumors, such as having working ties to the black market. Joseph himself was a victim of these rumors, when one day Hungarian soldiers descended on his home, ransacking it. When asked for why they were there in the first place, the soldiers said that Joseph was suspected of dealing soap bars on the black market. When a single bar of soap was found in the Ackerman house, an item commonly found anywhere people lived, it was treated as irrefutable evidence of his guilt.

The flashlight Shirley gave to her father, Joseph, in 1943.

Still in possession of the Schauder family

In 1943, Joseph Ackerman was forcibly conscripted into the Hungarian Army to be used for forced labor. This was financially devastating for the family, as Joseph was their breadwinner, leaving them to live off whatever money they had saved. Joseph was able to gain furlough from the army to return and visit his family. During his visit, Shirley could see how visibly distressed he was. Unknown to her at the time, Joseph was experiencing firsthand what was happening to the Jews that now lived in Hungary, working in harsh conditions that regularly claimed the lives of fellow Jewish forced laborers, and witnessing the disregard the Hungarian soldiers had for the safety of said Jews. The writing was on the wall, and it spelled out a grim future for the Jews, including the Ackermans. Shirley remembered a rare display of sadness from her father, when he sang to her and her brothers “Shalom Aleichem”, while crying, the night before he had to go back. This would be the last time Joseph saw his wife Esther and his sons Oscar and Tibor. The next day, Shirley insisted on walking her father to the train station. Before he boarded, Shirley gave her father a flashlight. Joseph would hold on to that flashlight all throughout the war, crediting his survival to it. The flashlight represented hope, a shining light in dark times, and a physical connection to his family. Said flashlight is still in the Schauder family’s possession to this day.

The Toll of the Holocaust

“You knew from that day on, your life was not your own”

Oscar (Left) and Tibor (Right) Ackerman, circa 1942.

Czechoslovakia

Aged 1.5 and 1 years old respectively

In 1944, the living situation of the Ackerman family worsened. During their last Passover dinner in their home in Svalyava, the Ackermans dealt with a food shortage so bad that Shirley described the bread they ate as looking like “yellow clay”. While bread is forbidden to eat during Passover, Judaism prioritizes survival over following the commandments of the religion. This principle is called Pikuach Nefesh. Esther hosted neighbors in her house for Passover that year, and despite running low on food, insisted they take some leftovers with them. The next morning, Nazi soldiers and officers showed up on the doorstep of the Ackermans, giving them merely three hours to pack up their lives and leave their home behind. Shirley, along with her family and the Jews of Svalyava, were shuffled away to the town’s main synagogue, which was led by Rabbi Shulam Goldberger. While being led away from their homes, Shirley remembers seeing her non-Jewish neighbors laughing at them. From there, Shirley and everyone else were herded into cattle cars (a tactic used by the Nazis to dehumanize Jewish people) which took them to a brick factory. Based on the testimony of Lola Taubman, another Holocaust survivor from Svalyava, I believe the brick factory was located in Munkács, Czechoslovakia (Modern day Mukačevo, Ukraine), which was an hour away by train.

While at the factory, Shirley and others were told that the war was raging on and that placing them in the factory was for their own safety, a lie commonly used by the Nazis when taking Jews out of their homes. To maintain this lie, the Jews in the factory were not allowed to listen to the news on the radio. Shirley described the factory as a gathering spot with very little food and no real place to sleep. Esther had to build a makeshift cubicle for herself and her children out of loose bricks, which could easily fall over and crush them at any moment. Additionally, Esther was only able to pack “some salami” for herself and her kids, along with being given only a single blanket for all four Ackermans to share. On May 20th, 1944, Shirley, her family, and the other Jews in the factory were loaded again into cattle cars to be taken to their next destination.

The train ride was long and brutal, with Nazis overcrowding each car with hundreds of Jews under inhumane conditions. Accounts vary based on journey length and car sizes, with some claiming to hold 80 Jews in a car, while others claim to hold roughly 100 Jews, if not more. Shirley couldn’t remember how long the train ride was, placing it between 10 to 12 hours long, but she did remember hearing people reciting the first chapter of Tehillim, one of the five sacred books of Judaism. This chapter is often interpreted to be about a prayer asking God for protection. Oftentimes, not everyone who boarded lived to see the destination. Considering what came next, some consider them to be the lucky ones.

The train arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration and extermination camp, where Shirley would be pulled away from her mother Esther, and brothers Oscar and Tibor. This would be the last time Shirley ever saw her mother and brothers, as they would be immediately taken to the gas chambers. Esther was either 41 or 42 years old, while Oscar and Tibor were five and three years old respectively at the time of their deaths. Shirley believes she was saved due to wearing several layers of clothing, which may have successfully made her look older. Shirley was only 13 years old. It would be later when a friend of Shirley’s from back home would sort through the belongings of the gas chambers’ victims that she would find out her mother and two brothers were no longer alive.

Surviving the Camps

“...human flesh. I can still smell it. All these years, I can still smell it.”

After surviving the initial selection, Shirley was taken to be stripped of her belongings, have her head shaved, and be given a prisoner’s uniform. She described the uniform as an ugly dress. Jews arriving at the camps would be given only one uniform for their entire time there, regardless of whether it was too big, too small, or having large tears and holes in them. When the process was done, Shirley caught a glimpse of her reflection in a window, thinking “This is not me”. Her luck then extended, when she found herself being assigned to the barracks where Joseph’s sister Shari was in, with her two daughters. From that moment on, Shari would take Shirley under her wing, treating her as a third daughter. Unfortunately, Shari and other relatives of Shirley (Like Joseph’s sisters who sorted through belongings of murdered Jews) would be murdered by 1945 in Auschwitz. Shirley also remembered being forced to participate in daily roll calls, where Dr. Josef Mengele would make his selections for his next set of experiments. Dr. Mengele was notorious for the experiments he conducted on Jewish prisoners in Auschwitz-Birkenau, which are historically known to be some of the worst acts of cruelty and torture ever enacted upon human beings. The fact that Shirley had so many opportunities to land in Dr. Mengele’s clinic yet managing to avoid it is further proof to how lucky she was to survive the Holocaust.

Shirley didn’t spend a long time in Auschwitz-Birkenau, as she would be later transferred to another camp, Bergen-Belson. Shirley believed that she was being sent there to be killed, as she was never given an identification number, nor was she assigned to any specific work duty. Auschwitz was notorious for tattooing numbers on the arms of Jewish prisoners, while other camps merely had it on their uniforms. The conditions in Bergen-Belson weren’t any better than the ones in Auschwitz-Birkenau, as Shirley described being treated like a “dog”, having to sleep in the snow and marching into lines multiple times a day to be counted. While in Bergen-Belson, prisoners would be sorted into groups that would be supervised by one Jew from each group. This was another tactic used by the Nazis to divide Jews and make them turn on each other. Shirley remembered a Hungarian woman who supervised her group, describing her as “awful”. That woman would go on to survive the Holocaust and convert to Christianity, as she felt being Jewish did nothing else but paint a target on her back.

Thankfully, Shirley was able to once again evade death at Bergen-Belson, as she would be transferred to Christianstadt labor camp. There, she would work in a hidden munitions factory, making grenades. One room had women cleaning the parts, while another had women screwing the tops of the grenades. Shirley and others there had to screw the grenades fast or else they’d burn themselves on the machinery they worked with. While working in the factory, Shirley was exposed to toxic and hazardous chemicals that at some point dyed her hair red. The Nazis took precautions to keep the factory hidden from the Allied forces, such as having the commute to and from it taking between 30 to 45 minutes to complete and placing it semi-underground. The details of how the latter worked exactly are unclear, having only Shirley’s testimony to work off of, and not the name of it. Another detail about the factory Shirley mentioned was the fact that it belonged to a company that still exists to this day: Krupp. The Krupp company were one of Germany’s biggest weapons manufacturers during both world wars. Alfred Krupp, the head of the company, was an active supporter of the Nazi Regime. Similarly to Shirley’s testimony, Krupp did hide their involvement during World War II but were found out and tried during the Nuremberg Trials. These were a series of trials that took place after the end of World War II to hold the perpetrators of the Holocaust accountable for their actions.

While it was getting harder and harder for Shirley to believe she’s actually going to survive the Holocaust, there were still some rays of hope that kept her going. One very specific instance took place during a non-Jewish holiday - Christmas. On one cold Sunday evening in December 1944, Shirley was taken along with a few other women from the camp to bury the mother of a friend of hers from the camp. Since the weather was so cold and their uniforms were too thin and torn to keep warm, the Nazi officers who took them to a nearby village allowed them to carry blankets with them. While trying to dig a grave in the hard and frozen ground, the Nazi officers, who were dressed in their Sunday uniforms, went to a nearby church to attend a service. Shortly afterwards, an old woman came across Shirley and the other women. The old woman told them to wait where they are, leaving them for a few minutes before coming back with entire rolls of bread, one for each of them. In the camps, Jews would be regularly starved, only being fed leftovers from what the soldiers had to eat, often times being rotten. The old lady gave them the bread and told them “This is for Christmas”. Shirley wasn’t aware until that moment that it was the holiday season, but she would remember this moment for the rest of her life as the first time anyone treated her like a person since she arrived at Auschwitz. This would be the penultimate of the last few acts of kindness Shirley would experience before the end of the war.

Death March and Liberation

“One day, the gates opened up and in came the tanks, like angels…I remember repeating like an idiot ‘thank you, thank you, thank you’”

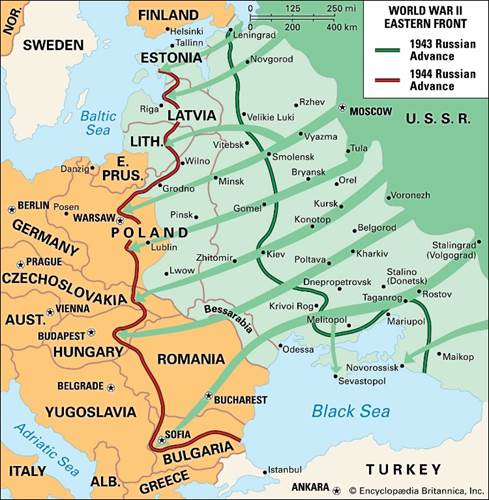

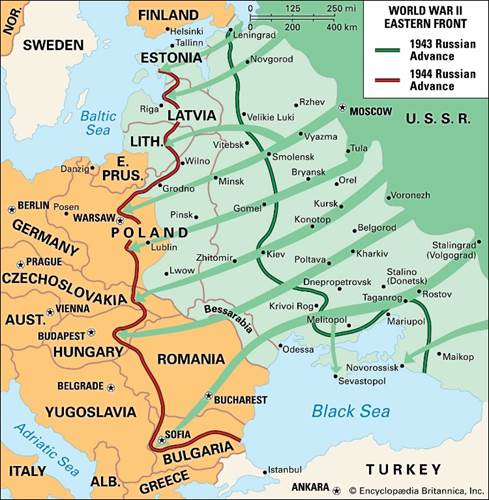

In the summer of 1944, the Soviet Red Army would make advances through Belarus to get to Poland, and later Germany. The Nazis were realizing their prospects of winning the war weren’t good, and thus started to plan how to cover up the atrocities they committed against the Jews. The Nazis viewed the Jews as living evidence, as they could testify to what happened to them and perhaps divulge sensitive information to the Allied forces. Thus, the Nazis decided to conduct death marches. In the winter months of late 1944 and early 1945, the Nazis liquidated various concentration camps, taking the prisoners on marches that were hundreds of miles long. Many Jewish prisoners were severely malnourished and sick, and coupled with the harsh conditions of a European winter in the mid 20th century, death was almost but certain for many of the Jews who were taken on these marches. In April 1945, Christianstadt was liquidated by the Nazis, and Shirley was taken on a death march to Bergen-Belson. From the rough data I was able to find online about the location of both Christianstadt and Bergen-Belsen, I found that the walking distance between them today is about 262 miles, or 422 kilometers. For reference, if someone were to start walking for 262 miles from midtown in Manhattan, New York City, they would reach about the halfway point in Pennsylvania towards Pittsburgh. Shirley remembered how at one point along the way, they walked by a village that had milk cans sitting outside. One Jewish girl stepped out of the line, possibly out of sheer desperation from being starved by the Nazis, to get her hands on some milk. An officer immediately went up to her, and without hesitation, shot her dead on the spot. At that point, the officer turned to everyone else and yelled “I told you not to move out of these lines, this should be a lesson to all of you. You move out, you get shot”. This was a harsh reminder to Shirley and everyone else that death could claim them at a moment’s notice.

Shirley also recalled hearing her name at one point during the march. When she turned to see who it was, she recognized the voice as belonging to a kid she knew all the way back from Svalyava. He ran up to her and wanted to see if she was okay. A Nazi officer yelled at the boy to get away from Shirley since she was Jewish, to which the boy replied “I know but she’s my friend”. After the officer told him again to back away, the boy whispered to her that he’ll be back and bring her some food. Unfortunately, she never saw him again. Further along the march, Shirley and everyone else were able to take refuge in various barns, which offered them a few hours of warmth after walking in the harsh European winter. Shirley and the survivors of the march would make it back to Bergen-Belsen, where she was eventually liberated by the 63rd Anti-tank Regiment and the 11th Armored Division of the British army on April 15th, 1945.

Shirley remembers seeing the British tanks coming into the camp to liberate her and the other Jewish prisoners. Shirley didn’t know much English, but she knew enough to profusely thank the soldiers for saving her. While liberation signaled the end of the war to Shirley, she’d have to survive one more challenge thrown at her by the Holocaust. Following the conversion of Bergen-Belsen into a Displaced Persons camp, many would contract Typhus, including Shirley. According to her testimony, Jews broke into a food warehouse the Nazis kept at the camp, eating whatever they could get their hands on after being starved for months, if not years. Due to their malnourished state, many Jews’ (Including Shirley) bodies weren’t able to properly process the fat content of the food they ate. Shirley claimed that about 20% of the liberated Jews of Bergen-Belsen would die of the disease. Shirley recovered from contracting Typhus, but not without suffering through 6 agonizing weeks of fevers and hallucinations. One such hallucination Shirley recalled was of seeing both her parents walking on a wall above her. Thankfully, Shirley and many others were moved from the run down and cramped barracks they slept in before the Nazis lost, and into the barracks that formerly belonged to the those same Nazi soldiers who were stationed there. Said barracks were converted into a field hospital, where Shirley was able to recover, and later leave Bergen-Belsen for the last time.

Shirley Ackerman, age 16, circa 1946

Sweden

The Road to the Land of the Free

After leaving Bergen-Belsen, Shirley would immigrate as a refugee to Sweden, which she described as “very nice and welcoming”. She was given room and board by the Swedish government through a work program, where she would have to work for a certain amount of time “in fields”, possibly agriculture. Most of this work would take place during the summer months, while throughout the rest of the year, Shirley spent by going to school to become a nurse. As part of her degree and training, Shirley would go on to work at the Gothenburg Children’s Hospital. Shirley loved her time there, treating children there but not infants. Shirley recalled the only time she worked with infants, which was when she was taken to witness a birth taking place. Unfortunately, this is all I have about her experience from that event, since Shirley fainted from what she saw and couldn’t remember much else. During her time in Sweden, Shirley also had a chance to meet with the first Prime Minister of Israel, David Ben-Gurion. She recalled how he came to meet with Holocaust survivors and how she gave a speech in his presence in Hebrew. Shirley’s fondest memory from the event was when Ben-Gurion signed multiple autographs, using her back to write them. Shirley would remain in Sweden until January 1949, at which point she would immigrate to the United States.

Before she moved away from Sweden, Shirley made a trip in 1947 to Germany to meet a very special person she thought she’d never see again - Joseph Ackerman, her father. While researching Shirley’s story, I assumed it was her who found out her father was alive and initiated contact with him, but in reality it was the other way around. After surviving the Holocaust, Joseph was back in Czechoslovakia. Following the end of the war, the Red Cross would post bulletins with names of survivors and their current locations. A friend of Joseph recognized Shirley’s name on the list, and promptly notified him about his daughter’s status. Joseph was reluctant to believe this at first. It was in 1947, after moving to Germany, that he would contact his daughter through the Red Cross. Shirley traveled there to reunite with her father after not seeing him for about three or four years. Neither expected to see the other alive ever again. During their reunion, Joseph would give back to Shirley the flashlight she gave him all those years ago, stressing to her how much it helped him survive. By this point, Joseph got remarried to a woman named Rushi (Pronounced Roo-shi). Rushi was a Jewish attorney and a holocaust survivor like her husband and stepdaughter. Additionally, Shirley described her as a very religious woman and of being jealous of her (For what reason is unclear). Rushi would unfortunately die young from cancer, although when and at what age exactly is never made clear by Shirley in her testimony, nor was I able to dig that up.

As previously mentioned, Shirley would immigrate to the United States in 1949. She had relatives living there from her mother’s side of the family as far back as the 1800s. Shirley was the first to move there, later followed by her father and other surviving relatives. As part of her immigration process, Shirley’s family had to vouch for her ability to work and study on her own while in the United States, and in the event she couldn’t do either, they would financially support her. In reality, Shirley’s family in the United States didn’t have much to their own name, let alone enough to actually support her if needed. Shirley would describe her first four years in the United States as being tough. Shirley couldn’t transfer her school credits from Sweden to the United States, so she resorted to changing her career path from nursing to accounting, finding a job as a bookkeeper. Shirley also had to support herself during this time, both working and going to school at the same time. She didn’t make a lot of money, and at times reached a point of starvation. It was after Joseph moved to the United States with Rushi and got an apartment in Brooklyn, New York that Shirley would move in with them for the next five or six years. Joseph would remain in New York City until his death on February 13th, 1989, at the age of 84.

Later Life in the United States

“He was not rich, didn’t make a lot of money, but he was a very good human being. I wanted a handsome guy”

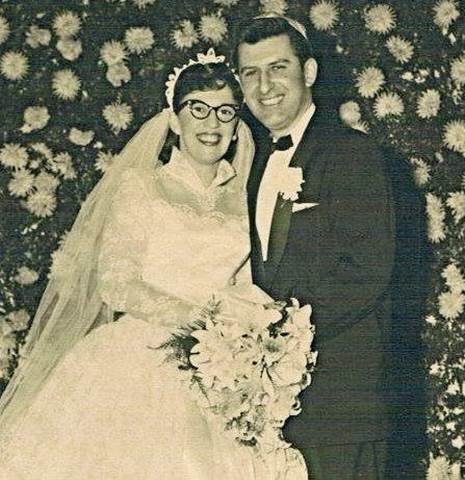

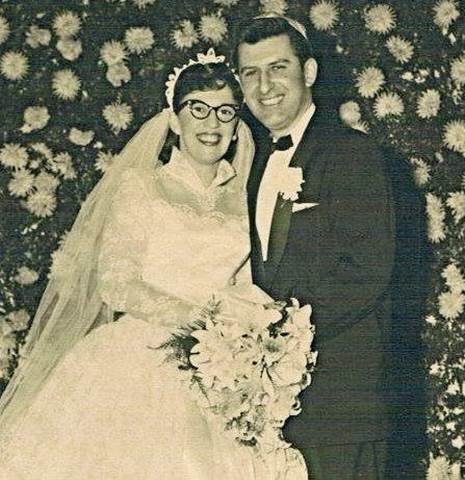

Shirley (Left) and Alfred (Right) on their wedding day

April 19th, 1959

Brooklyn, NY

It would be in her late 20s that Shirley would meet her future husband, Alfred Schauder. Born on June 13th, 1927, Alfred and his family were able to escape the Nazi regime very early on, either in 1932 or 1933. Alfred’s father worked for an English firm, which sent him to Shanghai, China, to manage an egg candling firm. Candling, as the name suggests, is a method of egg inspection where a flame from a candle is put close to it. As the persecution of the Jews by the Nazi regime got worse over time, Alfred’s father managed to convince his firm to let him stay in Shanghai with his family for the next 17 years, according to Shirley. At this point, the timeline Shirley presented didn’t add up too much, as she said Alfred joined the merchant marines, and later came to the United States when he was 16 or 17 years old and joined the army. This would roughly place him in the United States at about 1949, but if he lived in Shanghai for 17 years from 1932 at the earliest, it would mean he would only arrive in the United States when he was in his early 20s, at about 1949 or 1950. Granted, this far back, records and dates can be murky at times.

It would be on April 26th, 1958, that Alfred would meet the future Mrs. Schauder, though not in the most conventional way. On that day, which also happened to be Joseph’s 55th birthday, Shirley was on a date with another man at Hector’s Coffee Shop in Manhattan. The date would be interrupted by a friend of Shirley’s, he also happened to be on a date with none other than Alfred. Shirley said of the chance encounter that it was “love at first sight”. Both Shirley and Alfred would start dating each other for almost a year before getting married on April 19th, 1959, at the Gold Manor wedding venue in Brooklyn. Joseph would tell Shirley in jest “Now you got a handsome guy. A good guy, but not a rich guy”. Probably not too far from what my own father-in-law might’ve thought of me the first time we met. Shirley and Alfred would spend the next 37 and a half years happily married together, having two children together named Steven and Edward Schauder. Alfred, being a beloved husband to Shirley, loving father to both Steven and Edward, and devoted grandfather, would pass away on September 18th, 1996, at the age of 69.

Shirley (Left) and Alfred (Right) at a Bar Mitzvah, circa 1994

While raising both Steven and Edward, Shirley felt it was important for her children to have a strong connection to their Jewish identity, same as her father felt about his children. Shirley sent both her sons to a Yeshiva. A Yeshiva is commonly a Jewish school that places an emphasis on religious studies, but the one that both Steven and Edward went to also had exceptional secular studies included. Unfortunately, the experience in the Holocaust left a permanent mark on her, which still surfaced when Shirley was a mother. In separate interviews I had with Steven and Edward, they described Shirley as a complex woman and as an overprotective mother, at times showing up at their schools to make sure they were okay and eating enough food. Additionally, Shirley was very reluctant to talk to her children about her experience in the camps, even having had a few trauma related outbursts. Steven and Edward slowly pieced together that their mother was a Holocaust survivor, and always knew that their mother’s love for them was unwavering and strong enough to move mountains. Edward remembered his mother’s sharp wit and deadpan sense of humor, while Steven commented on her volunteer work with political activism and her Jewish community.

Shirley also carried her love of painting and poetry throughout her whole life. She would often write poems for the birthdays of her grandchildren and spent some free time expressing herself through painting. One painting in particular that both Steven and Edward have mixed feelings about is a portrait of a clown. As children, the clown would unsettle them, but as they grew up, Steven and Edward felt less and less scared of it, even noticing interesting details. In his interview, Steven told me about how he noticed that the clown looked very much like his mother, except for the eyes being his fathers. Neither sons, nor Shirley, ever fully understood why she used those facial details while painting the portrait. Different interpretations came up from time to time, mostly about Shirley’s emotional state or her connection to her husband, Alfred. That being said, it wasn’t the only clown portrait she ever painted. Shirley had a personal interest in clowns, with her son Steven sharing that she saw them as “Sad people who make people happy”.

Conclusion and Legacy

“When you listen to a witness, you become a witness”

Elie Wiesel

Shirley Schauder’s grave (Right) prior to her tombstone consecration, circa 2025

Shirley’s final resting place is beside her beloved husband, Alfred.

In 2024, Shirley moved to Florida to be closer to her children and grandchildren. Despite being in her 90s, Shirley still managed to stay lucid and active, with Edward sharing with me a video of her effortlessly bending over to touch her toes ten times. Meanwhile, I struggle with more than 5 push ups and I’m a man in my early 30s. As her health deteriorated, Shirley would receive care from Alpert Jewish Family Service and MorseLife Palliative Care. Hanukkah of that year would be the last holiday she celebrated with her family, passing away not too long after the last candle burned out on January 2nd, 2025, a poignant ending to a remarkable life. Despite all the hardship she experienced, and the insurmountable odds she beat, Shirley managed to create a large and loving family that still remembers her, and hopefully, was able to finally find peace. Her funeral was held at the Mount Hebron Cemetery in Queens, New York, and the shiva was held in Palm Beach Gardens in Florida.

Researching Shirley’s life made me think a lot about an art installation at the Museum of Jewish Heritage in Manhattan, New York. The installation consists of several large boulders, each having a tree grow out of them. Shirley’s life was a testament to the strength of the human spirit, and a shining example of survival, perseverance, and love. Shirley never lost her sense of humor, nor did she fail to show her family her devotion to them and how much she loved them. Shirley’s story is one of many out there. While not uncommon for survivors like Shirley to be reluctant to talk about their experience in the Holocaust (Either due to survivor’s guilt, a sense of shame, or something else entirely), she still managed to muster up the courage to record a testimony, thus helping to create a lasting memory of her existence on this earth.

May Her Memory Be Blessed

יהי זכרה ברוך.

~Blog by Adam Har Shemesh

I would like to extend a special thanks to the following:

- Shirley’s sons, Steven and Edward Schauder, who agreed to talk to me and provide insight into their mother’s character, along with images of her belongings.

- The USC Shoah Foundation for making a digitized version of Shirley’s testimony from 1998 available.

- Deirdre Poulos of the Legacy Foundation at Mount Hebron Cemetery for connecting me with Steven Schauder, who then helped connect me with his brother, Edward.

Bibliography

- USC Shoah Foundation – Shirley Schauder Testimony

- https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/vha39235

- 45 Aid Society

- https://45aid.org/location/svalyava-czechoslovakia-now-svaljus-ukraine/

- Munich: Prologue to Tragedy

- By J. W. Wheeler-Bennett, published 1965 by Viking Press

- The Extermination of the European Jews

- By Christian Gerlach, published 2016 by Cambridge University Press

- Appeasement and the Road to War

- By David Armstrong and Elizabeth Trueland, published 2006 by Hodder Gibson

- Holocaust Encyclopedia

- https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/timeline-event/holocaust/1933-1938/munich-agreement

- https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/neville-chamberlain

- https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/oral-history/david-dudi-bergman-describes-bar-mitzvah-during-deportation-by-cattle-train-from-auschwitz-to-plaszow

- https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/deceiving-the-public

- https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/josef-mengele

- https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/subsequent-nuremberg-proceedings-case-10-the-krupp-case

- https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/death-marches

- https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/timeline-event/holocaust/1942-1945/liberation-of-bergen-belsen

- My Jewish Learning

- https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/pikuach-nefesh-the-overriding-jewish-value-of-human-life/#:~:text=One%20of%20the%20most%20basic,demands%20preservation%20beyond%20anything%20else

- Portraits of Honor – Lola Taubman

- https://www.portraitsofhonor.org/survivors/lola-taubman

- Yad Vashem

- https://wwv.yadvashem.org/yv/en/exhibitions/communities/munkacs/index.asp

- https://www.yadvashem.org/holocaust/about/final-solution/deportation.html

- Holocaust Historical Society

- https://www.holocausthistoricalsociety.org.uk/contents/naziseasternempire/warsawghettogrosaktionsummer1942.html

- Chabad – Tehillim Chapter 1

- https://www.chabad.org/library/bible_cdo/aid/16222/jewish/Chapter-1.htm

- BibleRef

- https://www.bibleref.com/Psalms/1/Psalms-chapter-1.html#:~:text=Psalm%201%20proclaims%20truths%20echoed,arising%20from%20sin%20and%20disobedience.

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

- https://www.ushmm.org/learn/holocaust/the-many-legacies-of-elie-wiesel

- https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/vha39235

- Britanica

- https://www.britannica.com/event/Eastern-Front-World-War-II/Stalingrad-the-turning-point-in-the-East-July-17-1942-February-2-1943