Herta Munk Zauberman: Saved by a Split-Second Decision

This is the story of Herta Munk Zauberman, a concentration camp survivor. Herta was born on August 26, 1924 in Dziedzice, Poland. Her parents were Julia and Isador Munk. Herta was an only child. She was born in the home of her grandparents, then her father built her family a home in town.

Isador was a businessman who owned a small department store. Her grandfather owned a business which exported grass from Belgium and Holland that was used for making mattresses. When her grandfather died, Isador took over his business. Julia went into business with Isador.

Herta lived in Czechowice, which was a town with 250 Jewish families. Her home was somewhat isolated from the other homes. Herta attended a Polish Public school where she was the only Jewish child in her class. She went to Hebrew school twice a week in the afternoon with the rest of the Jewish children in town. When Herta finished grade school, she attended Gymnasia High School in Bielsko, Poland. Herta remembers going on a family vacation and right after the family came back, the War had broken out and Herta never attended school again. Isador had a brother in Germany. The Munk family heard when Kristallnacht occurred. Herta stated, “We knew about it, but it had nothing to do with us.”

Shortly after the war began, the trucks started rolling in. The Germans took Herta’s father and her uncle to work in town scrubbing the sidewalks “to humiliate and degrade them”. Soon, the Jews were forbidden to go out during certain hours and to certain stores. Isador’s business was closed immediately. At that time, the Jews needed show food cards which employed people received, to obtain food. Herta had a job painting furniture but lost thejob. An acquaintance gave Herta a bag of candlewicks to knit socks. Herta and her mother knitted day and night. Her grandmother helped as well. At night, Herta walked to many of the villages that had farms, since many of the farmers were willing to exchange beans, and sometimes bread for those socks. Herta’s aunt also worked by selling socks which she knitted. The SS caught Herta’s aunt holding a piece of bread. She was taken to a ghetto and was never seen again. About this business, Herta stated “people had to find ways to survive so they took many risks.”

The Munks had to leave their home and were sent to Oswiecim, a city with mostly Jews where food was easier to obtain. The family lived in an apartment here for six months. When they were permitted to return home, Herta’s uncle, parents, grandmother and Herta moved into her grandparent’s house.

In June 1942, the Munks and other Jews in the village were told to come to a certain destination which turned out to be a warehouse. Here, the Jews were first selected and then separated. Herta’s close friend also came to this warehouse. She had gotten married and recently had a baby. During the selection, the SS attempted to take her baby away. However, Herta’s friend would not let the men have her baby and she clutched the infant to her breast and ran from them. This woman and her baby were eventually sent to Auschwitz.

During this selection, Herta’s entire family were sent to the “wrong side” except for Herta. Herta tearfully recalled the last time Herta saw her family at the train station where they were waiting for a train on the platform. She saw her mother and her grandmother but she did not know where her father was. And then they were gone.

Herta was sent to Sosnowiec for a week. In this city, Herta fortunately passed another selection. In Susnowiec, Herta was one of fifty women and girls who were sent to a work camp in Germany. This group was lucky because their Lager Fuhrer was a decent woman. Even so, the women had to work very, very hard. The food in Susnowiec was a little better than in other places and the women themselves were also allowed to cook.

When Herta was in the Bolkenhain Camp, she had a job weaving fabric for parachutes. She worked mostly at night on 12–15-hour shifts. Herta was with a group of 50 teenaged girls. who slept together in bunks. Sunday was a day off work when the women could wash their clothes. This group of girls were very close friends in the camp. Herta stated that she is still in touch with the survivors from this camp.

Herta was transferred to the Merzdorf Camp, which was run by the same weaving company as in the Bolkenhain camp. She remained there for about 8 months. The women’s job was to drag balls of flax and use a pitchfork to throw them into large bins containing chemicals, remove the balls and load them on trucks. Herta noted that this was extremely hard work which caused the workers eyes to burn and their skin to itch. The girls slept in beds in a barn and their food consisted of bread and soup. Herta said that in Merzdorf, she did not feel starved.

Herta was placed in the Grinberg Camp where she lived for 8 months or a year. This camp also had a large weaving factory. There were 2,000 women with 1,000 women sleeping n each room. In this camp, the food was insufficient and the girls suffered from regular beatings. Herta was beaten twice. Herta stated that “In Grinberg, life was much, much, much harder.” The women wore rags with wooden clogs on their feet when it was very snowy. They worked in factories with other Germans who were their supervisors. The Jewish Lager Fuhrer pushed and hit the girls. Once a month, a group of SS men came to this camp for a selection. The girls had to strip naked and walk in front of the men. In Jan 28, 1945, a big group of women arrived in Grinberg from Auschwitz. The women were separated into groups of 1,000. One of the groups were sent in another direction which turned out to be toward Bergen Belsen.

Herta described going on a Death March where they were “walking, walking, walking, crying, freezing, stop crying, starving, and then repeated.” The girls were hit with the butts of the German’s rifles. Whenever a girl needed to stop walking, be it for bodily functions or for any reason, they were immediately shot. Each day, there were 4, 5, 9 or 11 people killed. Herta recalls freezing and starving on this March. If any of the girls attempted to escape, the Germans made the entire group line up and then they shot every other girl. The girls had to walk between 20 and 25 Kilometers every day and they slept outside huddled together in the freezing cold. Occasionally they were put in a barn to sleep. Herta remembers always feeling starved. The girls were each given one cup. It was never filled with food because most of it spilled out when the liquid was poured in. Herta stated, “There is no bigger punishment than hunger. No killing, no hitting, no beating is as painful as hunger.”

The girls were transferred to Hambrecht’s Camp for several months. Most of the girls there were sick. Herta also became ill with diarrhea, typhus, and dysentery. In Hambrecht’s, there were Appells. Herta described the Appellplatz (roll calls) and said the women had to run to the courtyard and were counted for hours while it was snowing. These Appells typically took place before the sun came up. Herta’s illnesses and starvation resulted in extreme weakness. She only able to stand with a friend on each side of her holding her up. One day, after the Appellplatz, Herta fainted and was taken to the infirmary. When Herta woke up, she saw the two sisters that she had become friendly with taking care of her and helping her. One of the sisters told Herta that she remembered Herta because Herta had shown kindness to her in Auschwitz and helped her locate clothes to wear. The sister helped Herta to the point that when she left Hambrecht’s Camp, she was able to walk again. Herta has maintained her relationship with the sisters to this day.

Herta told a story which she found upsetting about one of her acquaintances. One day in Hambrecht’s, the girls were told to put anything personal that they still owned into a pile. Herta’s acquaintance hid a little picture of her family that she refused to add to the pile. Someone informed on this girl and she was punished by having to stand for three days without shoes in the snow. She survived the War but continued to have pain and difficulty ambulating. Herta maintains contact with this woman and confirms that the woman’s condition has marginally improved.

As the group continued the Death March, they passed through the village of Domazlice. It was a nice day and peasants were outside with barrels of bread, soup, and milk for the inmates. Herta stated that seeing all that fragrant food after being starved for so long, “felt like heaven; like I died.” The girls immediately started running frantically toward the food and desperately grabbed whatever they could get their hands on. Just as fast, the SS began shooting their guns in the air and then pushed the peasants and their food far out of access of the mob of starving women. Herta’s friend, who had difficulty walking, managed to escape with a companion in Domazlice. She was later liberated by the Americans.

The women continued marching. At one point, they passed a farm and discovered a pile of spoiled Sugar Beets. The ladies ran into the mountain of sugar beets and they were promptly shot on the spot. Herta did not follow the women since she was always afraid of reprisals. There were some women who ate the beets but were not shot. These women died during the night and also on subsequent nights as a result of Refeeding Syndrome, where the bodies’ ability to process food became severely compromised due to their prolonged starvation.

One day, an army was passing by and the group had to get off the road. The women went to sit down on a hill in a little forest with many bushes. A group of women got up and walked away to relieve themselves since diarrhea was rampant. Soon, the women who were sitting with Herta on the hill heard loud screaming and yelling. The SS men assumed that they were escaping and began yanking these women back to the hill by the hair. One woman had her hair pulled and then the SS man, still holding her hair, swung her against a tree until her brains popped out of her skull.

In March, many members of the Wehrmacht arrived. The Wehrmacht consisted of old women who were part of the SS. Herta felt that these women were much more vicious than the men. A large group of black American prisoners passed by and they were peeling their beets. Herta ended up walking in the back, which Herta felt was a very bad place to walk since the SS were on both sides of the inmates and the SS in the back were able to watch everyone. The women marched passed an area where there were peels from sugar beets on the ground. Herta was starved, and without thinking, bent down to pick up a peel. The SS woman sped up until she was standing directly behind her. As Herta picked up her head to straighten up, the SS woman forcefully cracked the butt of the gun into Herta’s face. Herta’s lip and lower chin were split open and Herta began bleeding heavily. She was so dizzy after being struck, that a friend had to help her walk.

As the group continued their march, they arrived at a small village near the Czech boarder. Herta’s friend suggested that they both escape. Herta told her friend to escape by herself since she does not like to take chances. They passed an old Church on the side of the road. Herta liked Churches since she used to go with her nanny. Since she felt a sense of comfort, she made the split-second decision to go with her friend and hide from those in the Death March. Herta and her friend noticed a high wooden fence with a little gate across the road and they ran over to it. Herta pushed the gate and there was a cemetery as well as a little shack and they quickly ran inside. There, they saw a table. Herta looked through the window and saw the SS woman who hit her. The woman and Herta locked eyes. Herta remembered thinking, “Now we are lost.” Then both women quickly scurried under the table. After just a few minutes, they heard screaming and yelling outside. Apparently, some of the women saw them escape and followed them. Herta and her friend quietly remained under the table until night fall. Then they decided that they would come out but it was too dangerous to go in the same direction that their transport went in. So, they walked in a different direction, through the cemetery and they came to a mountain. The girls began climbing.

When they climbed down, they noticed a tiny light in the pitch darkness. It was a barn. They went up to the barn and knocked on the door. When someone answered, the girls said, “We are Polish, we escaped and we need shelter.” This was the home of a family from Poland. They took Herta and her friend in their home and gave them food and shelter. In a few days, the father came to them and said, “We found out you are Jewish and you cannot stay here because there is an SS office in the main house.” The girls knew they had to leave. However, both of their feet had swollen to epidemic proportions and they were unable to stand up. The man allowed them to stay in his home until they recovered. When the girls could walk and felt better, the man said that his sons would take them to the forest and at the end of the forest was a highway which is only used for the German Army Transport. He advised them to only cross on their bellies and not walk across. The girls got across and they were soon on the other side of the highway. The Polish family told them to look out for a village with red roofs. They soon realized that this whole village had red roofs. They were in the Czech underground! Before long, they saw men running toward them. They picked Herta and her friend up and took them two different homes where they were taken care of and nursed back to health.

It was still very dangerous where Herta was since there were Germans in the mountains, even after Liberation. All around them, Czech people were being shot. Herta would have liked to remain with the family since she knew she had no longer had a family. However, she decided to go to Israel. The farmer she lived with said there was another young Jewish girl in the village from Herta’s transport. The girl visited Herta and they both decided to go to Israel. When she was stronger, the farmer took the girls with the horse and buggy to a town and an American truck picked them up. They went to Bratislava, which was a point where people go when they wish to go to different countries. Once Herta and her friend got there, two young men approached them and asked, “You are Jewish?” They said “yes.” The men hugged and kissed them and said that they are so happy since they thought that no Jewish women survived the war.

All the survivors Herta met wanted to go to Israel. However, because of an English blockade, they could not get through. Herta stayed in an army barracks called Rittenberg. The city of Salzberg gave these people some land with which they built a hugh village for people on a mountain. They collected money and the men then purchased 24 pre-fabricated homes. Herta was employed doing office work in the UNRRA. The worst thing for Herta was the loneliness. She was very scared about her future and did not know where to go or what to do. Herta still longed to go to Israel. But that longing ended once Herta found out that her only relative there, an aunt, had died of breast cancer. So now, she had no relatives or anyone she knew there.

Herta knew Felix, her future husband, since he worked in the office and was one of the leaders in his DP camp. All the young Jewish singles knew each other and had a pleasant life in the DP Camp. Friday night, the women and girls cooked dinner and they invited the men to come. The American Jewish soldiers also came every Friday night.

Herta and Felix bonded over a love of music. They were allowed into the Opera Houses in Salzberg for free. They also attended Mozart recitals together. After a 6-month courtship, Herta and Felix decided they wanted to build a home together. In June 18, 1946, they became Felix and Herta Munk Zauberman.

After her marriage, she was contacted by someone who knew her mother’s cousin and her husband who lived in Bielsko. They wrote to Herta that the homes of her parents and her grandparents should be sold. In February 1947, Herta decided to go back to Poland while Felix remained in Salzberg. Herta was able to sell the houses. When Herta was still in her old neighborhood, she decided to visit her gentile neighbors across the street. The Munk family had been very friendly with these neighbors and Herta adored playing with the neighbor’s children because she was an only child. When the neighbor saw her, the first thing she said to Herta in Polish was “Are you still alive?” This statement hurt Herta deeply since she grew up with the couple’s children. Herta expected a warm hug but instead was shocked by the neighbor’s cold and insensitive remark that she thought Herta had already been murdered.

While Herta was still in the neighbor’s home, she casually looked around and she noticed her great grandparents’ candlesticks. Then she saw a silver napkin holder from her parent’s home as well as three of her mother’s silver forks. The neighbor gave Herta the candlesticks and told Herta “a story” that the Germans pilfered the remaining pieces in the silver wear set. After Herta left this home, she walked through the neighborhood and discovered that her childhood boyfriend had survived. Herta started her trip back to Salzberg and she was suddenly caught on the Czech-Polish border. At that time, this travel was very dangerous since Poland was occupied by Russia. The authorities did not find anything suspicious with Herta but only let Herta go after a week of sitting in a Prison on the border. Herta reunited with Felix in Salzberg. On December 23, 1948, Herta and Felix arrived in New York where they have been living in Lake Success, New York.

Herta stated that until 10 years ago, she had constant bites on her left arm. She bit herself all the time because of all the suffering she lived through. Herta was asked, how did she survive? Herta said that she made one decision to escape the week before the end of the war. That was probably the right decision because she probably would not have survived the week after. Herta learned that the week after she escaped, a tremendous number of women died or were shot. Herta thinks that possibly because she was a little passive, and not pushy that she survived. Due to all the suffering Herta personally witnessed and experienced, she has a hard time with religion in her life although she is emphatic that she is proud to be Jewish.

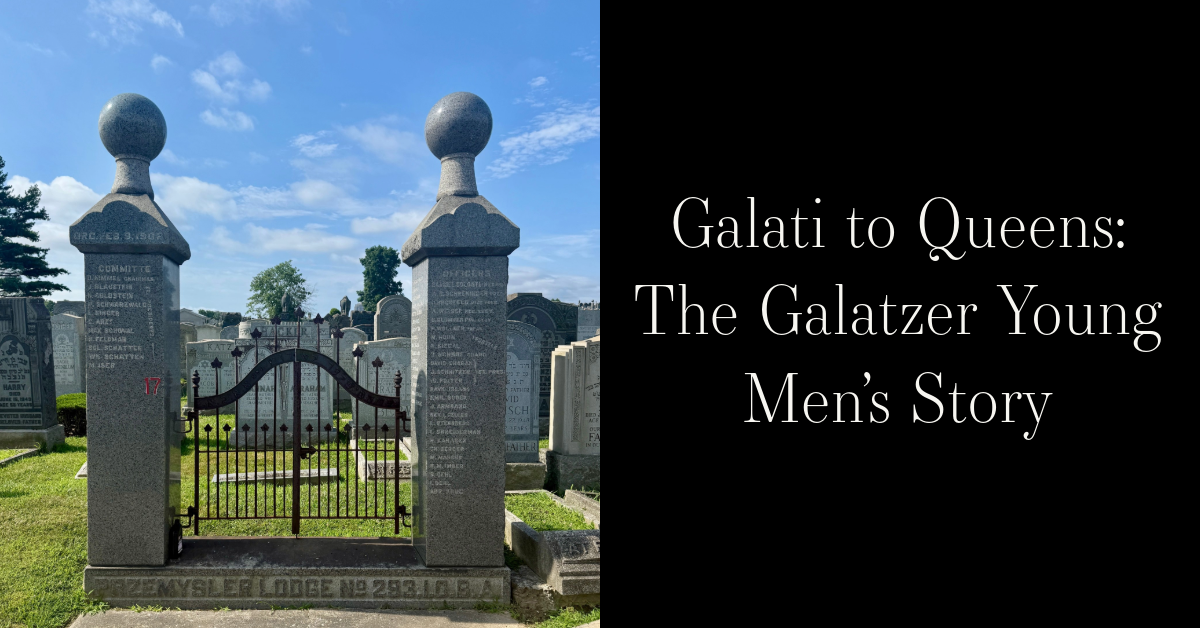

Herta Munk Zauberman passed away on August 21, 2022 at the age of 97. She is buried in Mount Hebron Cemetery in New York.

~Blog Written by Renee Meyers