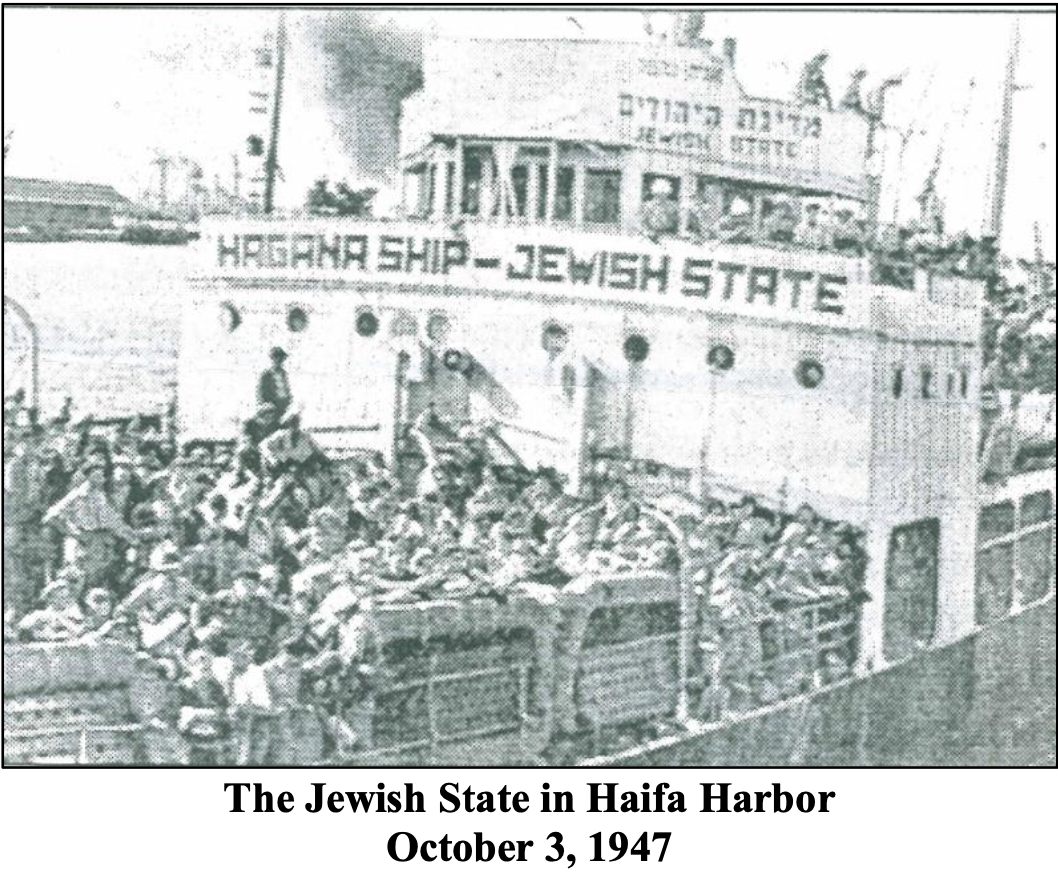

Ship: USS Northland ("The Jewish State", "Medinat Yehudim" in Hebrew)

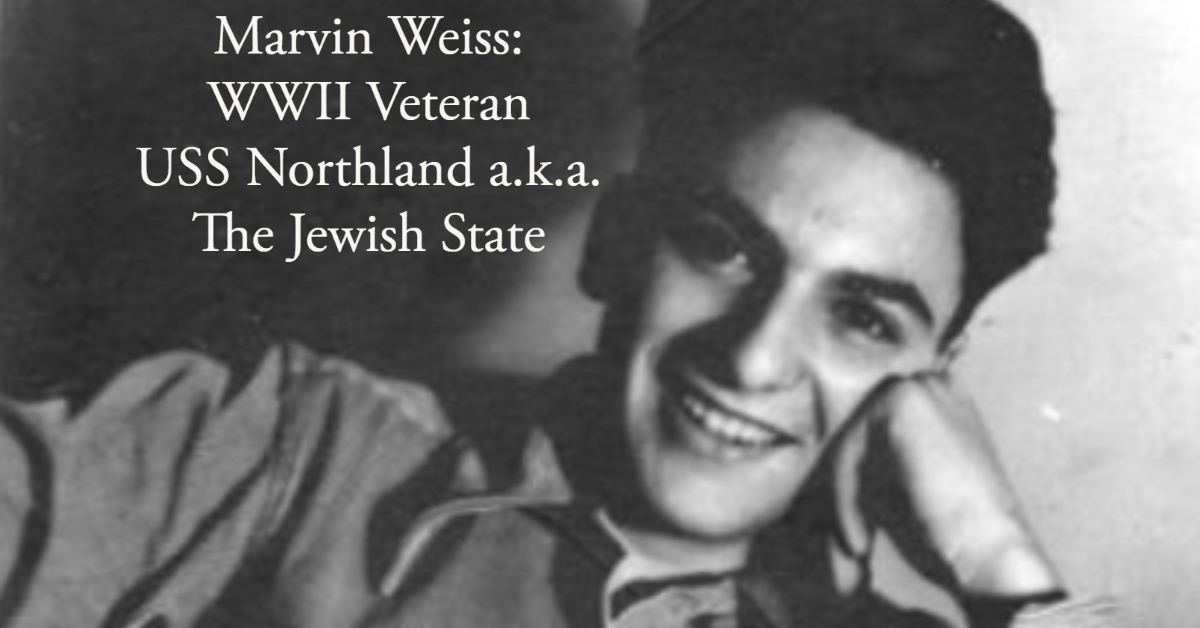

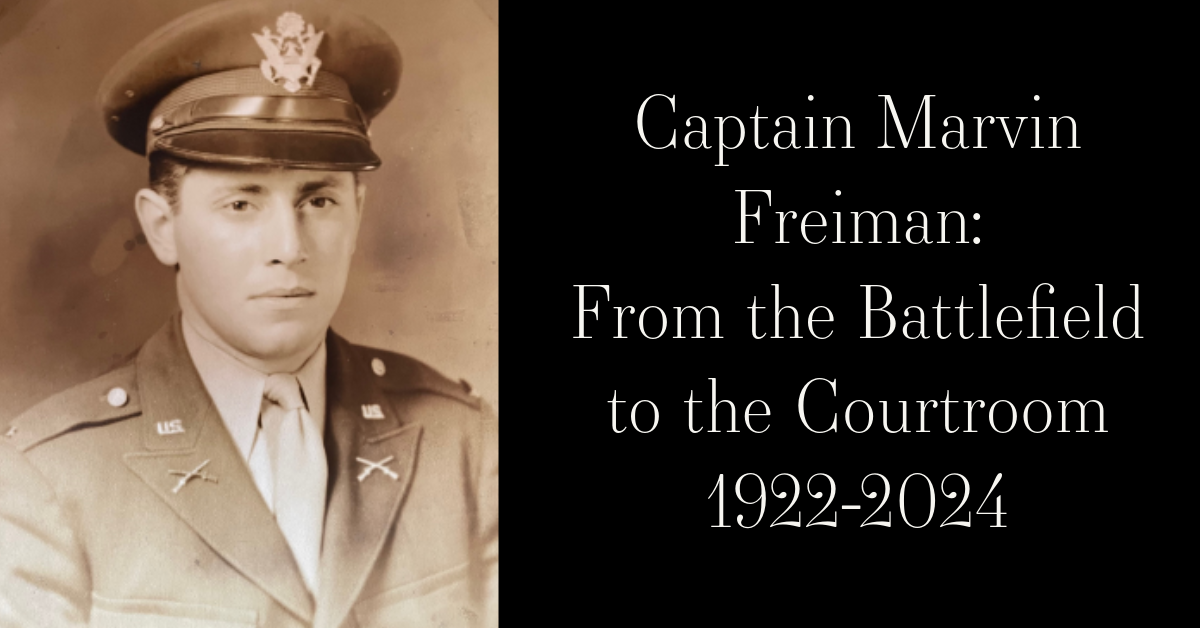

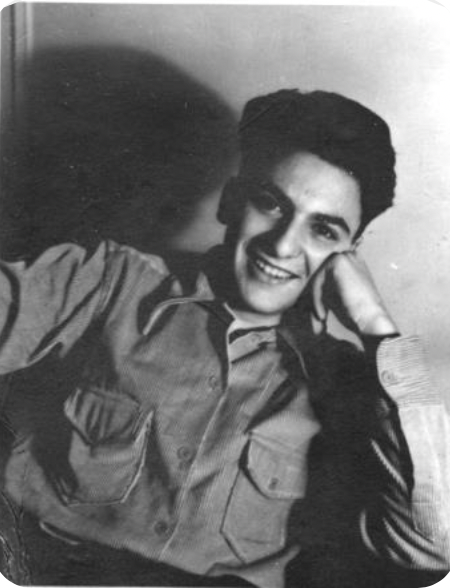

Many times, when we seek to unravel the stories of an individual’s past, we are left picking through small bits of information, a date here, a location there. Rarely are we so fortunate to be handed a detailed account of a life written by the very individual who lived it. Marvin Weiss was a diligent man who sought exploration in both the physical world and the mental. Beginning as the son of Jewish Romanian immigrants in Bronx, New York, Marvin invented a life for himself that took him around the globe, aiding lives both directly and indirectly. As an engineer, he viewed the world as pieces to a puzzle. This story, though only a brief glimpse into his life, shall pull directly from his own words as much as possible.

Marvin’s time in the Navy was short, serving for only two years. Upon leaving service he set his eyes on engineering school but “there were millions of GIs with the same idea, and I could not get in. After a year of trying, I decided to wait and try again later. I volunteered to work on a refugee ship that would try to break the British blockade that was preventing Jewish refugees of the holocaust from getting into Palestine.”

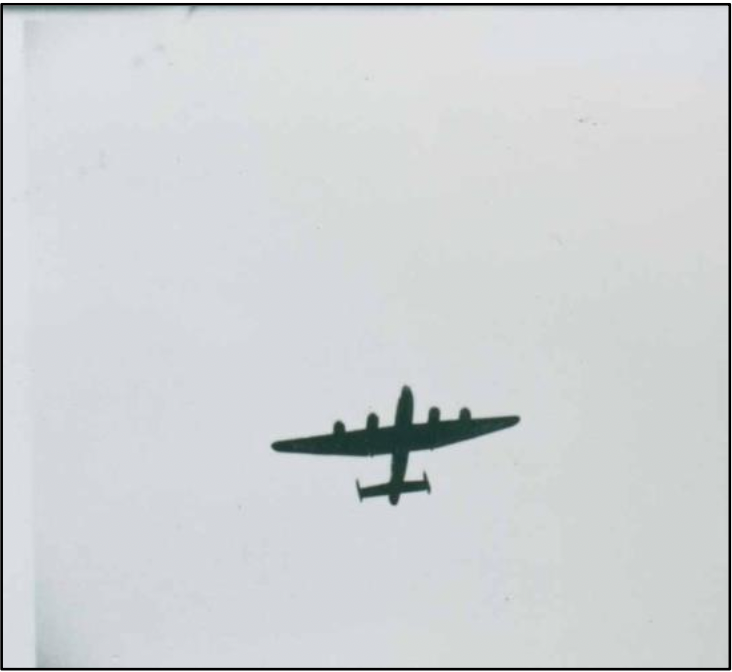

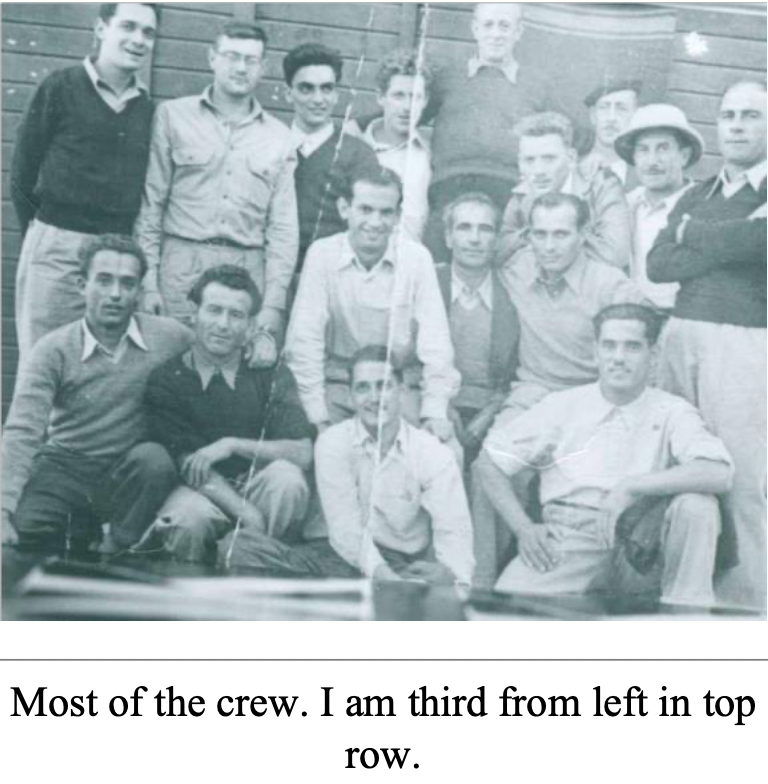

“This is the story of my trip on the USS Northland, a Coast Guard icebreaker, later renamed ‘The Jewish State’, ‘Medinat Yehudim’ in Hebrew. I was classified as an electrician because of my navy training so from their point of view they had covered that base. I was in charge of everything electrical on the ship. The rest of the crew was equally sparse. The main problem was the diesel engines that kept on blowing their cylinder head gaskets. Fortunately, we had enough spare parts and didn't run out of gaskets. The Coast Guard must have known about the problem otherwise why would we have had dozens of the copper gaskets aboard?”

The Medinat Yehudim set sail across the Atlantic. That first step in the journey came with trials but “by the time we entered the Mediterranean Sea we were an experienced crew.” At a port in Marseilles, France, the crew looked forward to bit of reprieve but within a few hours the British had discovered their intentions and it was time to go.

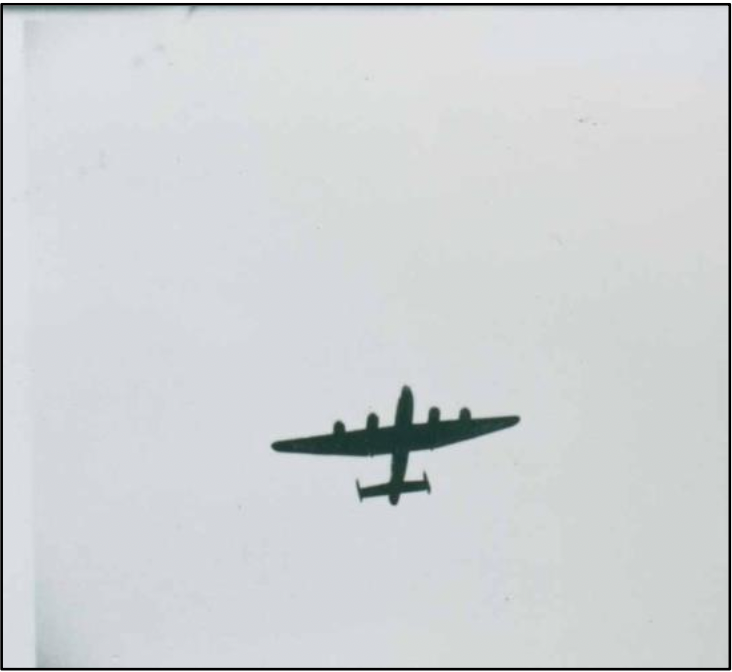

“So out we went into the Mediterranean, heading back to the Atlantic. Where were we going? They would not tell us. Security was tight. Only the Israelis were in on the secrets. But while we were in the Mediterranean, a British destroyer shadowed us, or a British airplane hovered over us.” They managed to find refuge in Bayonne and for three months prepared the ship for passengers. “How do you get over 2,600 passengers on a little ship like the Northland? Every available space below deck; holds, storerooms, etc., were fitted with wooden shelves, six feet deep and three feet apart. Every passenger was allotted an 18-inch space on a shelf for him or her and all their baggage.”

“At the end of the summer in 1947 we sailed out of Bayonne and reentered the Mediterranean. We stopped at no ports and sailed directly to the Dardanelles and into the Black Sea. Things happened rapidly after that. We docked in a Bulgarian port named Burgas and were not allowed to go ashore. That evening the passengers started to arrive by bus and truck. Our passengers had survived the holocaust in Siberia. They were mostly Eastern European Jews who had managed to escape the invading German armies as they swept west. There appeared to be a lot of intact families, but it turned out later that most of these families were not the original ones. Most of the survivors were individuals who had formed into new families while in Siberia.”

“Packing them down into the ship into their wooden shelves took place in the dark of night as rapidly as possible. It must have been a traumatic experience for them, but they had been prepared for it and were quite cooperative. The operation went smoothly, and we sailed the next morning September 26, 1947.”

“The trip to Palestine took seven days.” The crew and passangers were fortunate enough to have a smooth journey. “Those of us that spoke Yiddish were able to ‘join’ a family and become ‘members’ of it. We were encouraged to do this. I had a nice intact family with a husband, a wife, two small kids and a teenage girl. When I had time for them, I enjoyed their company. In the turmoil later and because of my illness I lost contact with them and never was able to recover it.”

“In addition to this family, I had a wonderful boy of about 11 that attached himself to me and followed me around wherever I was, helping me as best he could. He had a great deal of energy and was a perfect little gentleman. I lost contact with him also and it is my great regret that I don't know what happened to him. He was very talented, and I am sure he was successful in life.”

“When we reached the shores of Palestine there were six destroyers waiting for us, one of which one had a big drawbridge intended for boarding. There ensued a six-hour game of tag during which we zigged and zagged leading them on a merry chase. We were much more maneuverable than they. They did not want to ram us but in the course of the rumpus we did ram one of them making a small hole in the side of one of the destroyers. Fortunately, the sea was unusually calm, and the hole was above the waterline, so the ship did not sink. There was some tear gas thrown but no gunfire. It was the practice of the Haganah refugee ships to carry no arms of any kind. So, it was a kind of impasse.”

“Unfortunately, I only saw the beginning of the chase. After we had been dodging about half an hour, I got an emergency call about a problem with the steering engine that operated the rudder. The motor was smoking and extremely hot. I took a look and yes, the constant turning back and forth was overheating the motor. What to do?”

“There was a mechanism for turning the rudder by hand, but it took two strong men to do it and was slow and difficult. We needed to set up a way to communicate from the bridge to the room in the bottom of the boat where the steering engine was. I made an emergency announcement asking for volunteers and would you believe, I got a dozen men all of whom claimed to be electrical engineers. I deployed six of them to constitute a human telephone line to yell instructions from the bridge. All they had to yell was ‘rechts’, right, or ‘links’ left. The rest of them I detailed to keep putting wet towels on the hot motor and keep a fan blowing on it. It turned out that the motor did not burn out and lasted the whole time of the rat race.”

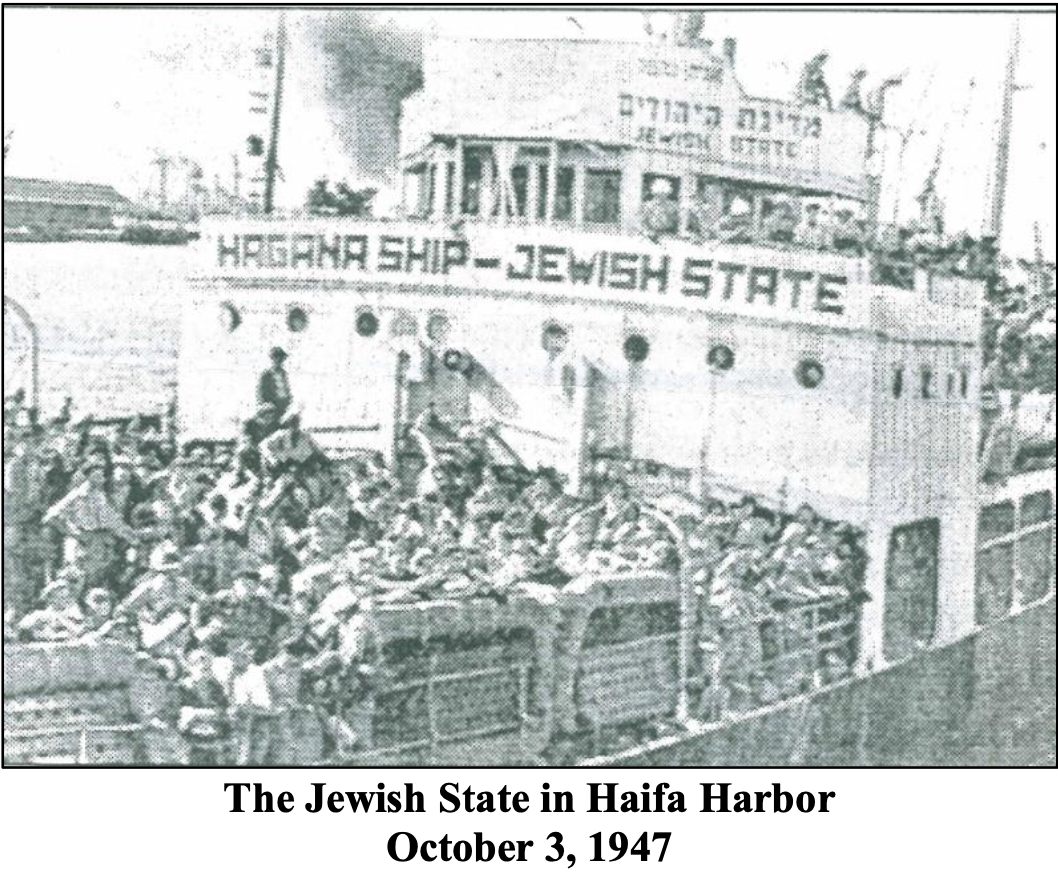

“Eventually the British did succeed in boarding us. There was very little violence. When they were fanning out to every part of the ship, we managed to remove all the control handles from everything and throw them overboard so that the British could not operate the ship. They had to attach a cable to us and tow us into Haifa harbor. The crew all dispersed among the passengers and became anonymous. Those of us that knew Yiddish had an easy time. The others relied on being silent. The British did not identify any of the crew.”

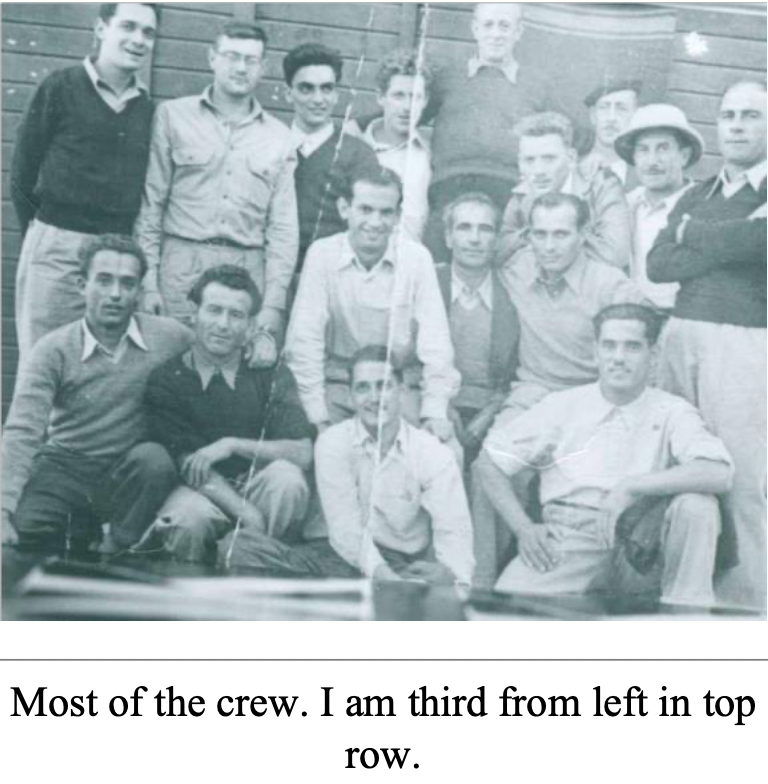

You can see the British soldiers on the bridge with their white helmets. I am somewhere in this picture.

“There we were, parked at a dock in Haifa harbor under guard. The British were prepared for us. They had a passenger ship ready to take us to Cyprus, to the detention camps. The British sent some bundles of food on board, mostly bread, and some containers of drinking water and announced that we would be transferred to Cyprus the next day.”

“The next morning there was a gangplank to the dock ready for us to disembark and get onto the passenger ship. When it came my turn, I had a funny feeling that the British watching me walk down the gangplank would be able to see by the way that I walked that I was an American. Nonsense of course. But that’s what I thought and to disguise myself I tried to walk in a heavy exaggerated tread that I thought looked like the walk of a Hungarian peasant. The British soldiers seeing me walk that way called out ‘Hey Tarzan’. I had a terrible time holding back from laughing and not letting on that I understood.”

Marvin’s time on the border of Palestine started off with baseball games and friendly gatherings, filling the time till they could enter. Marvin missed the first contigent into Palestine due to illness and within a month of entering, the region erupted in war, the Israeli War of Independence.

The remainder of his time in the region was a struggle between trying to navigate the chaos and his own personal suffering from sickness. Marvin would join in the fray, meet distant relatives, and pave a life that inspired him to write a memoir. Eventually Marvin made it back to the United States where he delved deep into engineering, patenting a plethora of inventions. Where most people live one life, Marvin lived multiple, all of which he chosAe to share with the lives he valued most as reflected in his memoir, “Dedicated to my grandchildren, Avery, Danielle, Marlena, Rachel, and Zachary who like my stories.”

May his memory be a blessing to all those whose lives he has touched.

~Story Contributed by the Weiss Family

~Blog Written by Michael Ackermann