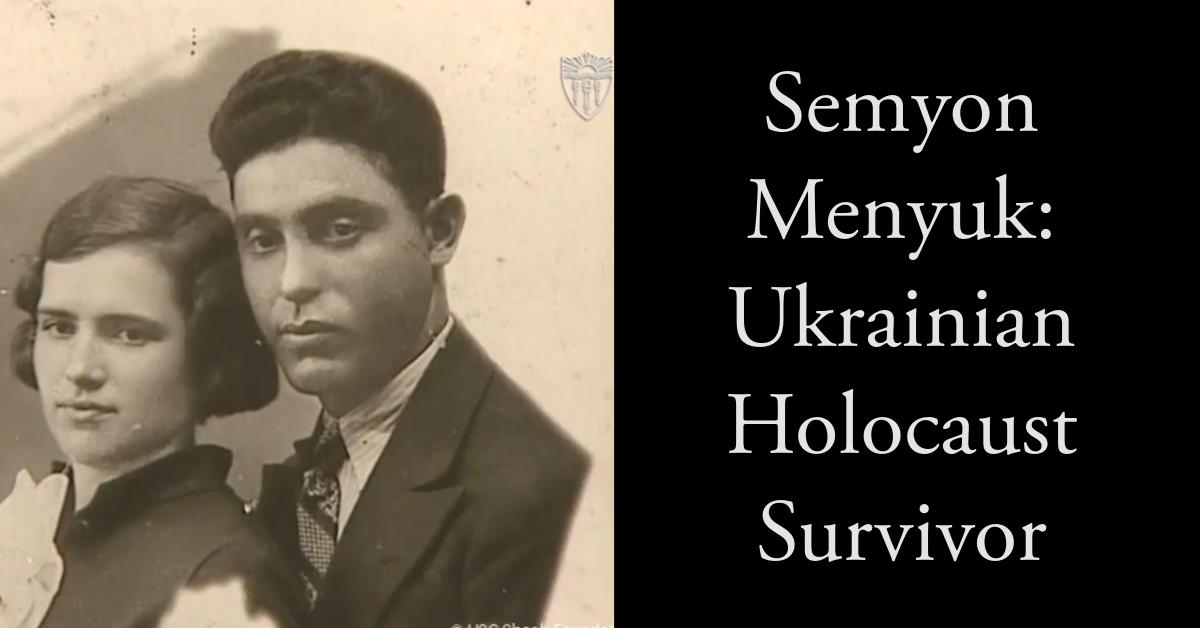

Semyon Menyuk: Ukrainian Holocaust Survivor

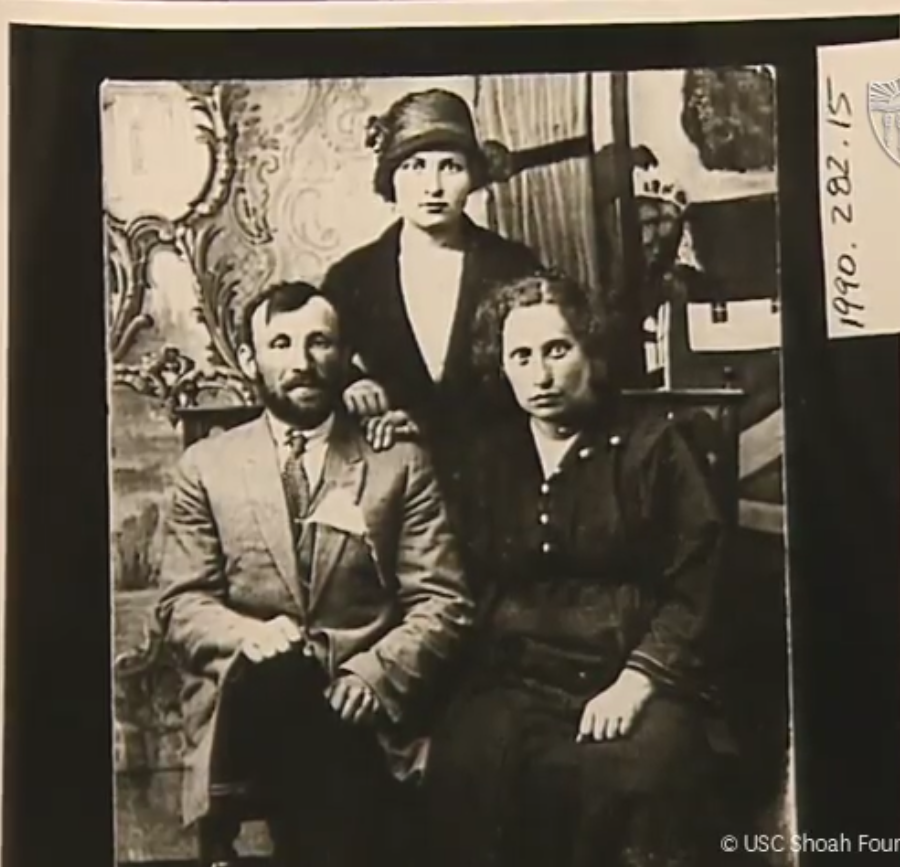

On Friday, May 12, 1922, Semyon Menyuk, also known as Yisroel Baruch, was born in Komorovo. Komorovo was a small village, housing approximately 250 families and only a handful of Jews. Semyon had not seen antisemitism until 1935, when the Polish people at school would fight with the Jews simply because of their Jewish identity. He finished school in 1938, and then he began to help his parents with their small farm. He helped his family until the war with Germany and Poland began in 1939. At this point, he began to do government business for universal stores. Business was good; however, Semyon was one of the youngest workers, so people would often laugh at him that he was working at a place with mostly older people. He continued to work until the war with Russia began. Semyon remembers vividly the day he stopped doing this business; he was planning to take money from Komorovo to the main office in Kolki but was advised against it. Some people knew where he was going because he always went at the same time, and they told him they saw some people with guns in the forest, so it was safer if he didn't go. Semyon heeded the words of the townspeople and decided to go home, and he didn't go back to work after that.

Little did the people of Komorovo know this was only the beginning, and it would soon worsen.

They thought about leaving, but they also felt like it was okay to stay because they didn't think the Germans would do anything to them; after all, the Germans were the nicest of people, especially to the Jews, so they didn't leave. They had heard about the Germans getting closer, and it was only approximately two weeks until they showed up in the town of Komorovo. One German man told his father that if he stayed, he would have a terrible time, and he was not sure if he would survive, but it was too late; they had already fallen prey. At this point, they decided to migrate to the forest to get more protection from the government. After staying a couple of days in the forest, they decided to go back home, and what they found was nothing like they would have imagined. "When we came back, the house was robbed; it was empty. The only thing left was the walls." Semyon recalls thinking back to that horrid day. Then, they went to live with his mother's sister, who also lived in Kamorovo.

The Ukrainians in the town were not any nicer than the Germans. The Ukrainians did terrible things to the Jews; at night, they would come and shoot near their houses. They took the men to the water at night and told them to go in, and one night, they came to him and asked him for his money. Every day, they made new problems for them. Then, to make matters even worse, the Germans said they were going to take them into the ghetto, and they were only allowed to bring food with them, so they all took the little food that they had. The ghetto that they went to was in Kolki. From what Semyon remembers, the ghetto was a horrible experience. The Jews in the ghetto were beaten and made to do all kinds of work. They worked on farms, cleaning horses and bathrooms. There was no food, and no one had any money to buy. "They put a piece of clothing that was yellow in the front and back to show you were Jewish," Semyon says, recalling the dark days in the ghetto. Every day got worse, and they gave up all of their clothes to try to get some food.

The worst time in the ghetto happened in 1942 when they made Jewish police called "Judenrat," who were told to bring the Germans gold and stuff or else they would kill them. The Judenrat came to the houses of the Jews and asked them for gold, telling them that if they didn't give it, things would only get worse, so the Jews had no choice but to give over their gold and prized possessions.

It came one day when the Germans took Semyon and his father to a warehouse with around 40 or 50 other men, and they locked them in for the night. They had no idea what was going on, and they thought this was the end; they were going to be killed. No one could sleep, having the unknown hung over their heads. In the morning, they opened the doors and told everyone to come with them, and they would show them what to do. They told everyone to go into the houses, and whatever they found, they should take and bring to the warehouse. On the way to the houses, they could see the streets of the ghetto lined with dead bodies. They came to the house where they lived and called out for the mother and sister, but no one answered. They went to the next house, and no one was there either; they were met with silence. The German police came to them, beat them, and told them to work faster. They told the Jews to take all the people who had been killed and put them in wagons, and they would show them where to put them. "The place is impossible to explain; it was horrible. Families were broken." Semyon recalls with sorrow.

They knew that something might happen again, so they refrained from sleeping in the ghetto. Instead, they decided to sleep on the farm where they worked, hidden away in the straw. In the morning, they didn't hear anything, so they came out and saw the Germans were there. The Germans said, "Jews, come out," so they came out. They beat his father, and they took them to the ghetto.

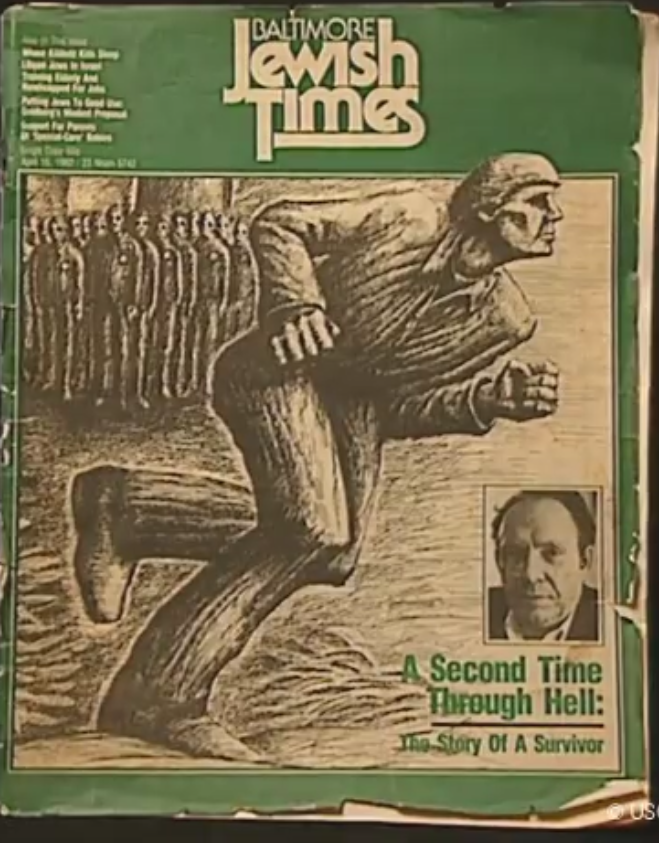

There was a Polish man who told Semyon that he had a pistol, so Semyon told his father that they should go together because they were going to be killed anyway. His father didn't want to go because he did not want his son to see him get killed, and he didn't want to see his son get killed, so he left the house they were in. Everyone in the house felt horrible; tears were shed nonstop. When the Germans came to the house, they took them outside, and they beat them. They put everyone on trucks, and it was hard to sit up because people were sitting on their feet. They took them to the ghetto to the forest, and again, they thought they were going to die because this is where they killed their families before. The Polish guy with the gun tried to shoot his gun, but it didn't work, and he was killed on the spot. Semyon doesn't know where he got the energy, but somehow, he managed to work up the energy to jump off the truck and begin to run. At this point, they were already killing people. One of the Ukrainians said to the policeman, "You see that one Jew is running," and he began to get shot at, but luckily, by some miracle, he did not get shot.

He ran until he came to a barn, where he went and got right into the straw to hide. It was then he noticed the blood coming from his nose, so he thought he had been shot and wounded. After a couple of minutes, the policeman went to the barn with the owner and said, "A Jew came into the barn." When they came on top to where the straw was, instead of uncovering Semyon, he began to cover him more with straw, not realizing he was under it. The confused police couldn't figure out where he was, so he went back down, and Semyon was relieved. He was in the barn, and he could hear the sounds from outside, the sounds of women and children crying. "I will never forget," those sounds lived with him the rest of his life. It was only a few minutes, but then it became quiet; they killed everybody. Unsure what to do, Semyon remained in the bark the rest of the night.

Semyon decided he wanted to go back to Komorovo, his birth town. However, if he went back to the ghetto, he would be seen by the police by the bridge. He decided he was going to find another way to get there. He grabbed a pitchfork, went out of the barn, and began to run. He went first to the highway and then the forest. He kept falling along his run but pushed himself to get back up because he needed to get to the next town before it was morning. While running, he passed by some men sitting around a fire in the forest. They were talking about what was going on in the ghetto, but he did not think these were people he could talk to, so he kept going. He made it to a village called Kulikowicze. He needed to get across the river to get to his town, but he needed to find a way. He began knocking on people's doors, hoping someone could help him. Unsurprisingly, many were afraid to open the door because it was nighttime, and all they could see was a man with a pitchfork. Luckily, one man told him he could find a boat close to the river, so he decided to check it out. He found the boat, but he had no oar to use to row the boat, so he had to think cleverly. One man told him he could check the barn for an oar, but he was afraid to go in because he was unsure what he would find, so he just stuck his hand in and pulled out some clothes. He put the clothes on the pitchfork and used it to row the boat because it was his only option. He managed to make it over the river and back into his hometown.

As soon as he arrived back in his village, he went to the house of a man whose son he used to be friends with. The man he went to was Ukrainian, as no more Jews were living in his town anymore. He told the man who he was and asked the man what he should do, but the man could offer him no place of refuge because he knew that if anyone found out he was hiding Semyon, they would both be killed. The man told him though that a Jewish man had gone to the forest to where the houses were. Having no choice, Semyon decided he would try to find this man.

Upon reaching the houses, Semyon asked the people if they knew where this man was, but their only answer was that he came to get food, but then he left, so they had no idea where he stayed. With no choice again, he continued into the forest, where he wandered. It was at this point that Semyon felt helpless and hopeless. For nights, he couldn't sleep, and he cried. "I felt no one could help me," Semyon says of the despair he felt those nights in the forest. He had lost all his family and had nowhere to go.

After two weeks of walking alone, he saw a man not too far away in the distance, and his instincts told him this man was a good person, so they came to one another. The relief that washed over Semyon was unreal; he recognized this man, this was Srulik, the man he had been looking for! They both told one another what had happened to them, sharing their stories detail for detail. After sharing their horror stories that were their real life, they had to decide what to do next. They were unsure what to eat, and the water they took was from the forest, so they had no idea what was in it; for all they knew, it could have caused them severe sickness. What made it even more challenging was that the Germans had made it clear that if they found out about anyone giving the Jews food, their fate would be death, so people stopped giving.

Life was terrible for them; there were a lot of lice, and there wasn't a part of their bodies that didn't have blood. The only word to describe such living conditions is unbearable.

It was winter, and the forest was freezing, so they needed to decide how to keep themselves warm. One man gave them advice to make something out of wood and hay so that they would stay warmer. Another man advised that they save their bodies by digging into the ground and making somewhere they could stay warmer than the surface. They took this man's advice, dug a hole in the ground, and covered it with wood so that no one could see inside. In the hole, it was warmer than outside, saving them from freezing. While it kept them from freezing, the winter was brutal. They were still freezing and couldn't light a fire because they needed to be inconspicuous. Times were bad for both these men; Semyon describes it as "We didn't shave, we didn't cut our hair, it was like animals."

They stayed in the hole until the underground water began coming up, and then they knew it was time to leave. It wasn't freezing at this point, and they could stay in the forest without the underground shelter. This time was no good either; they were constantly on the hunt for food and a place to sleep, and when they arose in the morning, they were on the run. On top of the terrible conditions they already had, the Ukrainians wanted to kill anyone who wasn't Ukrainian, so they were fighting for their lives from all sides. To the left, the Germans; to the right, the police, and from all around, the Ukrainians. Their paths were painted in blood.

Finally, some luck was bestowed on them. They had asked some Polish guys what to do and took them to a place in the forest near Manevytskyl. The people took them into a house in the forest, and they gave them clothes, and they were able to shave again. For the first time in a while, they felt human again! The happiness they felt was unreal.

After this, they met a group of Partisans to whom they disclosed their Jewish identity, and they told them they wanted to go with them. They went with them to another village, where they got food and met other Jews. It was the first time in a while they had seen other Jews, so that they couldn't be happier. They told them they'd be there for a week, so Semyon and the others began to help them. The Partisans gave them guns and taught them how to use them. They took them to the main office in the forest, where Semyon met his cousins. They went to the railroads and began blowing them up. The Partisans had one goal in mind: revenge.

There was a group called Kruk, and they were the Jewish partisans. Life with the partisans was much easier than Semyon's life before. They were told they would fight Germany from behind; however, a river was blocking them from fighting from behind. They waited a few days and then decided to send them into the Russian army. The Russian military taught them how to fight and spy on the Germans. Many of the people they sent out didn't make it back, or they did, but only a few remained. "You couldn't say you didn't want to do it because you know what had to be done," Semyon says, recalling his time with the Russian army.

At one of the jobs that Semyon was sent to do, he was wounded in his foot. He was transferred between 6 or 7 hospitals, where he stayed for about 6-7 months. They wanted to cut off his foot, but some people told him that he shouldn't let them do that because, in a few weeks, he'd be better, so he heeded their advice. He stayed in the hospital until 1945, when he was let out on crutches. They gave him some rubles when he left the hospital, but he didn't know where to go.

Semyon went to Kovell, where he met a Ukrainian guy whom he told about his predicament of not knowing what to do or where to go. The man was very nice and said to Semyon that he could come to his house and stay with him. They took him in as if he were their son. They told him they would help him get married. He stayed there for a couple of weeks.

He had met a woman in the hospital who was working there during his time, and she told him he could go stay with her sister in Kyiv, so that's off to Kyiv he went. This woman told him she had a girl for him to meet, and little did he know that girl would become his wife. He met his wife Mina in Kyiv, and they married shortly after that. For a while, he lived in Kyiv with his wife and the son Michael, to whom his wife gave birth in 1946. However, life in Kyiv was not good for them, and they didn't have much food to eat. He told his wife it was time for them to leave and go to Kolki, so 1947 they moved there. In Kolki, he began working as a warehouse and restaurant director. During this time, his wife had two other children: another boy whom they named Yaakov Yasha and then a girl named Fiona. After some time, they wanted to go back to Kyiv, and they did, but it was not easy to move.

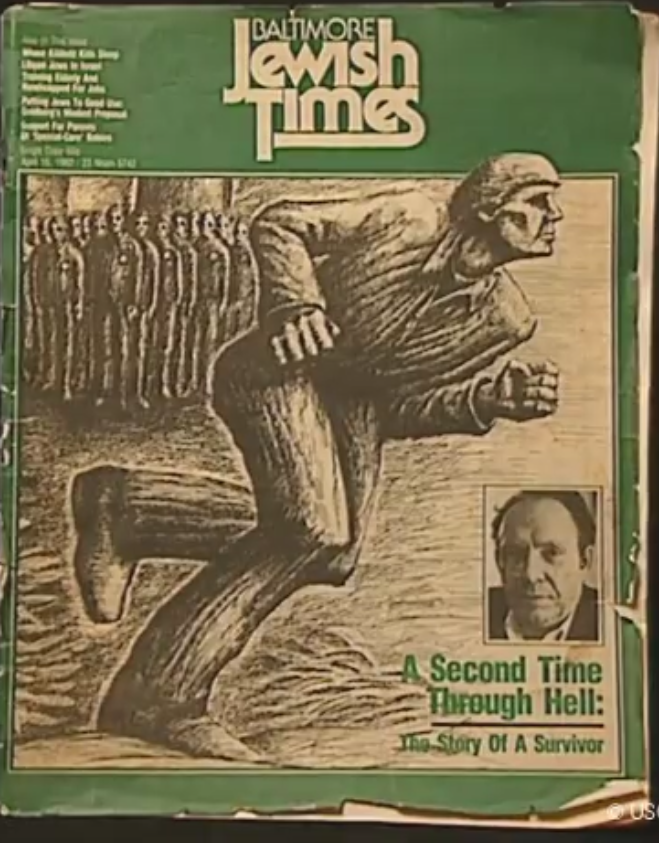

In 1973, one of Semyon's cousins in Canada sent him an invitation to come to Canada for a few weeks. After visiting his cousin in Canada, Semyon realized he liked Canada's life and wanted to move there, but then came a bad time in Russia. The Russians began accusing him and his sons of being spies for America and Israel. They told him he was going to take his sons and fight in the Israeli army against them. Semyon wanted to leave, but they were giving him a hard time. They even threatened to put him in jail! Finally, they told him to write on a paper that he was guilty, and then they would give him a card and send him out of Russia, which is exactly what he did. Just like they had promised, the following day, Semyon received a card to get out of Russia. Although he wanted to go to Canada, they couldn't for some reason, so they went to Washington instead because he had cousins there, too. In 1977, Semyon and his family finally made it to America.

Semyon's upbringing was one that most cannot fathom, from being a part of the Holocaust to losing his entire family. The strength he possessed to get him through the most challenging of times is something to be admired. Semyon wanted to thank all the organizations that have brought light to the horror that was the Holocaust. He was thankful there were people out there spreading the message of what happened to him and the other Jews during such difficult times. It was essential to Semyon that the story of the Holocaust never be forgotten because as more time goes on the less and less witnesses there are and the further away the Holocaust seems to be. While Semyon passed away in 2009, his message rings loud and clear: we must never forget what happened to the Jews.

Reference:

https://sfiaccess.usc.edu/Testimonies/ViewTestimony.aspx?RequestID=35e097f4-e01e-4883-b7bb-3793976bb05b

~Blog Written By Avigail Meyers