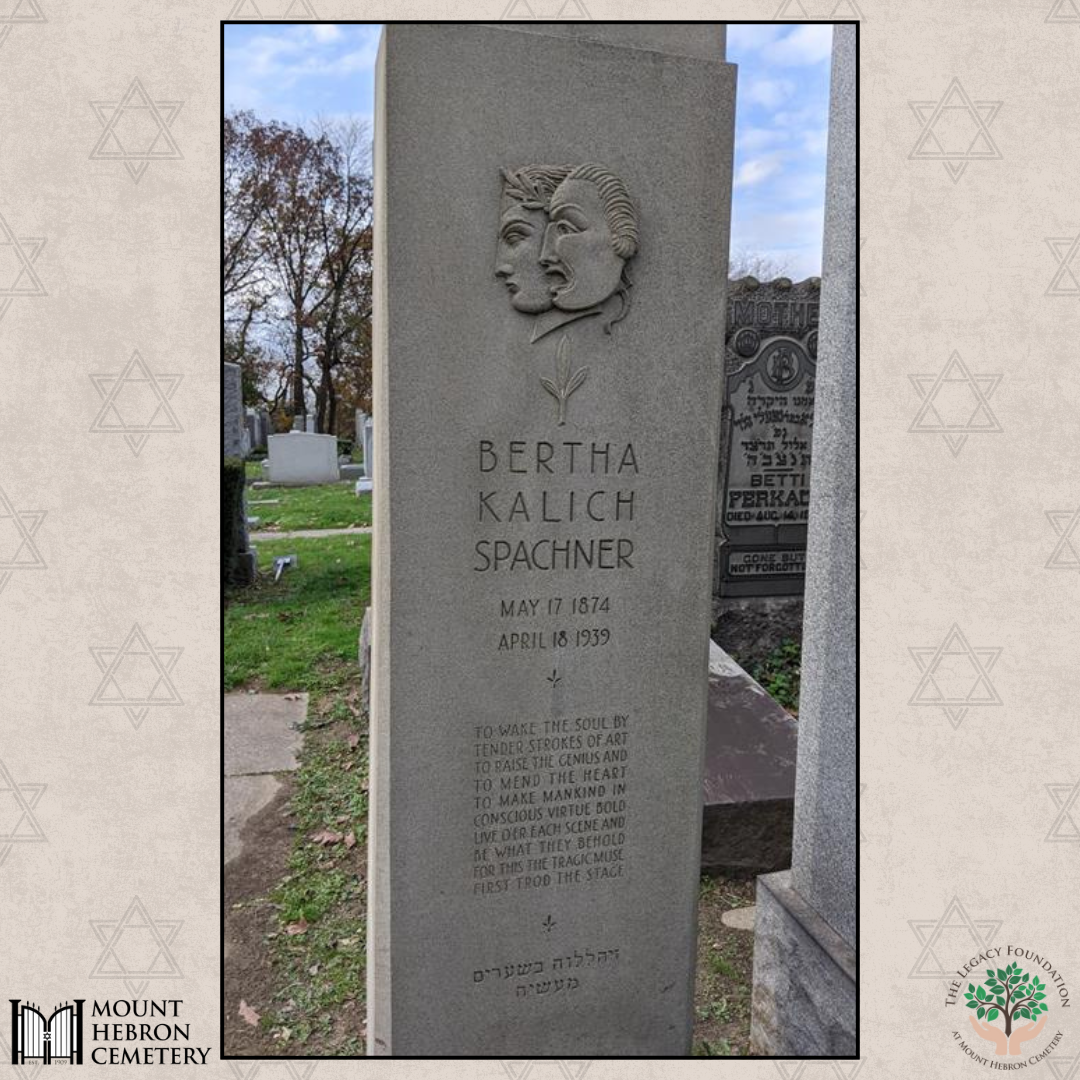

Bertha Kalich: The Jewish Bernhardt

Bertha Kalich (AKA Kalish) was born Beylke Kalakh on May 17, 1874 in Lemberg, Galicia. Bertha was an only daughter, born ten years after her parents married. Bertha’s father and grandfather were brush manufacturers, while her mother designed and created clothing for actresses. Growing up, Bertha was exposed to the performing arts since her father loved to play the violin for the family and her mother often took Bertha to the Opera. Bertha’s parents had longed to see Bertha as an actress on stage.

Bertha described her childhood in her memoir stating, “The entire family thought only of me. All day they talked about Beylkele (Bertha), as though nothing else in the world existed…Every corner of my home was filled with love for me. Everyone’s eyes laughed and beamed when they looked at me. I was the radiant star of the house. It was at grandmother’s request that I used to go with my father and grandfather Friday nights and Saturdays to the synagogue. …Those Sabbaths and holidays were wonderful.”

When Bertha was 8 years old, she attended the opera "Carmen," on several occasions after which time she was singing the arias. Once Bertha attended Goldfaden’s productions in Lemberg’s Garden Theatre, she decided then and there that that she could sing as well as the actors and actresses that she saw. Inspired, Bertha went home, put on her mother’s clothes, and performed a "theatre-piece" for the family. Bertha’s love for singing was greater than all of her other interests.

A director from the German theater who had heard about Bertha and observed her perform, agreed to teach Bertha piano and declamation. He later gave Bertha a job performing in a one-act play at a big hotel and helped her get into a music school. At the age of 11, Bertha attended the Lemberg Conservatory where she began dreaming of becoming a Polish actress. Two years later, Bertha’s parents developed monetary issues. Bertha had to leave the conservatory and return home to assist the family for the next three years. Once her parents were financially secure, Bertha found a job in the chorus at the Skarbek Polish theatre. There, Bertha met Regina Prager and Jacob-Ber Gimpel. Bertha would later become one the first actresses at Gimpel’s Yiddish theatre in Lviv. Bertha went on tour and performed throughout Eastern Europe once her contract ended.

Bertha began working in the choir of a Polish theatre and she played roles in "La Traviata," and in the opera "Mignon." At age 14, Bertha enrolled in a performing arts school where she learned acting, public speaking, German mimicry, and piano. Bertha played "the daughter" in the German one act play, "I Marry Off My Daughter."

Bertha next began working for a theatre which showcased opera performances, dramas, and operettas. Once Bertha started being offered small roles, the other chorus members, who were Christian, started feeling jealous of Bertha. One day, Bertha met Gimpel in the theatre and explained her predicament. He tried to persuade Bertha to work with him in his theatre stating that she would gain nothing by staying there. Gimpel felt that the more that Bertha would distinguish herself, the more persecution would prevail. Gimpel suspected that the other performers may conspire to poison Bertha and he therefore assured her that she would be safe if she joined his theatre. Gimpel explained that a move to a new career would open doors for Bertha and Bertha would always have unlimited opportunities to succeed. Despite Gimpel’s persuasion, Bertha decided to remain in the Polish theatre. When the time came for Bertha to move on, she joined Gimpel singing in the chorus and playing small roles. When Gimpel’s leading lady quit, Bertha enthusiastically stepped into her new role.

Avraham Goldfaden soon hired Bertha to perform in "The Tenth Commandment." Her performance was a big hit with the theatre-goers. After Bertha’s third season with Goldfaden concluded, she was offered a new job by an impresario from the Romanian National Theater. Bertha accepted the job and she soon had a part in an operetta entitled, 'The White Lady." She then became an imperial singer. When she was 17, Bertha performed in the Imperial Cabaret, in Budapest, Hungary. In 1890, in Lemberg, Bertha performed with the actor, Asher Zelig Schorr, in Dr. Y.L. Landau’s "Hordus and Miriam."

In 1890, Bertha married Leopold Spachner, whom she had met during her conservatory days. The couple had two children, Arthur, a son who died in early childhood, and a daughter named Lillian.

One of the singers in the Romanian Theatre warned Bertha not to drink any water there and not to smell the flowers that people sent her. The man had heard that the other singers were extremely jealous of Bertha and he suspected that they may plot to poison her. When he explained this to Bertha, it evoked terror in her heart.

Mr. Edelstein, from New York’s Talia Theater arrived in Bucharest. He went to speak with Bertha imploring her to accompany him to America and work in one of his theaters alongside the familiar actors that she had previously performed with. Due to Bertha’s lingering fears about continuing to work in that toxic setting, Bertha immediately decided to break her contract with the Theatre. A short time later, Bertha and Mr. Edelstein departed from Romania along with Bertha’s parents and Bertha’s husband, Leopold Spachner.

In 1899, Bertha performed in Kobrin’s play, The East Side Ghetto in the Thalia Theatre. Starting with this play and the others that followed, Bertha became more and more famous. She spent time searching for the best plays to act in prior to accepting roles. After each of these plays, Bertha became a more and more skilled actress who became loved both by the public and by the critics.

Bertha worked for Yakov Ber Gimpel, the Yiddish theatre director, and became his leading lady. Her first appearance was as a young girl in a scene from "Shulamis.” Later, Bertha had an acting role in "A Millionaire as a Beggar."

Bertha traveled to Hungary where she had several solo performances and then performed in the synagogue’s Yom Kippur choir. The organist who accompanied her, persuaded the other performers to hear Bertha sing since he understood that Bertha was seeking full time employment. Although everyone was impressed with her talent, Bertha was not hired due to antisemitism.

The day before Bertha was scheduled to perform for the King of Romania, a group of actors from the Romanian National Theatre arrived at the venue where Bertha was set to perform. Unbeknownst to her, an anti-Semitic faction had been planning to pelt Bertha with onions once she appeared on stage. Fortunately, this did not occur since the members of the hate group had surprisingly enjoyed Bertha’s singing. Therefore, they dispensed with the onion idea and instead threw flowers at Bertha. At the same time that the hate mongers were planning their nefarious deed, a different group of people had concocted much more sinister plans. The theater director, Mr. Barman, and the theater’s leading ladies, had been conspiring to murder Bertha while she was preoccupied with greeting a group of Romanian aristocrats. Once Bertha discovered that her life was in danger, she safely escaped with Josef Edelstein, a manager, her parents and her husband. Edelstein had long been impressed with Bertha’s talent. He personally sought her out and convinced her to relocate to America.

Bertha was motivated to come to New York due to her artistic ambition combined with a desire to escape the difficult circumstances in Europe. In 1896, Bertha and her family left the country through Bremen and arrived in the USA, where she performed several plays at the Thalia Theater (a prominent theater in New York), where Edelstein was the manager. After Bertha’s close call, a rumor had circulated that Bertha had died, and there was even an obituary printed in the newspaper.

At the Thalia Theatre, Bertha acted in classic Jewish plays like The Two Kings, Perele, and Shulamith. After a few months, Bertha accepted leading parts in Othello, Romeo and Juliette, and Hamlet. Bertha worked hard at the Thalia Theatre during all the seasons and she later joined the main troupe. In the year 1899, Bertha became one of the Thalia Theatre directors together with Spachner, Kessler, Mogulesko, Feinman and Simovitch.

At this point, the Yiddish theater started producing more serious plays in addition to translations of Shakespeare and modern European dramatists. Bertha’s career began to flourish. One of Bertha’s more outstanding performances was when she starred in Gordin's The Yiddish King Lear. Bertha did an equally wonderful job performing in a play which depicted ghetto life, such as The East Side Ghetto, The Truth, and God, Man, and the Devil. Bertha was considered the leading dramatic actress of the Yiddish theater during these ten years of Bertha’s career. Bertha’s early performances helped establish Bertha as a talented dramatic actress and laid the foundation for her successful career in both Yiddish and later, English-language theatre.

After her contract at the Thalia Theatre ended in 1905, Bertha abandoned the Yiddish stage and embarked on a significant career transition to the English-language stage. Bertha caught the attention of many Broadway producers, who, overlooked Bertha quickly caught the attention of Broadway producers, who, overlooked the language barrier, and sought to hire Bertha only because of her extraordinary talent. Bertha realized that her accent was a hindrance to her career and she worked diligently to decrease her Polish accent.

Bertha’s initial English-speaking appearance was at the American Theater where she played in the title role of Victorian Sardou's Fedora, on May 22, 1905. This performance apparently shocked everyone. A review by an incredulous critic stated "here was a Yiddish actress from the Bowery precincts," wrote one incredulous critic, "wearing Paris gowns as though to the manner born, and as regal and distinguished looking as Duse or Re-jane!"

Bertha a positive reception from the audience. While Bertha was a highly respected actress in the Yiddish theater, her success on the English-language stage helped to continue to elevate her reputation as well. By moving into a larger market, Bertha hoped to gain more visibility. Bertha knew that the English-speaking audience was growing, and she wished to engage with these people. Bertha realized that by making this transition, she would be offered new roles and artistic challenges that would assist her in diversifying her performances.

Bertha appeared in a few notable Hollywood films between 1914 and 1918, working with such popular producers such as Lee Shubert and Arthur Hopkins. From 1916- 1918, Bella began accepting roles in silent films as well. In 1915, Bertha continued to perform in English, but she returned to the Yiddish stage regularly.

Regarding her crossover to the English stage, in 1931 Bertha’s English director, Harrison Gray Fiske, wrote " Madame Bertha Kalich made her modest, experimental performance in English as the heroine of Sardou’s Fedora. Her acting was for me a completely unexpected revelation. I heard a voice with a remarkable timbre, powerful, sonorous, that completely mastered every level of drama. Oh, what a voice!

"She worked some months on a role in Monna Vanna which she went over with me each day, mainly in order to lose her Polish accent, to obtain a genuine English pronunciation of the words and to remove every trace of exotic notes and the like. And when she performed, everyone was astounded by her authenticity in English … She played the role with dramatic effect … and many people felt that a great new talent had come to the stage. … in a short time, she spoke English well enough and clearly enough, that she was trusted with a major role in Sardou’s Fedora.”

Other audiences, however, did not find Bertha so appealing due to her ethnicity and her accent. The Boston Transcript commented that "In nothing but an exotic part, where she is either a woman of foreign birth or a strange creature doing strange things can the American public accept her." Eventually, even Minnie Fiske, Bertha’s language tutor, found it challenging to locate roles suited to Bertha’s unique talent. Therefore in 1910, the two stopped working together.

Mr. Gray Fiske, whose wife, Minnie Maddern Fisk, was one of the famous actresses of the English stage, offered Bertha a contract to act on Broadway resulting in Bertha becoming one of the most important stars of the English stage. She played in literary plays and also in melodramas—in MacKaye’s Sappho and Phaeon, in Jacobi’s The Riddle: Woman, in Zola’s Térèse Raquin, in Gordin’s "Kreutzer sonata."

Regarding Bertha’s transition to and performances on the English stage, I.B. Bailin writes: ‘In certain circles, people criticized her (Bertha) for abandoning the Yiddish theatre … her first performance in “Fedora” made an impression. Her second performance, in "Monna Vanna", was even more successful. The critics in the English theatre press sang her praises. For a period of nearly thirty years, Bertha was mentioned in the theatre columns of the English press. She played in “The Unbroken Bride”, in “The Riddle: Woman”, and in Bernard Shaw’s version of a part of “Trebitsh’s Jitta’s Atonement.” But her role in "Kreutzer Sonata" was the best that I have seen anywhere."

Bertha later performed in several plays which were not successful, mainly plays that failed in New York. She had success performing in English one-act plays in vaudeville, earlier in New York, later throughout the provinces. In September 1915, Bertha once again returned to the Yiddish stage and gave several performances with David Kessler during the opening of the Second Avenue Theatre. In 1915 Bertha appeared as Katiusha Maslova in Tolstoy’s “Resurrection.”

Bertha acted at a Yiddish theater in Philadelphia. She started giving speeches after her performances, reminding theatre goers that they should be thankful that she, the famous Kalich from the American stage, made an effort to perform for them in Yiddish.

Rose Shomer, a playwright, describes Bertha’s religious beliefs: “Above all, she loved to speak about religion and the Bible. Deep in her heart, she was a believer, a religious person, and she believed in a personal God who watched over her and protected her from harm ...”

Bertha discussed the stunning costumes she looked forward to performing in. “In the whole play I had not one scene where I wore beautiful clothing? It is unheard of that I, Bertha Kalich, who is known on Broadway for her artistic way of dressing, should not have the opportunity once in the play to appear in a beautiful dress ... I will not perform in the play. Do you hear? You write a scene for me to appear in beautiful clothing.’

While performing in the Soul of a Woman (1928), Bertha caught a cold which affected her eyesight. Despite three operations, she became increasingly blind and officially retired from the stage in 1931. She did not believe that the doctors could help her. But she did believe that God could help her.

In 1932, in honor of her fortieth jubilee and theatre service- the theatre profession gave Bella a 'testimonial' exhibition in the Yiddish Art Theatre. In 1934, the English theatre profession gave Bertha a second testimonial in the Vanderbilt Theatre in New York. She made occasional benefit and testimonial appearances, the last of which was a performance at the Jolson Theater on February 23, 1939.

Rumshinsky wrote regarding Bertha’s sight: "It is remarkable that when she was already completely blind, she used to come to the rehearsals and shine every night on the stage, she lit up every corner. We were all ready to see a frightfully sad personality, but her resounding "Hello" with her lovely smile used to make everyone forget about her closed, darkened eyes.”

Afterward, because the situation in the American theatre changed so much that there was no more place there for Bertha. She had no alternative but to return to the Yiddish stage, and regarding her return to Yiddish theatre, Leon Kobrin writes: “She was half-blind, but she hoped that she could be cured and would again perform on stage. 'I still feel so young in spirit and in body'—she said—'I can still give so much to the world. I know that my God will not forsake me. Do you see, Rose, what I have here?' I keep this with me wherever I stay or go. From her handkerchief, she took out a small white piece of paper and unfolded it. On the paper was written in English, in big letters so that she could read it, an excerpt from David’s prayer: 'God is my shepherd, I lack nothing ... I fear no evil, for you are with me.”

I.B. Bailin recounts that in 1937 or 1938, he visited Bertha who stated, "People have already completely forgotten about me. Years ago, so many people applauded me with such delight ... clapping their hands, sending air-kisses ... I had my fill of them then, too much. Now I have nothing."

Bertha made significant sacrifices for her acting and singing career. Joseph Rumshinsky writes: "She sacrificed her personal life for the stage. She neglected her own life. In her earliest years, she even dismissed the ordinary and extraordinary compliments with which she was showered because she saw and heard only theatre and thought only about studying, besides her roles, also languages, and everything that had a relation to theatre. She even sacrificed her nearest and dearest, even her one child. Madame Kalich’s daughter [Lilian] was also sacrificed on the altar of her mother’s art."

At this point, the Yiddish theater started producing more serious plays as well as the translations of Shakespeare and modern European dramatists. Bertha’s career was flourishing. One of her more outstanding performances was in Starring in Gordin's The Yiddish King Lear. Bertha was equally effective performing in realistic play which depicted ghetto life, such as The East Side Ghetto, The Truth, and God, Man, and the Devil. Over these ten years of her career, Bertha was considered the leading dramatic actress of the Yiddish theater.

Bertha quickly caught the attention of Broadway producers, who, overlooked the language barrier, and sought to hire Bertha only because of her extraordinary talent. Bertha realized that her accent was a hindrance to her career and she worked hard to decrease her Polish accent. Bertha’s initial English-speaking appearance was at the American Theater where she played in the title role of Victorian Sardou's Fedora, on May 22, 1905. This performance apparently shocked everyone. A review by an incredulous critic stated "here was a Yiddish actress from the Bowery precincts," wrote one incredulous critic, "wearing Paris gowns as though to the manner born, and as regal and distinguished looking as Duse or Re-jane!"

Manager Harrison Grey Fiske, a manager who later recalled Bertha’s Broadway debut as a "wholly unexpected revelation," signed the actress to a five-year contract. Fiske sent Bertha for English language tutoring by Minnie Maddern Fiske. Bertha played successfully on Broadway for many years. She appeared in several plays such as: Monna Vanna (1905), The Kreutzer Sonata- In English (1906), Therese Raquin (1906), Marta of the Lowlands (1907), Sappho and Phaon (1907), The Unbroken Road (1908), and Cora (1908).

Audiences were not as taken about Bertha Kalich's appeal since her ethnicity and her accent posed large hurdles for them. The Boston Transcript commented that "In nothing but an exotic part, where she is either a woman of foreign birth or a strange creature doing strange things can the American public accept her." Eventually, even Minnie Fiske, Bertha’s language tutor, found it difficult to find roles suited to Kalich's unique talent, and in 1910, the two stopped working together. Bertha began acting for various producers including Lee Shubert and Arthur Hopkins, among others, and made several movies between 1916 and 1918.

The first Yiddish play to be translated, adapted, and staged on Broadway was Jacob Gordin’s Di kreytser sonata [The Kreutzer Sonata]. This play was adapted by Jacob Gordin from a novella by Tolstoy. Gordin’s play opened in 1902 to Yiddish audiences at the Thalia Theatre. The Kreutzer Sonata had been written for and starred Bertha Kalich. It ran in Yiddish for over 300 performances and it was considered one of Gordin’s most financially successful plays. Bertha had the role that she had originated on the Yiddish stage.

Strikingly tall, with a deep, resonant voice and expressive face, Bertha noted that she took on 125 different roles in seven languages during the course of her career. Although she was a skilled singer, she preferred roles that were serious dramas to operettas and musical melodramas. Bertha was an advocate for better quality Yiddish plays as well as higher artistic standards.

Bertha’s later stage roles included performances in Jitta's Atonement (1923), adapted from German by George Bernard Shaw, Magda (1926), and The Soul of a Woman (1928). After performing in The Soul of a Woman in 1928, Bertha Kalich's health declined, particularly her eyesight, and she became gradually blind. Bertha’s eyesight was affected by a cold in the late 1920s. Despite multiple operations, her vision declined.

Bertha officially retired from the stage in 1931. She made occasional benefit and testimonial appearances, the last of which was a performance at the Jolson Theater on February 23, 1939. She published a book of her memoirs during her retirement.

Although Bertha had three operations, she continued to lose her eyesight until she finally became blind. Although Bertha retired from the stage in 1931, she continued to make occasional appearances. These appearances took place at benefit events held in Bertha’s honor; these events demonstrated the theatrical community's high regard for Bertha’s legacy.

As Bertha’s health continued to fail, she kept recording scenes from Avrom Goldfaden's historical plays for "The Forward Hour" on WEVD radio. However, due to Bertha’s poor health, she needed to do extensive rehearsals for even short parts.

Bertha’s last public appearance was on February 23, 1939, Bertha attended a benefit event at the Jolson Theater, where she recited the final scene of Louis Untermeyer's poem "Heine's Death". Bertha Kalich died at the age of 64 on April 18, 1939, following several weeks of treatment for a stomach ailment. Her death occurred in Queens, New York. While Bertha’s funeral was attended by 1500 people, it was considered a smaller turnout given her status within the Jewish community. Bertha Kalich’s remains were interred in the Theatrical Alliance in Mount Hebron Cemetery in Flushing.

~Blog by Renee Meyers