Story Summary:

October 22, 1941, was the day that would change Ignac's life forever, although he did not know that at the time. This day would mark the transition from home to the labor camps. No one would have imagined this would be the start of 48 months of intense labor and harsh conditions that no human should ever endure. He recalls the yellow bands the Jews had to wear to show they were Jewish.

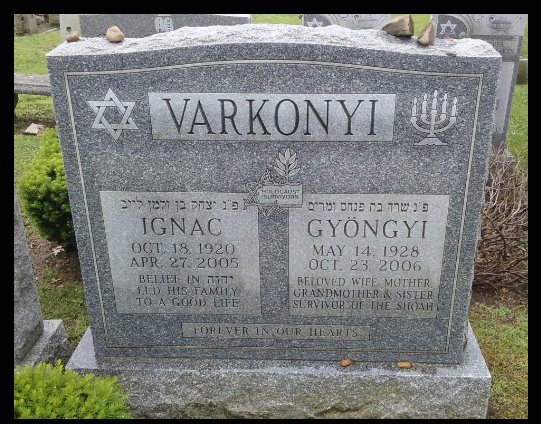

Ignac Varkonyi: Hungarian Holocaust Survivor

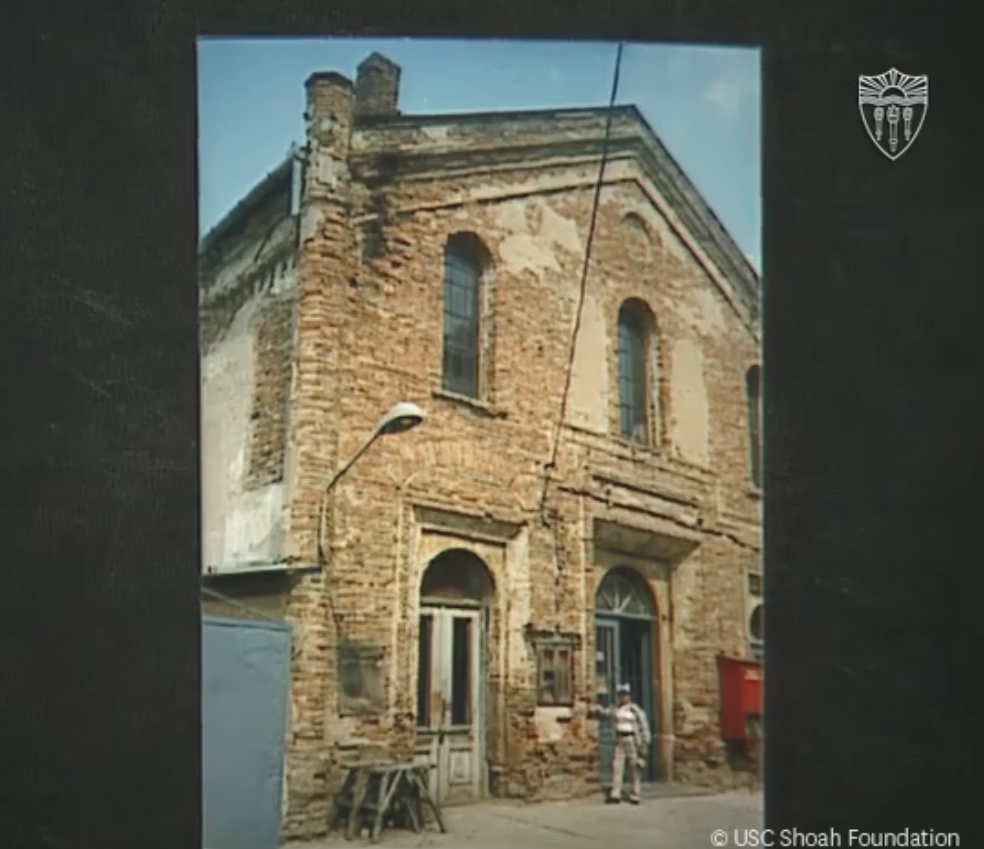

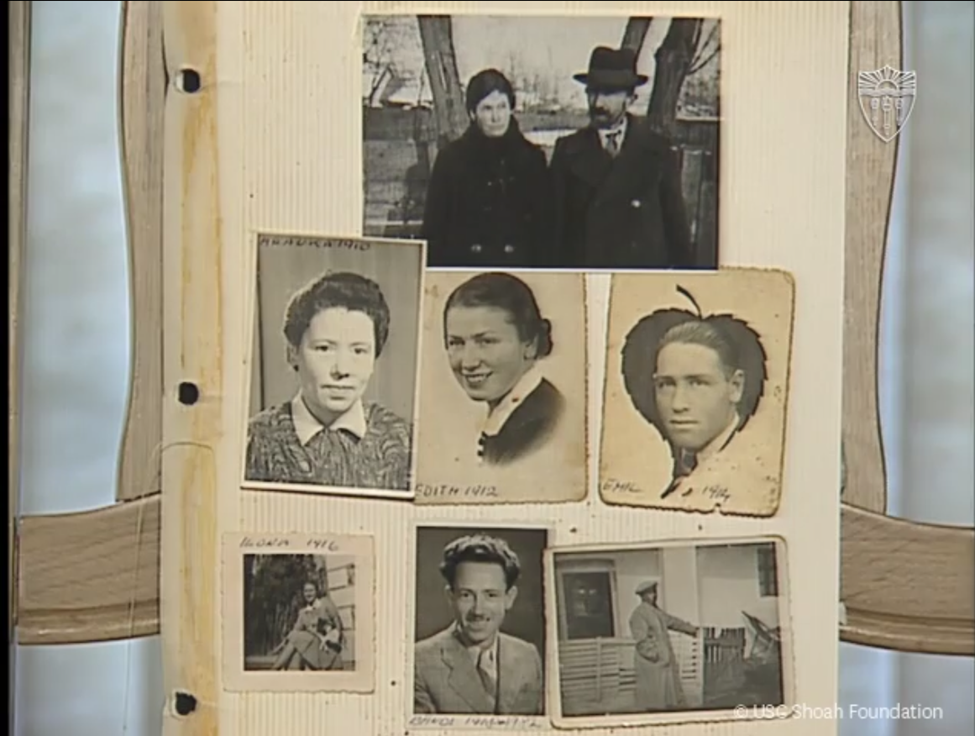

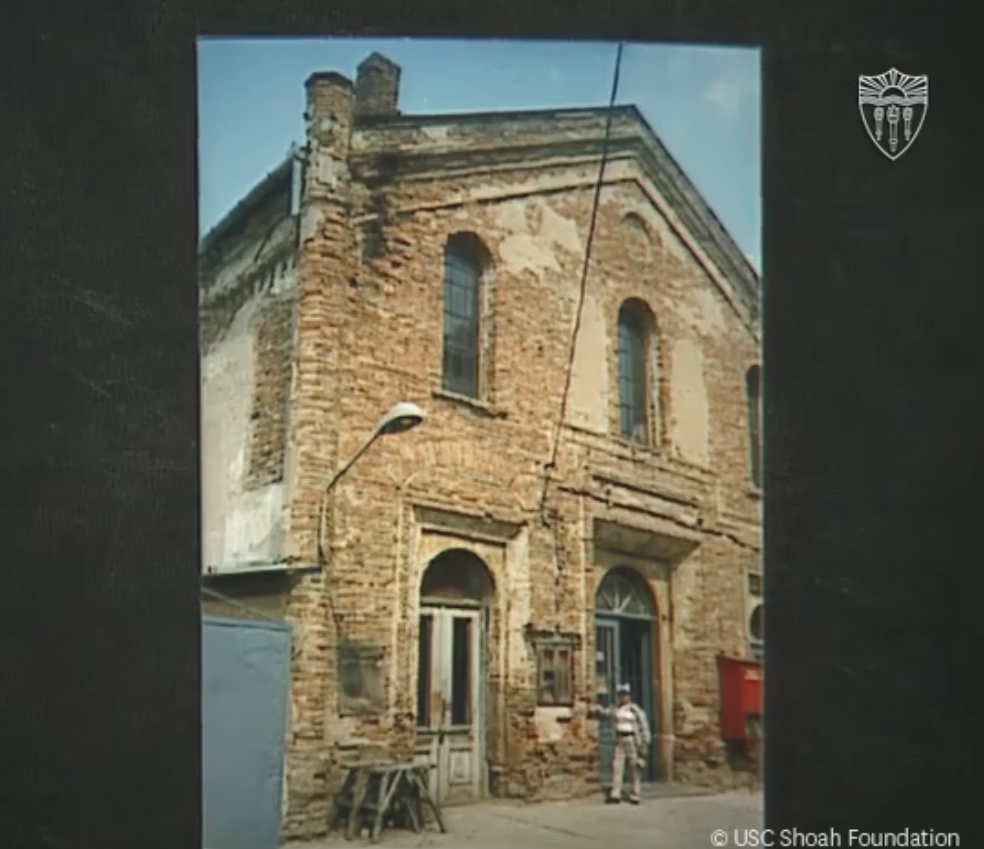

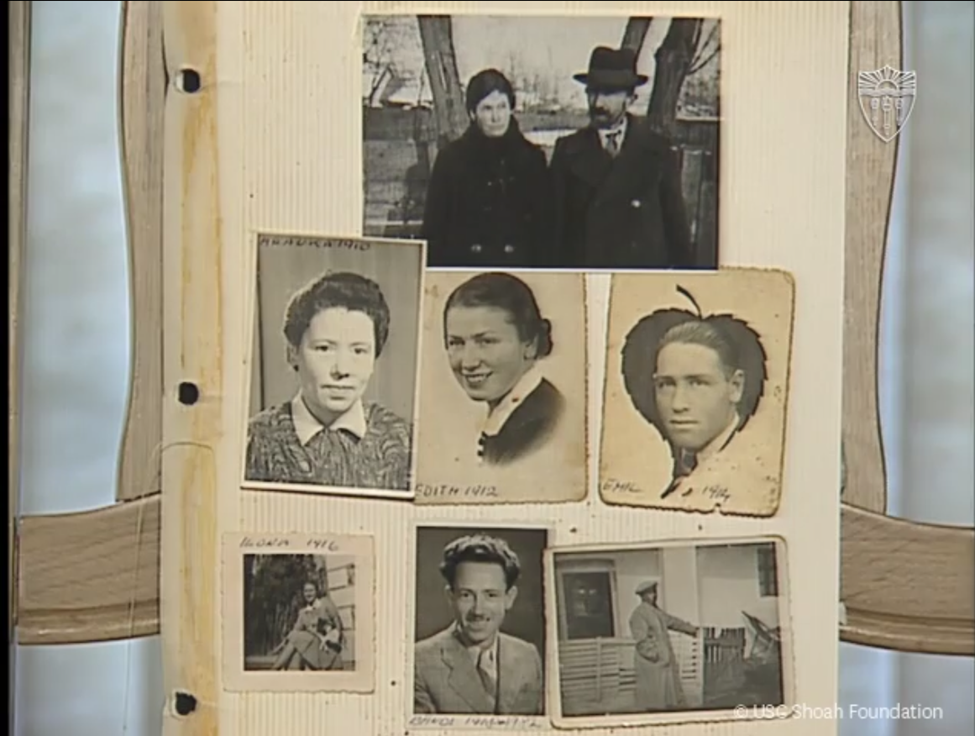

Ignac Varkonyi was born Monday, October 18, 1920, in the town of Hajdúböszörmény located in Hungary. He was the youngest child born into a family of six, with two brothers and three sisters. The town of Hajdúböszörmény was no friend of the Jews, for all the inhabitants were no strangers to antisemitism. Ignac recalls the non-Jewish boys at school trying to fight with him simply because he was a Jew. Even before the Holocaust, those living in Hungary felt hatred and resentment from the Gentiles around them.

October 22, 1941, was the day that would change Ignac’s life forever, although he did not know that at the time. This day would mark the transition from home to the labor camps. No one would have imagined this would be the start of 48 months of intense labor and harsh conditions that no human should ever endure. He recalls the yellow bands the Jews had to wear to show they were Jewish.

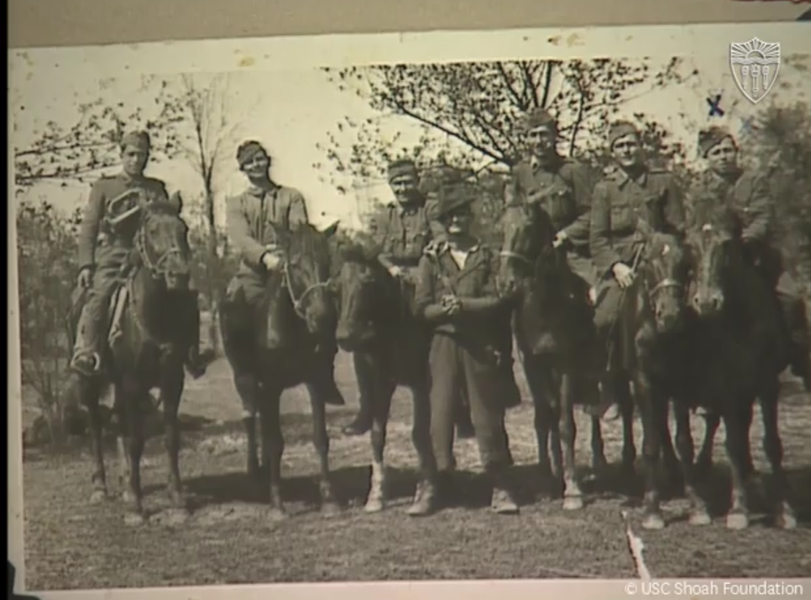

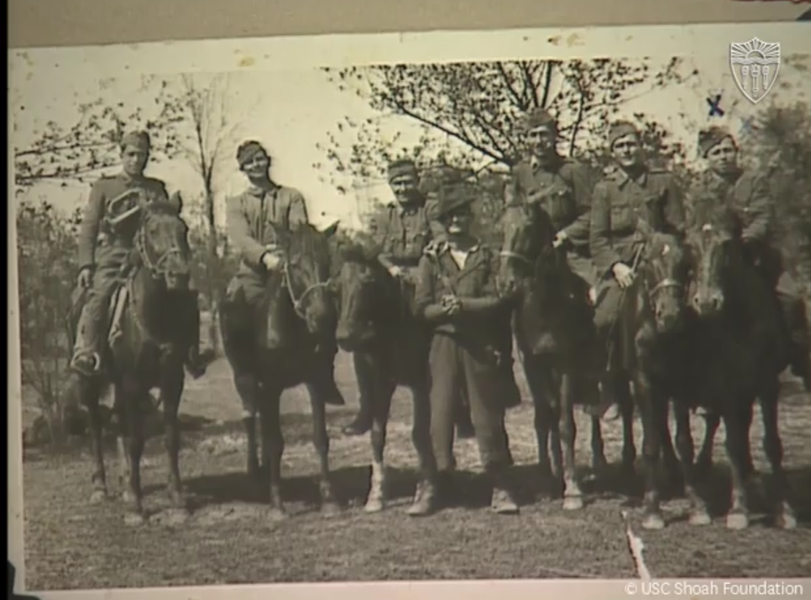

Upon entry into the labor camps, the Jews did not know what to expect, for they thought they were working; however, it was much worse than anyone let on. The labor camps were nothing short of their name, as the Nazis in these camps made the Jews work very hard. Most of the time, the work that they gave the Jews was the same work, such as building airports, unloading from trains, building roads, and sometimes loading food and ammunition for the army. The work they gave the Jews was the work they did not want to do. When they weren’t giving the Jews this dirty work, they would give them impossible tasks such as pulling horses with hundreds of pounds on them. He vividly remembers that they did not get any lunch if they did not do the jobs. He said, “The main punishment was not getting food three times a day but only once.”

Ignac was in five different labor camps; two were barracks, and the rest were not. From the time he stepped foot into the first labor camp until the last one, they were always on the March. The March consisted of hours and hours of walking from one camp to another with no breaks and no pity for those who could not keep up. While going from one camp to another, Ignac met his brother accidentally on the way; however, they fell prey to the gunshots of the people around them. To their luck, an officer named Kent wanted to save them, so he ensured they were given jobs so they were not killed. Although he was still with his brother, the two decided to separate so that if one of them died, the other would live.

The labor camp that Ignac went to after he left his brother was called Mauthausen. This camp was located in Austria, the biggest camp they had there, with 60,000 people. As usual, to get to Mauthausen, the Jews continued the death march, and as Ignac recalls, it started on Feb 1994 and ended in Sept or Oct 1994. The March began with around 300 people, but upon arrival at the camp, only seven remained alive, Ignac being one of them. As expected, those that were in this camp were in terrible condition. Many wanted to escape; however, they feared for their lives because they had signs all over the town stating that if anyone saw someone who ran away, they needed to turn them in. It was known that if they were turned in, the police would immediately shoot them. According to Varkonyi, some people managed to escape but never returned, so he had no idea of their fate. Ignac was lucky to be a baker because he was taken to the bakery, which helped him; unfortunately, others were not as lucky. If a person had something to offer to the Germans, they had more chance of surviving; if not, they ran the risk of being eliminated at any point.

While Ignac was in these camps, the only way he knew what was going on with anyone else in his family was through the letters they had sent him. His family had sent him letters informing him that they had been taken to the ghetto, so he knew they were also enduring some labor camp. The last letter he received from his family was from his mother, who was in Auschwitz when she wrote it.

Upon leaving Mauthausen, they continued to march; however, the Russian army was a threat this time. Ignac says, “There was a time when the Russian army was so close, about 20 miles, and we even heard the cannons being fired.” At this time, the officer with them told them they were going to hide on a farm so that the Russian army would not find them. They had to hide from the Russians and the Germans, so they had to be careful that no one would see them. To put their minds at ease due to their fear of being caught by the Germans, the people at this farm went into a wine cellar to hide. The farmers on this farm were very welcoming to the Jews and even gave them food and clothes. As people coming from the labor camps where they barely had even the bare bones, this was a treat. They stayed in the wine cellar for three weeks before they continued on their way. After this, they were given back to the German army, and they were all separated.

Shortly after they were back in the hands of the Germans, they were liberated by the Russian army on April 26, 1945. At the time of liberation, the Jews did not know what was happening. Many of the people in the camp were sick and had very low weight because of the lack of food they had. Unfortunately, because many people were malnourished when they were given food, they ate it too quickly or overate, which caused many of them to die shortly after eating.

Upon returning home, Ignac learned that all of his siblings, aside from one of his brothers who was home, were scattered in different places in the world. Although his siblings survived the Holocaust, his parents did not have that same fate, for they had perished in Auschwitz.

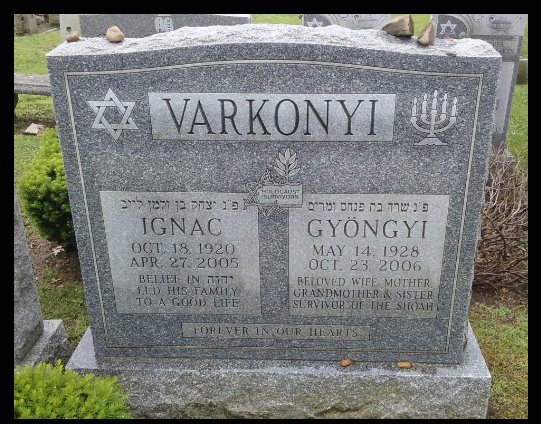

After the war, antisemitism still ran thick in Hungary, and it was not an easy place to secure a job as a Jew. For this reason, Ignac changed his family name from Weiss to Varkonyi so that his last name would not identify him as a Jewish man. At this time, it was also very challenging to find a Jewish woman to marry, as most Jewish women were killed in concentration camps. Ignac persisted and would not take no for an answer from the Jewish woman he set his eyes on, no matter the challenge. After three years, in 1950, Ignac married his wife Gyongyi, and 1951 they had a son.

With continued hate towards the Jews, Hungary was no longer a suitable place to reside or raise a child. This led them to take the leap to move out of Hungary and into Brooklyn, New York. In New York, Ignac opened a bakery and continued to use his skill as a baker to provide for his family. It was also in New York that he was blessed with another child, a daughter. In 1982, Ignac did not want to work anymore, and he retired along with his bakery. He spent the rest of his life with his family and eventually began telling his story of the horrors he went through in the Holocaust. On April 21, 2005, at 84, Ignac was laid to rest.

Through all the hardships Igac went through in the Holocaust and the hatred he faced being a Jew, he was determined to continue his Jewish bloodline. He continued to persist in the most challenging times, which is something to be admired. Ignac may not be around anymore, but he forever lives in the hearts of his family members.

~Blog Written by Avigail Meyers

References:

https://sfiaccess.usc.edu/Testimonies/ViewTestimony.aspx?RequestID=1c613807-bd52-42f0-b4a9-467c0af1e58a