Story Summary:

The Independent Ekaterinaslaw Society, formed by Jewish immigrants from the Ukrainian city of Ekaterinoslav (now Dnipro), embodied the resilience and communal spirit of those fleeing imperial antisemitism and pogroms in the early 20th century. In New York, the society provided crucial mutual aid, healthcare, funeral benefits, and community events, while preserving ties to their hometown. After the Holocaust devastated the Jewish population of Ekaterinoslav, the society transformed its mission to remembrance, establishing burial plots and memorials at Mount Hebron Cemetery in Queens. Though the organization no longer meets, its legacy endures in preserved records, headstones, and shared histories, serving as a testament to the power of memory, identity, and solidarity across generations. ~Blog by Deirdre Mooney Poulos

From Ekaterinoslav to Queens:

The Story of the Independent Ekaterinaslaw Society

In the industrial heart of what is now Ukraine, the city once known as Ekaterinoslav—today called Dnipro—was home to a thriving Jewish community with deep religious, cultural, and commercial roots. Founded in the late 18th century along the Dnipro River, Ekaterinoslav grew rapidly under the Russian Empire. By the early 20th century, Jews made up a significant portion of the city’s population, with dozens of synagogues, yeshivas, charities, and Jewish-owned businesses forming a tight-knit and vibrant urban life.

Despite its energy and cultural richness, the city was not immune to the growing tides of antisemitism. Jews in Ekaterinoslav faced discrimination under imperial law, periodic pogroms, and a volatile political climate. The early 1900s saw increased hardship for Jewish residents due to restrictive quotas on education and employment, targeted violence, and waves of political upheaval. This combination of opportunity and oppression drove thousands to seek new lives in the United States. Among them were families who would later form the Independent Ekaterinaslaw Society in New York—a mutual aid organization dedicated to helping fellow immigrants navigate their new world while preserving ties to the old one.

In neighborhoods like the Lower East Side, Brownsville, and eventually the Bronx and Queens, former residents of Ekaterinoslav built new homes but never forgot their origins. The Independent Ekaterinaslaw Society, like many landsmanshaftn (mutual aid societies based on towns of origin), provided critical services to its members. These included health and funeral benefits, small loans, and assistance with job placement. Most importantly, the society maintained a strong sense of community identity by organizing holiday celebrations, social events, and securing burial plots for its members.

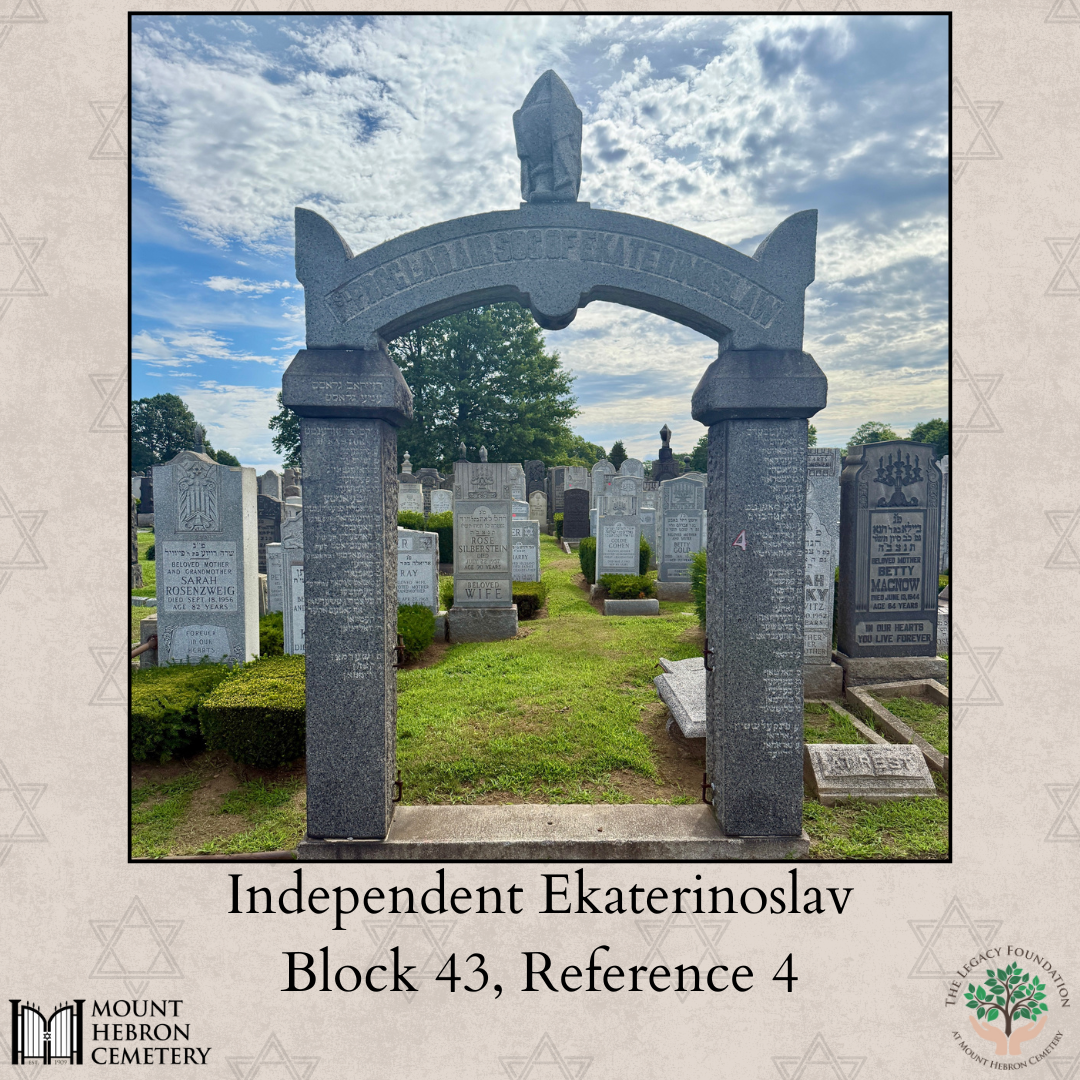

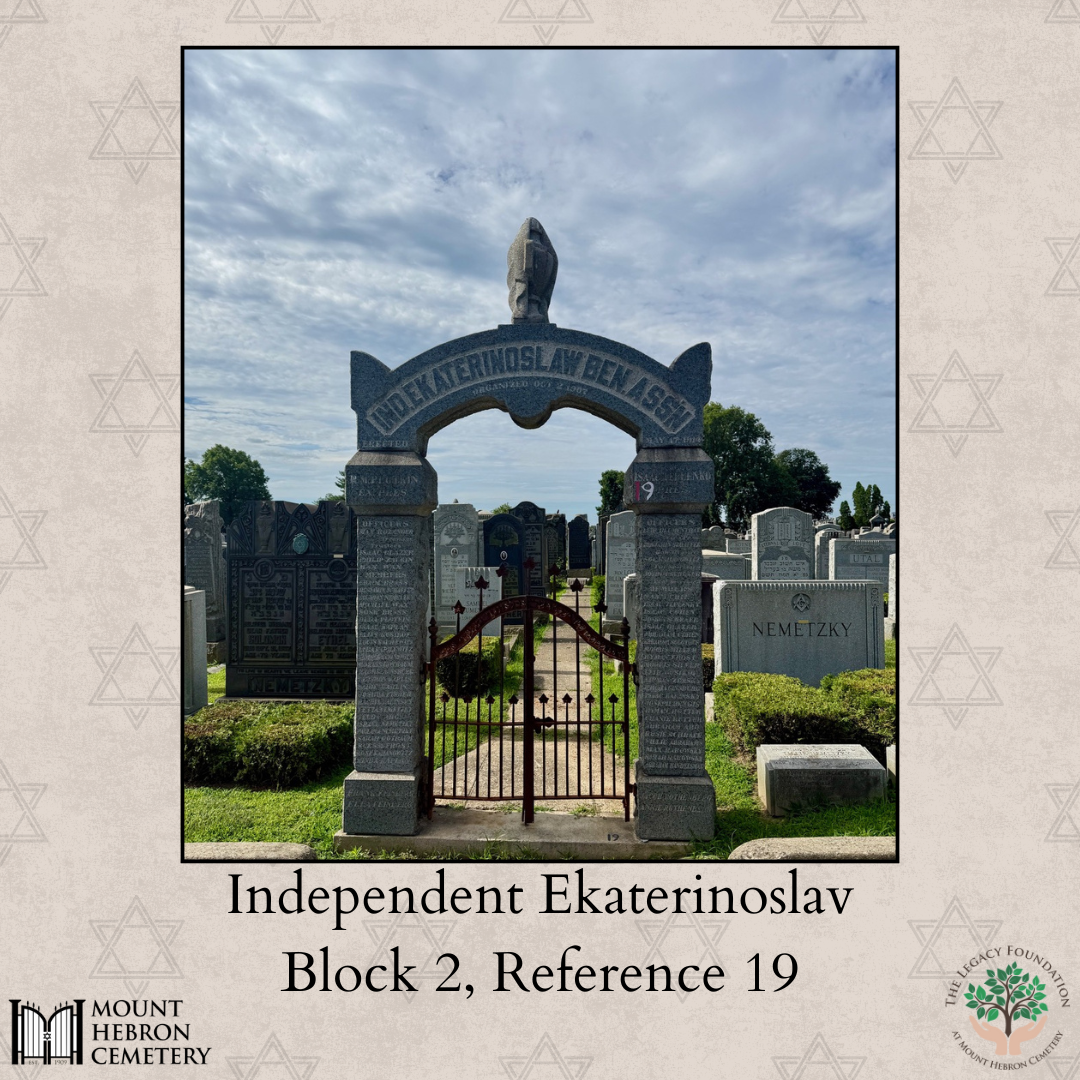

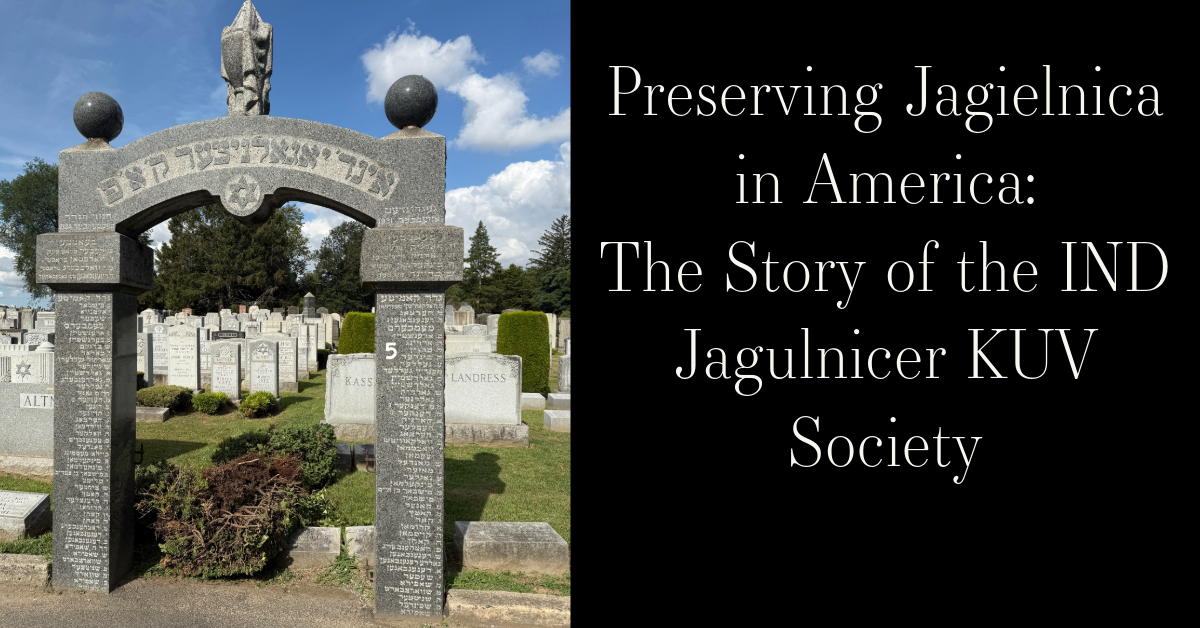

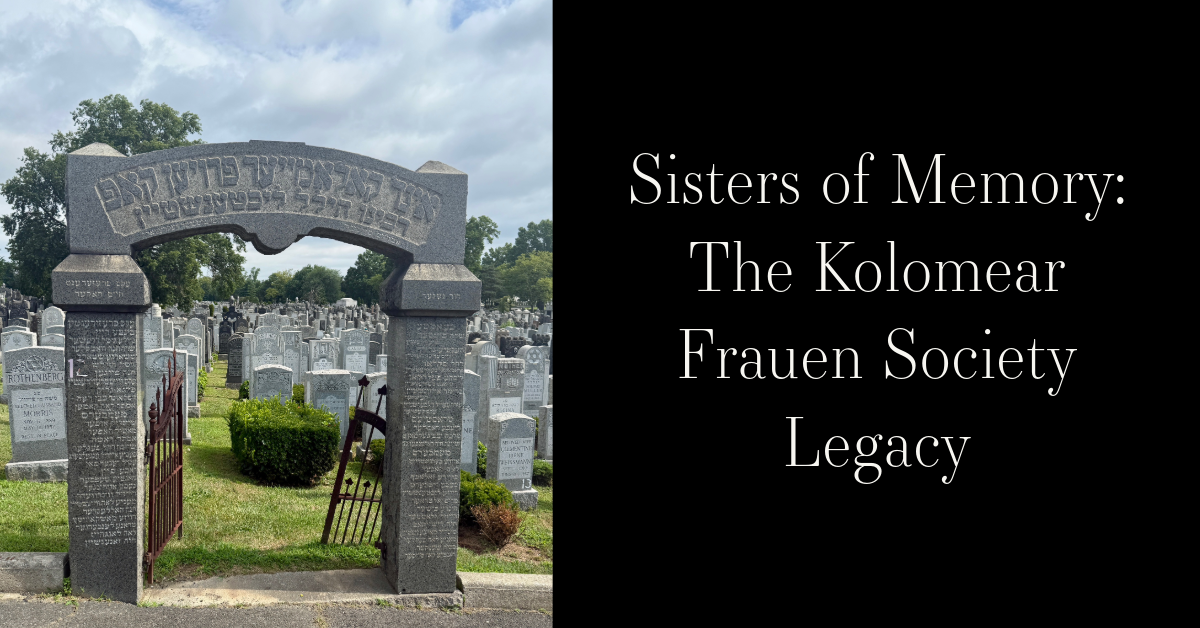

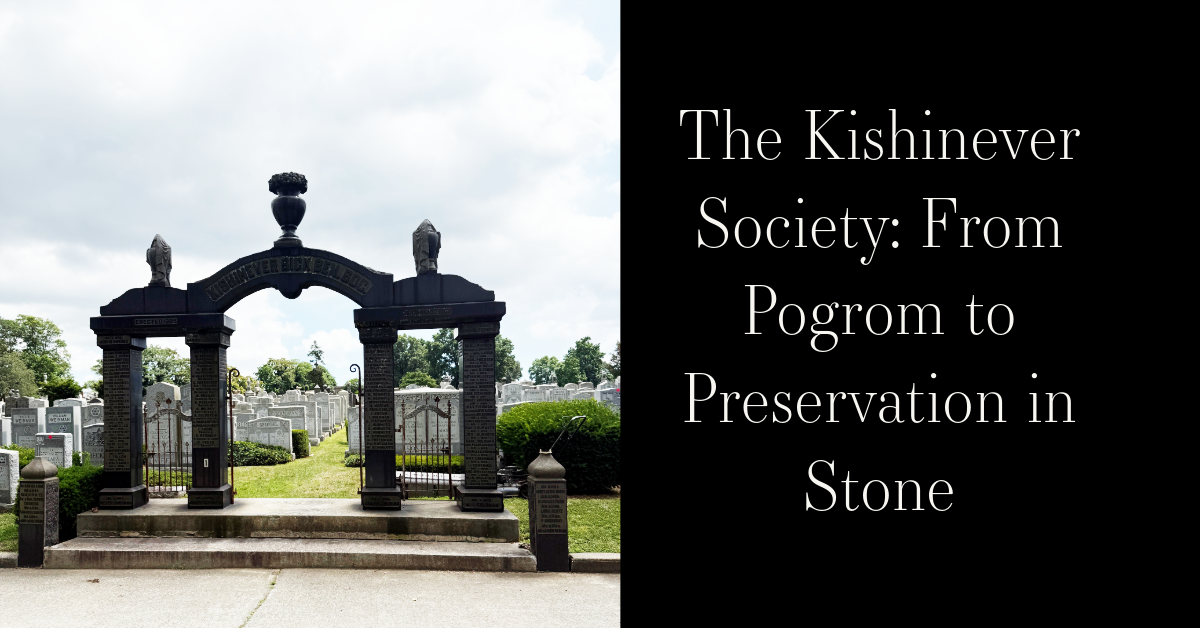

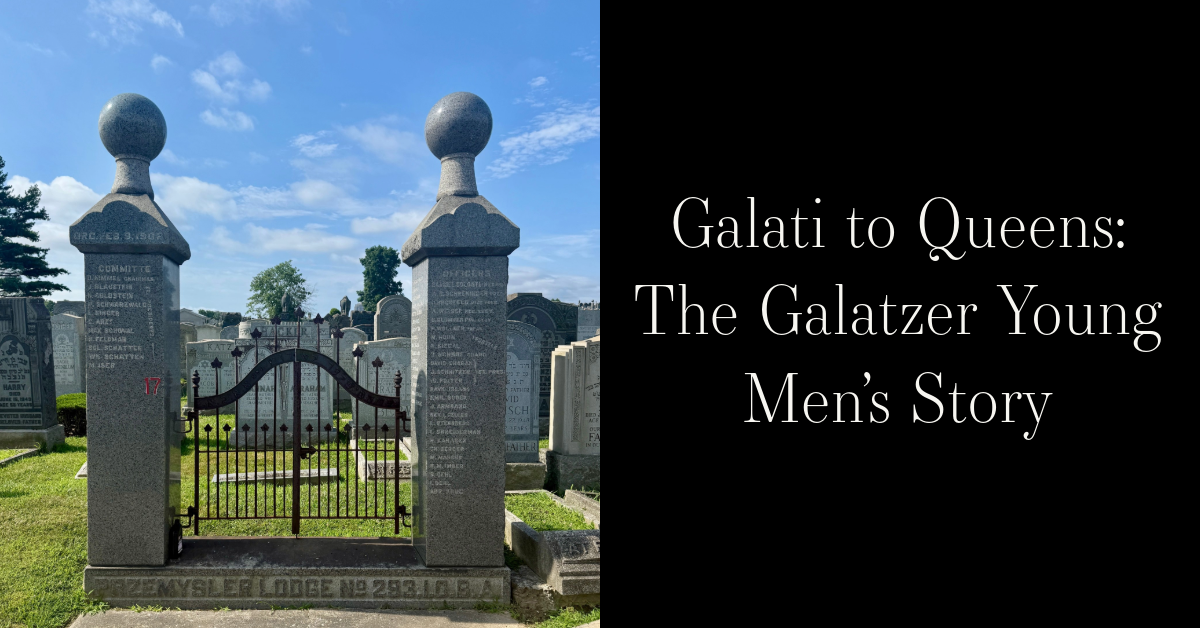

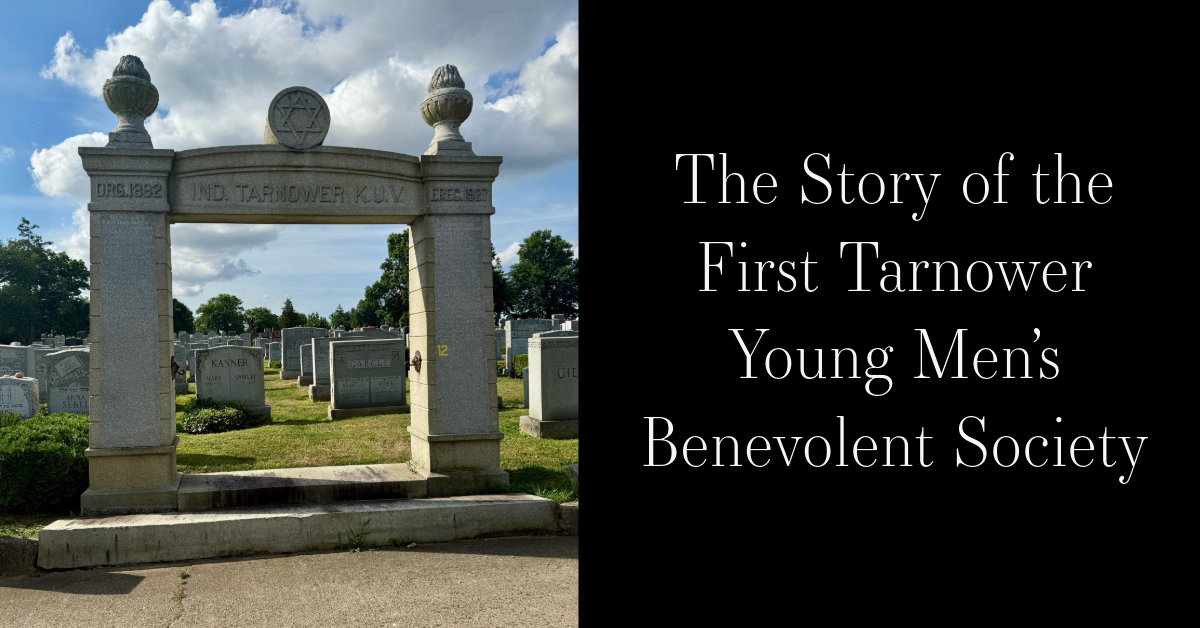

Mount Hebron Cemetery in Flushing, Queens, is home to the burial section associated with the Independent Ekaterinaslaw Society. Here, among neat rows of headstones inscribed with Hebrew and Yiddish, the name of Ekaterinoslav is preserved in stone. These burial grounds became sacred repositories of communal memory—final resting places that reflected both continuity and loss.

While their lives in America were marked by resilience and reinvention, members of the society could not escape the tragedies that struck their hometown. During World War II, when Ekaterinoslav was under Nazi occupation, its remaining Jewish population suffered catastrophic losses. Mass shootings, forced labor, and deportations decimated the once-thriving community. Most of those who stayed behind were murdered in the Holocaust.

For the descendants of immigrants who had long since resettled in New York, the news arrived in waves—disbelief, mourning, and silence. The Independent Ekaterinaslaw Society’s mission of support evolved into one of remembrance. Society members erected memorials, preserved records, and held Yizkor (memorial) services for the victims of the Shoah. Their burial plots in Queens served not just as physical spaces for the dead, but as emotional sanctuaries for the living.

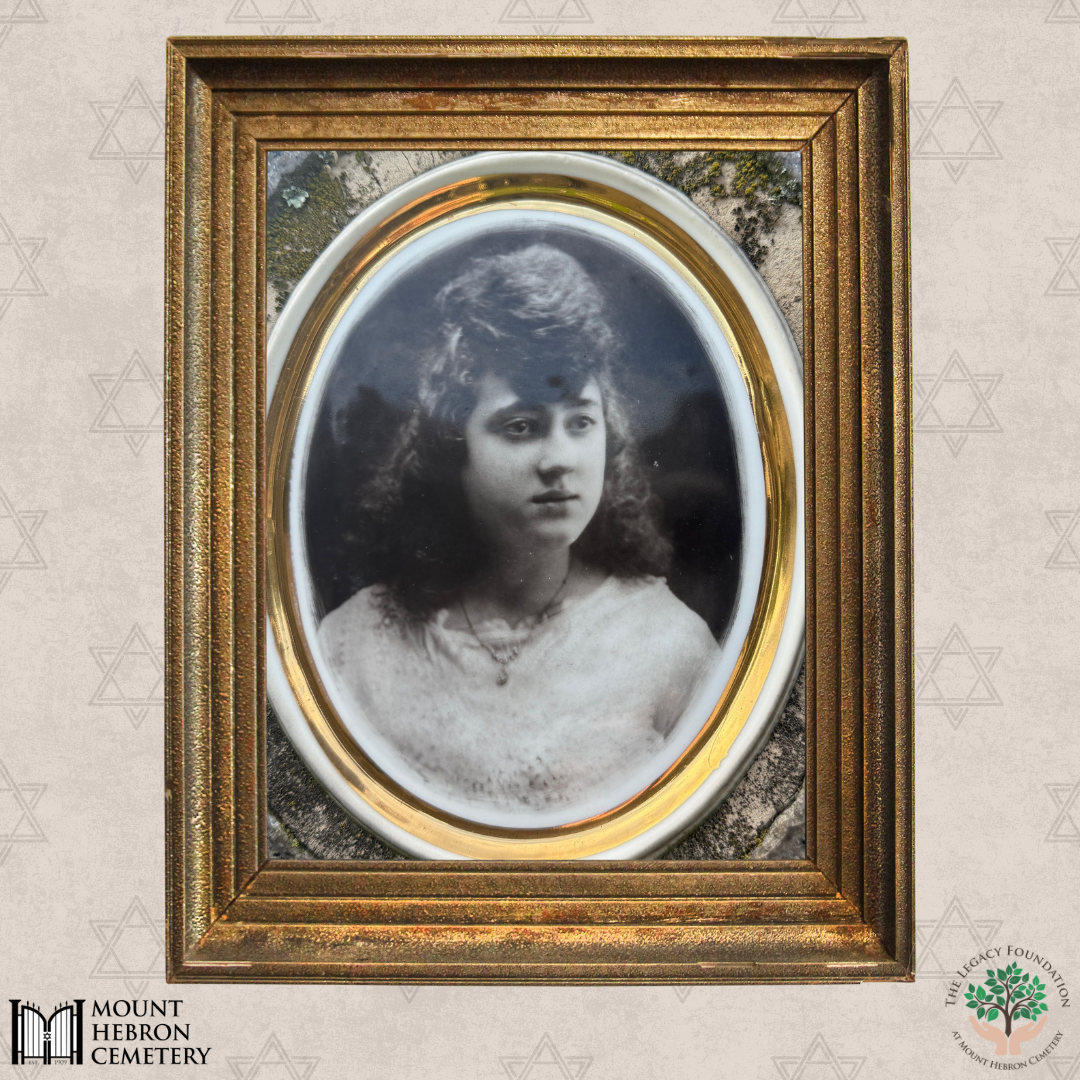

Today, even if the society itself no longer meets, its legacy continues through the stone markers that remain, the genealogical records preserved in cemetery files, and the stories shared among families. These remnants allow future generations to trace their origins, understand the histories that shaped their ancestors, and honor a city that once thrived on the banks of the Dnipro.

The story of the Independent Ekaterinaslaw Society is not only one of migration and memory, but also of communal strength. In the face of exile, assimilation, and genocide, this group of immigrants chose to remember—through tradition, through solidarity, and through stone.

~Blog by Deirdre Mooney Poulos

Work Cited:

Yad Vashem – The World Holocaust Remembrance Center

https://www.yadvashem.org

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM)

https://www.ushmm.org

JewishGen KehilaLinks – Dnipro (Ekaterinoslav)

https://kehilalinks.jewishgen.org/dnepropetrovsk

Jewish Virtual Library – History of Jews in Ukraine

https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/history-and-overview-of-ukrainian-jewry

Center for Jewish History – Landsmanshaftn Collections

https://www.cjh.org

YIVO Institute for Jewish Research

https://yivo.org